Sudanese refugees feel unwelcome in Cairo

By Daniel Williams

Feb 27, 2006 (CAIRO) — On a dirt lane in the poor Arba wa Nus neighborhood, Malles Tonga, a Sudanese refugee, spoke loudly about the brutality of Egyptian police and blamed President Hosni Mubarak for their behavior.

Suddenly, an Egyptian merchant emerged from a nearby dry-goods store, shouted an Egyptian slur for black Africans and yelled: “If you don’t like it here, go home!”

Suddenly, an Egyptian merchant emerged from a nearby dry-goods store, shouted an Egyptian slur for black Africans and yelled: “If you don’t like it here, go home!”

The use of the expletive exemplifies the plight of Sudanese who come to Egypt as refugees: They fear going home, but the welcome mat in Egypt, always thin of resources and tolerance, is almost threadbare.

The situation of Sudanese in Egypt brings to light the special difficulties refugees face when they flee a war-ravaged and impoverished land for another poor country. Egypt is in many ways an inhospitable place for its own citizens. In Arba wa Nus, Egyptians share with the Sudanese arrivals the neighborhood’s open sewers, dusty alleys, lack of plumbing and precarious chockablock housing.

But dark-skinned Sudanese Christians stand out among the Egyptians, typically lighter-skinned Muslim Arabs. Human rights workers say the Sudanese are subject to taunts, discrimination and violence.

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees has registered about 24,000 Sudanese refugees here, but independent observers estimate there are hundreds of thousands. Unlike in some other African countries, Sudanese in Egypt are not granted blanket U.N. refugee status, which would open the possibility of resettlement.

Under a bilateral arrangement, Egypt permits Sudanese to live and work in the country, but U.N. approval for asylum results only after a laborious interview process.

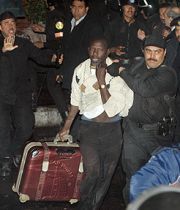

A breaking point for many Sudanese came on Dec. 30, when hundreds of riot police stomped through a makeshift camp in central Cairo to clear it of 2,500 refugees, trampling or beating to death 28 people, among them women and children, according to witnesses.

Few outside witnesses saw the melee, and accounts in this article were pieced together from Sudanese refugees. In late September, a few refugees had gathered at Mustafa Mahmoud park in Mohandessin, an upper-middle-class neighborhood, to demand full refugee status from UNHCR, with the possibility that they could be resettled somewhere in Europe, the United States or another wealthy country.

The refugees were worried that they would be forced to return to Sudan. Many had fled southern Sudan, the scene of a 21-year civil war that pitted black African separatists, most of them adherents of traditional beliefs or Christianity, against a Sudanese government run by Muslim, Arabic-speaking northerners who had tried to impose Islamic law on the country. A peace agreement was signed in January 2005, but the refugees reject the notion that repatriation to Sudan is either safe or viable. Roads are still mined, villages are bare and violence flares on occasion. A separate civil war rages in the Darfur region of western Sudan.

The number of refugees involved in the protest grew, unusual given Egypt’s ban on any gathering of more than five people. The demonstrators set up plastic tents and formed their own security contingent.

Riot police began to gather on the night of Dec. 29. Big blue troop trucks surrounded the square and officers aimed water hoses at the demonstrators. After midnight, with the desert cold gripping the city, water was poured on the camp. Some of the police yelled, “Give it to them. They need a shower,” witnesses said.

Before dawn, the police marched into the camp wielding sticks and truncheons. Some refugees pulled poles from the tents to fight back, witnesses said. Some of the children were huddled under the collapsed tarps, Tonga recalled. “The police just marched in and stepped on everything and everyone,” he said.

Tonga said he was hit on the back of the head and knocked unconscious. He awoke in one of several military camps outside Cairo where 1,000 detained refugees were bused.

Earlier this month, the last 156 of about 2,000 migrants arrested during the December violence were released from jail. “The Egyptian authorities have set free all the Sudanese who were transported to the detention centers after putting an end to their strike,” a Foreign Ministry official said. They were illegal immigrants, the official told reporters in Cairo, but would not be deported “for the sake of not scattering the Sudanese families who live in Egypt.”

The refugees think they lost. Amer Gaber, who belongs to a group called Sudanese Refugee Voice and helped organize the protest, said, “We got some attention, but internationally, there was not much reaction.”

U.N. refugee officials, whose office is a half-block from the scene of the violence, are fighting accusations that, by urging the police in, they were responsible for the massacre.

Astrid van Genderen Stort, the UNHCR spokeswoman in Cairo, said demands for resettlement are unrealistic; countries, not the United Nations, make the decision to admit individuals. “It is not a gift that we can pull out of our pocket,” she said. Repatriation to Sudan is voluntary, van Genderen Stort said. She noted that UNHCR resettled 3,700 Sudanese out of Egypt last year.

UNHCR and refugee leaders had reached an agreement on Dec. 17 to review asylum requests and provide new aid, but some demonstrators refused, the agreement fell apart and the protest continued, van Genderen Stort said. “People began to think that the longer they were on the square, the more likely they could get out of Egypt,” she said. “They became like children who thought they could get something just because they wanted it.”

Barbara Harrell-Bond, a visiting professor of refugee studies at the American University of Cairo, criticized UNHCR for failing to grant Sudanese blanket refugee status in Egypt and for suggesting that they could voluntarily return to Sudan. “Return to what?” she said. “There are internally displaced people in Sudan as it is. Sudan is not stable. The fact that refugees don’t go back indicates they can’t go back.”

The Egyptian government maintained that it did the right thing by clearing the square.

Foreign Minister Ahmed Aboul Gheit said Egypt “dealt with the sit-in with wisdom and patience.” Egypt’s Interior Ministry said police were protecting UNHCR, which it said received threats of attack on commission offices and staff.

In Tonga’s mind, such statements demonstrate the weight of discrimination and intolerance. “We need to be settled somewhere else,” he said.

As a metalworker, Tonga said, he earned the equivalent of $2 a day, about half of what an Egyptian would be paid, but he left his job because he was afraid. “The Egyptians hate me because I worked for less than them,” he said. “God, how I wish I could get paid what they do. But we are discriminated against.”

Tonga fled Juba in southern Sudan in 1992 for Khartoum, the capital, after his brother was killed in the war. In 1999, he was arrested and accused of secretly working for southern rebels. He was jailed, caned, kept on low rations for a week, then released, he said.

Using fake documents, he fled to Cairo, where he won asylum status from UNHCR. But Tonga said he wanted to be resettled in the West. “I felt that Egypt was no good for us before the killings,” he said.

Returning to Sudan is not an option, he said. “Who will protect me when I am there? I was tortured once and that was enough,” he said.

Tonga lives with seven men in a room built into a ground-floor recess of a tenement in Arba wa Nus. Their toilet is a walled-up hole in the ground. Water drips from a pipe connected to another house; Tonga bathes by bending down and sticking his head under the faucet.

He spends his days in the dirt alleys of Arba wa Nus huddled in conversation with other refugees or seeking handouts from churches. Goats roam the neighborhood. Egyptian carpenters and stonecutters labor outside workshops.

On a recent morning, Tonga shared tea with a compatriot, Yusef Teet, who fled fighting in Sudan in 2001. As the two men drank, a group of Egyptian boys strolled by, laughed and murmured, “Donkey, donkey.”

Teet shines shoes for a living, bringing in the equivalent of 30 cents on a prosperous workday. Most people in Arba wa Nus wear rubber sandals, not shoes.

In Sudan, Teet had wanted to be a physician, but completed only one year of high school. In a corner of his room rests a single book in English on anatomy. “I have ambitions!” he exclaimed.

He shares a room with two other Sudanese. They sleep cheek by jowl on thin cotton mats. Teet dreams of going to Libya, where he might be able to catch a boat to Italy. “But the smugglers want $1,000,” he said, “and you can die in Libya and no one will know about it.”

When police raided the protest encampment, Teet was captured and bused out of Cairo to a military camp. He said they took his sandals, so when they dropped him off back in town, he had to walk barefoot to Arba wa Nus, several miles away.

“They call us beasts and black dogs here. Maybe I will go back to Sudan,” he said, adding that after the recent violence, “it is better maybe to die there than live with these miserable people.”

(The washington Post)