FEATURE- Keeping the peace alive in Sudan

By Julie Flint, The BBC News

LONDON, Aug 11, 2005 — The first time I met Garang was in 1992 and he was not at all what I had expected.

I had been told he was aloof and did not take kindly to criticism but I found him to be warm, welcoming and surprisingly frank.

Under pretty harsh questioning about his human rights record, he admitted that the behaviour of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, which he led, left much to be desired.

|

|

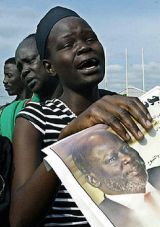

A Sudanese woman wails as the casket with the remains of John Garang is carried by a Sudanese Army detachment at the airport in Juba, southern Sudan for the burial. Garang died in a helicopter crash.(AFP) . |

We’ve lost our way,” he said. “Unless we change, we risk losing the trust of our people.”

Garang died before he could face a popular vote but I think it is fair to say that most southern Sudanese revered him for his unfaltering opposition to the central government – an Arab-dominated government – that shamefully neglects Sudan’s non-Arab peripheries.

But southerners deplored the factionalism that plagued the SPLA and the undisciplined behaviour of many of its soldiers.

And they made clear that the buck stopped with the SPLA’s leadership, commander-in-chief included.

Inter-tribal battles

The closest Garang ever came to a popular vote was during a grassroots peace movement initiated in 1999 to end years of factional fighting and inter-tribal battles – battles that took tens of thousands of lives in the south and often overshadowed the war with the government.

The people’s verdict on the SPLA was overwhelmingly negative.

“When we fought with your fathers, we never, never killed a child, a woman or an old person like me,” an elderly chief told young soldiers attending the first of the grassroots meetings in the little village of Wunlit.

“Where did you get this culture of killing from? You got it from the SPLA.”

In meeting after meeting, southerners shouted their opposition to the “PhDs”, as they called them, who led the two main rebel factions.

One was John Garang, a university graduate and member of the Dinka tribe, south Sudan’s largest tribe; the other was Riek Machar, a university graduate and member of the Nuer tribe, the second largest tribe.

The hero of Wunlit was Salva Kiir, the SPLA’s chief of staff and now Garang’s successor as first vice-president of Sudan.

He is the first southerner ever to hold such high office (apart, of course, from Garang himself) .

Had it not been for Salva Kiir – known simply as “Salva” in southern Sudan – there might never have been a Wunlit.

Peace covenant

In that case, Nuer and Dinka would not have signed a peace covenant and the tens of thousands of Nuer, who are soon to be driven from their homes on the east bank of the Nile by government attacks to control oil deposits there, would not have found safe refuge among the Dinka on the west bank.

|

|

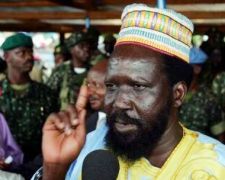

Salva Kiir, the new leader of SPLA/M, makes a point during a mourning for former rebel leader John Garang in Yei village in Southern Sudan August 5, 2005. (Reuters). |

Despite the opposition of many SPLA commanders to the “people to people” process, Salva committed himself from day one.

When a local commander threatened to stop the Wunlit conference by force, Salva warned him to back off.

“This is a trial of strength between us,” he said, “and I will win!”

He sent 250 of his own men to guarantee security.

He opened the conference, but then took a back seat. It was the first time that the SPLA had been a genuine “people’s” army – at the service of the people and unafraid of their criticism.

Garang’s death has caused concern for the future of the North-South agreement that was signed in Nairobi seven months ago.

It is true that Salva does not have Garang’s long political experience.

But he was the SPLA’s chief negotiator in the early stages of the peace talks and won respect there for his pragmatism and his willingness to compromise.

Greater democracy

Although few are saying it openly, the consensus among most Sudan-watchers, and many southerners too, is that a South Sudan government led by Salva will be more democratic, more conciliatory and more efficient than a government led by Garang.

Salva was one of Garang’s most vigorous critics, constantly demanding greater democracy and accountability within the SPLA.

He is not one of the “PhDs” whom southerners blame for their divisions: he is no fool but he never went to university.

He began fighting the government at the age of 19 and has been a soldier ever since.

The handover of power in South Sudan has been astonishingly smooth.

Salva was appointed Garang’s successor by unanimity within 24 hours of his death.

In a first gesture of reconciliation, he invited to Garang’s funeral the children of the founders of the SPLA – some of whom had been killed in fighting with Garang loyalists.

He has sidestepped questions about his disagreements with Garang most elegantly, saying: “Whether his style was good or not is no longer relevant.”

A soldier, then, but a soldier with skills far beyond soldiering.

So far, so good.