Evicted From Camp, Sudan Refugees Suffer in Limbo

By MARC LACEY, The New York Times.

EL FASHER, Sudan, Aug. 2 — Aid workers call them ”Kofi Annan’s group.”

When Mr. Annan, the United Nations secretary general, pulled up at the dismal Meshtel refugee camp during a visit to Darfur on the afternoon of July 1, to his surprise every last person was gone. ”Where are the people?” he was heard to ask.

A month later, he and other dignitaries have come and gone, but some 1,500 people from Meshtel remain in limbo. They were sent to another camp, Abushouk, but have not been completely welcomed and live a few degrees of destitution below the rest of the 50,000 displaced people there.

The new residents have yet to be formally registered, despite a month of waiting. That means they have not been entitled to plastic sheeting, free blankets or food rations from aid agencies, no matter what tragedies they may have endured.

Among the others in Abushouk, these down-and-out people are referred to with the same Arabic word given to used clothes. The nickname, Abu Janguer, comes from their hovels, many of which feature garments as roofs.

”We feel awful when they call us that,” said Sara Abubakar Musa, 24, who was displaced by armed militias from her village several hours north of El Fasher. ”How can they give us such a name?”

Ms. Musa was among those whom Mr. Annan never got to meet. On the eve of his visit, she recalled, government trucks showed up at Meshtel, a camp generally more squalid and unsightly. She said people had been ordered to grab their possessions and go — not home, but to Abushouk, on the outskirts of town, ensuring that Mr. Annan would not see their severe hardship.

Such forced relocations have occurred here and in other parts of Darfur, Sudan’s troubled western region, where more than a million people have been driven from their homes. As recently as this week, government officials were offering cash, food and other incentives to lure people living in resettlement camps back to their villages. Then there are those like Ms. Musa who are simply made to move.

The aid workers condemn the government practice of trying to lure the displaced people back to their villages, but it is the residents themselves who typically speak out the loudest. Most say they will not go home until they are assured that Darfur is safe.

By nearly all accounts, a month after the high-profile visits from Mr. Annan and Secretary of State Colin L. Powell, it is not. This is so despite increasing pressure — including a United Nations Security Council resolution implying sanctions — on Sudan’s government to rein in marauding militias, known as the Janjaweed. The United States Congress and others have called the killings in Darfur genocide.

This vast region of scrub and sand is still marked by tension, insecurity and lawlessness, driven either by run-of-the-mill bandits or the Janjaweed militias, which the government has armed and backed in its conflict with two rebel groups.

The rebels have fought since early 2003 for more resources for the black African majority in Darfur, which they say has been neglected by a government in Khartoum dominated by Arabs.

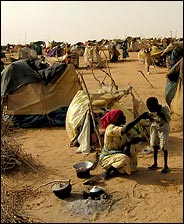

Camps like Abushouk are where the thousands caught in the middle of the conflict find refuge in neat rows of huts, each covered with plastic sheeting to keep out the rains.

Mr. Powell came to Abushouk in late June and suggested afterward that he knew that conditions elsewhere in Darfur were much worse, despite the government’s best efforts to hide the worst of camps, like Meshtel. There are two health clinics in Abushouk, and evenly spaced latrines. So organized is this camp that road signs have been stuck in the sand.

But Abushouk has a bad neighborhood too. That is where Ms. Musa and the others transferred from Meshtel continue to live in squalor compared with their compatriots in other parts of the camp. Old clothes hung on wooden poles are all that protect them from the elements. They relieve themselves in the sand.

Many here lived with relatives in El Fasher after being forced out of their villages by armed militias. But when they saw other displaced people receiving benefits, they began camping out at Meshtel. Their approach failed, and they were moved once again.

The other day, several hundred of those moved from the Meshtel camp looked on as aid workers gave out rations to other residents of Abushouk. When people from Meshtel would step forward, without the required registration card, the authorities would push them back. The giveaway finished, and the only people left, unfed, were those from Meshtel.

Help may be on the way. The International Committee of the Red Cross, which coordinates aid in the camp, says it intends to begin providing assistance to the people from Meshtel soon.

”These people were brought in all of a sudden, with no organization,” said Jean-Francois Sonnay, head of the Red Cross office in El Fasher. ”We hope to start distributing to them in the next few days.”

And officials at the World Food Program said the people from Meshtel will soon be added to its ration list. But the people themselves have heard nothing, which is by design. Aid workers fear that if word gets out, residents of the nearby town will flock to Abushouk.

Until the aid does arrive, the outcasts whom Mr. Annan almost met are confused by the treatment they are receiving.

”We don’t know why we don’t get the same as everyone else,” said Ms. Musa, whose two children are recovering from malaria. ”No one wants to register us. It’s not fair. Everybody is suffering, but we’re suffering even more.”