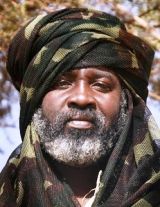

Profile: SLA rebel commander relays Darfur tribes’ woes

March 15, 2007 (AMARAI) — Jar al-Naby was once a high school biology teacher, but Darfur’s turmoil turned his life upside down. Two of his children and his brother are now dead, and he is a rebel commander.

“It didn’t always used to be this way,” the 43-year-old al-Naby said, stroking his graying beard. “But life had simply become impossible,” he said, referring to discrimination by the Arab-led Sudanese government that ethnic Africans say triggered their rebellion in Darfur in 2003.

Since then, the conflict has killed more than 200,000 people and driven more than 2.5 million from their homes. The government is accused of trying to rein in the rebels by unleashing the janjaweed, Arab tribal militias blamed for widespread atrocities against ethnic African civilians.

Al-Naby and his fighters, a tiny part of the Sudan Liberation Army – the largest rebel group – operate in a desert region about 30 miles north of Kutum, the North Darfur town al-Naby once called home. It is now held by government troops.

Several top commanders in Darfur’s rebellion were senior officials in the Sudanese government, but broke with it to launch the insurrection. Many midlevel commanders, like al-Naby, were once teachers, some of the few educated people in the impoverished region.

The SLA, like all rebel groups in Darfur, is highly decentralized with hundreds of midlevel commanders each living in part of the vast region and commanding a few hundred men in most cases. At a recent secret conference, the factions sought greater unity, but so far it is unclear if those efforts have succeeded.

Overall, the Sudanese Liberation Army is thought to have several thousand fighters, and it is difficult to gauge their success. The government claims to have cornered them in one part of Darfur, but an Associated Press reporter who traveled through northern Darfur recently saw rebels operating across the region and little evidence of government forces.

The rebels seek to pressure the government to agree to a deal that will include more services for the people, the disarming of the janjaweed and compensation for refugees.

Al-Naby, who says he now commands a few hundred men, had hoped for a future elsewhere. After obtaining a biology degree in Libya, he wanted to study in Europe or North America.

“But there were already so many problems with the Arabs in Darfur that my family asked me to come home,” he said. So he took a job as a biology professor in a North Darfur high school in the mid-1990s.

He said that when the rebels began fighting the government in 2003, he was not part of it. But because he belongs to the Zaghawa tribe that spearheaded the rebellion, he was repeatedly arrested.

“The last time I was released, it was only because they needed teachers to correct the biology exams in Khartoum,” he said, chuckling.

A few months later, the janjaweed raided Kutum. Al-Naby said he survived by fleeing across rooftops, then joined a camp of rebels. He had never used a gun before, he said, but learned to fight Sudanese troops and the janjaweed.

“We spent two days fighting in these rocks,” he said, pointing to large granite boulders on the barren plain, where he said he and 17 other rebels battled government forces.

Since then, this area has been relatively peaceful. Al-Naby said he brought his wife and children to the safety of a traditional Zaghawa mud hut compound here because they were in danger in Kutum.

That meant giving up modern comforts like electricity, running water and access to medical care. Two of his five children have since died of illness.

Al-Naby’s two remaining daughters now go to school under false names in a distant Darfur town, and he hasn’t seen them for nearly a year. Soon his 5-year-old son, Hamoudi, also will leave to go to school.

“The children will all go together,” he said, pointing to several nephews and nieces he adopted after his only brother, rebel commander Hassan Bijo, was killed in combat last December.

The SLA has been plagued by infighting, which al-Naby blames on the poor education of most leaders.

“How can you be expected to organize a unified movement or negotiate a peace treaty with the United Nations when you’ve spent most of your life attending camels?” he asked.

In 2004, commander Minni Minawi took control of a branch of the SLA, splitting the group into factions. Minawi signed a peace deal with Khartoum in May 2005, and became part of the government.

But the vast majority of rebel commanders, including al-Naby, rejected the deal. They say they need stronger guarantees that the government will disarm the janjaweed and compensate victims.

In a notebook, al-Naby meticulously records what he hears about attacks on refugee camps or government air raids.

“We were already neglected before,” he said. “But now the conflict is bringing us even more backward.”

(AP)