Sudan’s Garang left a legacy of what-Ifs

July 16, 2006 (JUBA) — His memorial appears untouched since the funeral a year ago. Temporary aluminum roofing covers baskets of dusty plastic flowers. Tattered flags and fading tinsel hang limply from metal beams.

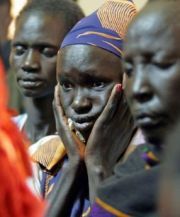

Yet each day, visitors stream by to pay their respects to Sudanese rebel leader John Garang, who led a 21-year civil war against the government before signing a landmark peace deal, only to die six months later in a helicopter crash.

Yet each day, visitors stream by to pay their respects to Sudanese rebel leader John Garang, who led a 21-year civil war against the government before signing a landmark peace deal, only to die six months later in a helicopter crash.

Around Juba, the dilapidated capital of southern Sudan, many can’t help but wonder what might have been.

Would Garang have secured a stronger role for his fellow southerners in the new coalition government led by his onetime archenemy, Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmed Bashir? Would Garang have made good on his pledge to resolve the standoff in the western region of Darfur, which has worsened since his death? Would he have pushed for faster development in the long-neglected south?

“If Garang were still around, life would be different,” said Samuel Gouorid, 41, leaning over his stand of eggplant and limes in Juba’s central market.

It’s a common refrain these days in Juba. For decades, people here blamed Khartoum for their plight, accusing the northern government of abandoning the south, first in retaliation for the civil war and, later, to more easily seize control of its oil resources.

But a year after a new southern government won autonomy for the region, little has changed, residents say.

The city still lacks widespread electricity and running water and has only two paved roads. Land mines from years of battle remain buried around the capital’s outskirts. Housing and land prices are skyrocketing because of the influx of government and aid workers. Tented campsites charge $150 a night.

Some, however, see modest improvement. Repairs to the highway linking Juba to the border with Uganda have yielded daily shipments of fresh cabbage, pineapple and bananas. Prices for a large sack of corn have plummeted from $35 a year ago to $6 today thanks to increased supply.

Furniture salesman Garang Abany, 36, said that he recently sold three $7,000 bedroom sets, newly imported from Dubai. Such luxury sales had been unheard of.

But progress remains uneven. At the shabby two-story statehouse for the region, government workers use Windows XP and high-speed Internet, but toilets still don’t work and there are holes in the walls.

“If Garang came back and saw what was happening,” said Venansio Tombe Muludiang, deputy vice chancellor at Juba University, “he would go back to his grave.”

Leaders charged with filling Garang’s shoes said such impatience was not surprising. Rebecca Garang, the rebel leader’s widow, who heads the Ministry of Roads and Transport in the southern government, said a $777-million construction and refurbishment project for Juba only recently received the go-ahead. It’s taken a year to put rules and financial guidelines in place for selecting and paying contractors, she said.

Decades of underdevelopment by the Islamist government in Khartoum contributed to delays, making construction expensive and time-consuming. Supplies are not available locally, so it costs $48 to transport a $6 bag of cement to Juba, said Gary McGurk, assistant country director for CARE International, an aid group working to open an office in Juba.

Rebecca Garang emphasized that her husband realized that improvements would take time. She said he would be thrilled to see that the peace deal he negotiated and the political movement he founded were still in place.

“He knew implementation of peace would not be easy,” said Garang, a former rebel commander. “He knew there would be ups and downs. But he would be happy to see that we are continuing with the struggle. Things are going slowly, but in the right direction. We are doing exactly what he would have done.”

In January 2005, John Garang and Bashir signed a U.S.-brokered peace deal that ended Africa’s longest-running civil war, which pitted Christian and animist rebels in the south against the Muslim Arab-dominated government in Khartoum. The conflict killed an estimated 2 million people, most of whom died of disease and hunger, and displaced 4 million.

A year ago, Garang made a much-heralded return to the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, to take his role as vice president in the new coalition government. Millions greeted his return, fueling speculation that Garang could pose a serious threat to Bashir in free elections by uniting opposition groups in the south, west and east.

Less than a month after he took office, Garang’s helicopter crashed in bad weather July 30. Official investigations blame pilot error, but many of Garang’s supporters suspect foul play.

Garang’s successor, Salva Kiir, has won mixed reviews. The military leader, who was Garang’s No. 2 and occasional rival in the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, lacks the charisma of his predecessor but has managed to keep the southern government united.

“We’re working as a collective leadership now, with one spokesman: Salva Kiir,” said Riek Machar, another Garang deputy, now serving as vice president of the south.

Comparisons with Garang are inevitable but unfair, Machar said, because Garang never had the chance to demonstrate his governing abilities. “We have nothing to compare against,” Machar said. “Garang didn’t survive that long of a time in Khartoum. Only two weeks. You can’t really say that one is better than the other.”

Kiir, who serves as vice president of the national government and president of the south, has taken a more conciliatory approach than many believe Garang would have. After taking charge, Kiir reached out to rival southern militias and incorporated them into the southern government, something Garang appeared unable or unwilling to do.

Kiir’s compromises with Khartoum have been less popular. After Garang’s death, Bashir’s National Congress Party insisted on retaining control of the coveted Oil Ministry, which was expected to go to the SPLM.

Most of Sudan’s oil reserves are in the south, but southerners only recently received their first installment of oil profit – about $800 million – under a 50-50 sharing provision in the peace deal. Kiir and others complain that they have been unable to review production and financial figures to confirm they are receiving their fair share.

Other government ministries were stripped of key powers before being handed over to the SPLM, officials said, pointing out that control of the airports was removed from the Transportation Ministry.

In recent weeks, Kiir has been intensifying the rhetoric against Khartoum. He said key elements of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement remained unresolved, including control of the key oil city of Abyei, final demarcation of the north-south border and distribution of oil profit.

“Unless we make progress on these matters, I cannot see how the rest of the CPA can survive,” Kiir said recently.

Other southern Cabinet members were more blunt.

“They are not dealing in good faith,” said Samson Kwaje, information minister for the south. “They are buying time and hoping to sabotage it later.”

In a sign of the growing tension in the coalition government, Kiir publicly broke with Bashir recently over the president’s opposition to deployment of United Nations troops in Darfur. SPLM leaders have also expressed skepticism over a peace deal reached in Darfur, saying it has only served to divide rebels in the west.

But Kiir must be careful to assert the SPLM’s position without cracking the fragile coalition government, his supporters say. Under the terms of the peace deal, the two sides agreed to work together until 2011, when southerners will get the chance to vote on secession.

“We’re locked into this relationship,” Machar said. “We’re trying to give it chance.”

(Los Angeles Times)