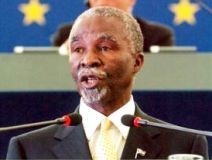

South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki carves role as point man for peace in Africa

By TERRY LEONARD, Associated Press Writer

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa, Nov 22, 2004 (AP) — On a continent dominated by despots and beset by war, South African President Thabo Mbeki has emerged as the man increasingly called upon to stop the bloodletting.

While he has had only limited success so far, Mbeki remains the leader both the West and Africa turn to for help in brokering solutions to some the most intractable conflicts on the continent.

While he has had only limited success so far, Mbeki remains the leader both the West and Africa turn to for help in brokering solutions to some the most intractable conflicts on the continent.

Partly it is because of South Africa’s dominant economic role in the continent’s affairs, but it is also because Mbeki cultivated close contacts across Africa as a former exile in the struggle against apartheid.

Through South Africa’s efforts to bring peace to Sudan, Congo, Ivory Coast and Burundi, an Mbeki doctrine has emerged — one that favors dialogue, compromise and a sensitive ear to the concerns of all parties.

“It is this notion that conflicts in Africa are best resolved by inclusive political settlements,” said Steven Friedman, a senior research fellow at South Africa’s Center for Policy Studies.

Mbeki always looks for a starting point, a tiny acre of common ground. Friedman said he rarely takes sides and doesn’t see good guys and bad guys. Instead, he struggles to get both sides to settle for only part of what they want in the interest of peace.

Powersharing, transitional governments and reconciliation are always part of Mbeki initiatives. It is a formula the South African leaders believes ended apartheid and avoided bloodshed in South Africa.

Now, it is the model he pushes for the rest of the continent.

So in Burundi, Mbeki encourages Hutus and Tutsis to form a temporary government of national unity as they work toward elections. In Ivory Coast, he wants both sides to commit to previous cease-fire agreements as a building block for peace.

At the core of the Mbeki doctrine is the belief he shares with U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan that without peace, Africa cannot develop.

“Getting Africa’s political house in order is part of the doctrine,” said Richard Cornwell, a senior researcher at South Africa’s Institute for Security Studies.

In Burundi, South Africa claims to have brokered a general agreement on a power-sharing formula to end fighting between Hutus and Tutsis. But the major Tutsi party has rejected the agreement over concerns about who will represent them in any new government.

South Africa helped guide Congo and the five other countries involved in its civil war to a peace agreement in July 2003. The agreement creates a transitional government and sets elections for next year. However, Mbeki has had to intercede to keep rebels in the transitional government, which remains fragile.

Mbeki’s efforts at “quiet diplomacy” in Zimbabwe have shown little or no progress to date at getting the Southern African nation to restore the rule of law and end violence and intimidation against the political opposition.

Mbeki is the staunchest advocate of African Renaissance, a movement of social and economic recovery he believes is sweeping the continent. He is one of the authors of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development, a program for economic revival and good governance adopted as the African Union’s economic and political blueprint.

He also has said repeatedly that South Africa’s future and its own economic development is linked to whatever happens in Africa as a whole.

Mbeki’s strategy for peace both in Africa and elsewhere relies heavily on multilateral institutions such as the United Nations and the African Union.

As the first chairman of the African Union, Mbeki led the body to successful interventions in Congo and Burundi. He works through the African Union to try to ease the crisis in the Darfur region of Sudan. He was the man the AU picked to deal with renewed fighting in Ivory Coast.

Through his commitment to the AU, Mbeki has sent peacekeepers to Congo and Burundi and observers to Darfur.

Besides Ivory Coast, Burundi, Congo and Sudan, Mbeki has worked to resolve conflicts between Ethiopia and Eritrea and internal conflicts in Angola, Madagascar and the Comoros.

“He is a very cerebral man with a tremendous mastery of details,” said Cornwell.

At home, Mbeki is usually hailed as a point man for peace in Africa. The one glaring exception is Zimbabwe: Mbeki’s “quiet diplomacy” is as “silent diplomacy” by critics.

Many believe that crisis is too close to home. Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe may be seen as a tyrant now, but he was a hero of the Zimbabwean liberation struggle. He was also a friend and benefactor of South Africa’s anti-apartheid campaign.

South African regional power stems largely from economic leadership — it is by far the most prosperous country on an impoverished continent.

It leads in industrial output and mineral production and generates more than half of the continent’s electricity. Its gross domestic product is four times greater than that of its southern African neighbors and accounts for 25 percent of the continent’s total.

“He would not play as big a role if he was the president of Botswana,” said Friedman.