Now that peace has come to South Sudan

By Paul Ejime

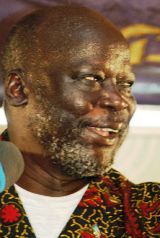

DAKAR, Senegal, July 11, 2005 (PANA) — Ex-rebel leader Colonel John

Garang’s joining of the Khartoum government as Vice-

President Saturday under a historic peace deal that

ended two decades of civil war in the south of Africa’s

largest country, opens a new vista in Sudan’s chequered

political history.

For a people who have suffered economic want and

For a people who have suffered economic want and

severe shortage of the world’s major common trading

currencies, the war-ravaged region, measuring about

650,000 square kilometres could be poised for its

brightest economic era yet, depending on what the key

actors make of the comprehensive peace agreement

Like most African countries, Sudan boasts numerous

ethnic groups. But unlike most States, it has had two

distinct divisions: the north, which is largely Arab

and Muslim, and the south, of predominantly black

Nilotic peoples, some of whom are adherents of

indigenous faiths while others are Christians.

Another unique historical feature is that Sudan was

ruled by Britain and Khartoum’s Arab neighbour under

the Anglo-Egyptian condominium of 1899-1955.

Britain finally signed a self-determination agreement

with Sudan in 1952, followed by the Anglo-Egyptian

accord in 1953 that set up a three-year transition

period to self-government, paving the way for Sudan

to proclaim its independence 1 January 1956.

But this was to be followed by two short-lived

civilian coalition governments before a coup in

November 1958 brought in a military regime under

Ibrahim Abbud that governed through the Supreme

Council of the Armed Forces.

Abbud’s government was accused of trying to Arabise

the south, and in 1964 expelled all western

missionaries from the country.

Northern repression of the south led to open civil

war in the mid-1960s and the emergence of various

southern resistance groups, the most powerful of

which was the Anya Nya guerrillas, who sought

autonomy.

Civilian rule returned to Sudan between 1964 and

1969, and political parties reappeared and in the

1965 elections, Muhammad Ahmad Mahjub became Prime

Minister, succeeded in June 1966 by Sadiq al Mahdi.

In the 1968 elections, however, no party had a clear

majority, and a coalition government took office

under Mahjub as Prime minister.

In May 1969, the Free Officers’ Movement led by

Jaafar Nimeiri staged a coup and set up the

Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). In July 1971, a

short-lived pro-communist military coup occurred, but

Nimeiri quickly regained control, and was elected to

a six-year term as president, abolishing the RCC.

Meanwhile in the south, Joseph Lagu, a Christian, had

united several opposition elements under the Southern

Sudan Liberation Movement and in March 1972, the

southern resistance movement concluded an agreement

with the Nimeiri regime at Addis Ababa, and a

ceasefire followed.

A Constituent Assembly was created in August 1972 to

draft a constitution at a time when the growing

opposition to military rule was reflected in strikes

and student unrest.

But despite this dissent, Nimeiri was re-elected for

another six-year term in 1977.

His abolition of the Southern Regional Assembly in

June 1983, gave birth to the Sudan People’s

Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Sudan People’s

Liberation Army (SPLA).

Garang used the two movements, which later merged

into SPLA/M, to launch his separatist rebellion that

saw him moving to the south from Khartoum.

Following his imposition of Muslim Sharia law

throughout the country, Nimeiri was toppled in a

military coup led by Lieutenant General Abd ar Rahman

Siwar adh Dhahab in 1985.

In March 1986, the government and the SPLM called for

a Sudan free from “discrimination and disparity” and

the repeal of the Sharia code.

Sadiq al Mahdi formed what proved to be a weak

coalition government following the April 1986

elections, but his failure to end the civil war in

the south or improve the economic and famine

situations led to his overthrow in June 1989 by then

Colonel Omar Hassan Ahmad al Bashir, the incumbent

president, who later took on the rank of army

general.

Twenty-one years of the bloody war between the

Khartoum government and the separatists in the south

killed at least 1.5 million people, and left the

region in ruins.

The protracted peace process were initiated by

regional member States of the then Inter-Governmental

Authority on Drought and Development (IGADD) during

their summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 1994 (the

group later changed its name to the Inter-

Governmental Authority on Development, IGAD).

On 20 May 1994, the Khartoum government and the

SPLM/A signed the Declaration of Principles (DoP) as

a framework of negotiations, which identified the key

issues in the conflict as:

Right to self-determination for the south Sudan,

separation of state and religion, system of

governance during an interim period, sharing of

resources, and security arrangements.

IGAD later appointed special envoys from Ethiopia,

Eritrea and Uganda with Kenya as the chair on the

tottering peace negotiations and a secretariat for

the IGAD Peace Process was then set up in Nairobi,

Kenya.

Later representatives from Italy, Norway, UK, US, the

African Union (AU) and UN joined in the process as

observers with Sudan’s first-vice president Ali Osman

Taha, leading the government’s team, while Garang led

the SPLM/A delegation.

It was only on 26 May 2004 that the parties reached

agreements on the substantive issues of the conflict

and solution clustered under the IGAD six protocols.

These included the Agreement on Security

Arrangements, Wealth Sharing, Power Sharing, Conflict

areas of Southern Kordofan/Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile

States, and Abyei.

This was in addition to a Cessation of Hostilities,

which proved a strong catalyst to the peace process

culminating in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in

Nairobi on 9 January.

A power and wealth-sharing government is to be formed

in August as part of the peace deal that also

prescribes a referendum after six years in the south,

to decide if it wants to join the north in a united

Sudan or become an independent entity.

While the end of the war in the south has brought

relief to a war-tired country, the implementation of

the power and wealth-sharing accord, in the face of

Sudan’s newfound oil wealth, is not going to be easy.

Also, peace in the south is only part of the story, because

another separatist war, which erupted in February 2003,

is still raging in the western region of Darfur, after

claiming 180,000 people and displacing two million others.

For the entire country to enjoy peace, and especially for

the peace process to endure in the south, all stakeholders

in the vast country – government, opposition, civil society,

including faith-based organisations, and the population at

large – must strive to end the battle over the three Rs – race,

religion and resources – fuelling Sudan’s conflicts.