War-scarred south Sudan faces even bigger challenge winning the peace

KHARTOUM, Dec 31 (AFP) — Even before rebels took to the bush in 1983, southern Sudan was one of the least developed regions in Africa. Now, after more than 20 years of war, vast swathes are virtually devoid of people.

A landmark peace deal initialled Thursday gives the rebels a 50 percent share of Sudan’s oil revenues to set up an autonomous administration — or around 1.5 billion dollars a year on present earnings.

A landmark peace deal initialled Thursday gives the rebels a 50 percent share of Sudan’s oil revenues to set up an autonomous administration — or around 1.5 billion dollars a year on present earnings.

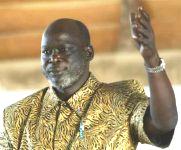

But rebel leader John Garang makes no secret of the herculean challenge his administration faces in winning the peace.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that three and a half million out of southern Sudan’s 10 million people have been displaced by the war, 500,000 of them beyond Sudan’s borders.

Of those, 223,000 have found refuge in Uganda, 88,000 in Ethiopia, 69,000 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and 60,000 in Kenya.

The UNHCR has said it hopes to assist 150,000 refugees and 80,000 internally displaced to return to their homes in the first 18 months of peace.

In June, the agency’s assistant high commissioner, Kamel Morjane, appealed for 90 million dollars from UN member states to fund a two-year repatriation programme.

But just getting the refugees home poses enormous difficulties.

In an area bigger than France and Italy combined, southern Sudan has hardly any paved roads, and most of the dirt tracks that do exist are heavily mined.

In September, South African sappers began work demining hundreds of kilometres (miles) of piste road from the Kenyan border to the rebel-held town of Rumbek.

The town is capital of El-Buheyrat (Lakes) state and is seen as a likely seat for the new regional government even though much of it is currently in ruins as a result of countless bombing raids.

“We are literally starting from scratch,” Garang told AFP in an interview in the town earlier this year.

“Our priority begins with infrastructures, because really if things cannot move, the economy cannot function.

“We haven’t had tarmac roads since creation. We have to open a waterway for navigation of the Nile so that we link with the north, and we must rehabilitate the only railway line we have.”

The war also took a heavy toll on education in the south, where a mere 1,000 people out of 10 million are estimated to hold a university degree, creating a dearth of trained professionals.

In the vast tent cities that sprang up to accommodate the displaced, schooling was not the most pressing priority.

Those inhabitants not dependent on aid handouts largely live by subsistence cattle-herding.

Power supplies and telephone links are largely non-existent, while only the handful of garrison towns which remained under government control throughout the war escaped the devastation of shelling and air raids.

The Khartoum government hopes to boost its oil output to 500,000 barrels per day next year from 350,000 currently, raising the prospect of increased revenues for the regional government which is to administer the south up to a referendum on independence in six years’ time.

And ambitiously the rebels have already set up an embryonic central bank in Rumbek — the Commercial Bank of the Nile.

But Garang makes no secret of the challenges ahead. “We’re going to have to fight,” he told AFP. “But this time without weapons.”