Guns stop ‘crying’ in southern Sudan

By Emily Wax, The Washington Post

RUMBEK, Sudan, Jan 23, 2005 — Southern Sudanese women wearing skirts made from plastic bags sang victory songs as they waited for their leader’s plane to touch the tarmac.

|

|

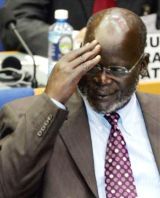

John Garang, Chairman of the SPLM/A . |

Scouts in khaki outfits shooed goats off the runway. And barefoot children climbed onto a rusted-out plane, clasped hands and chanted: “Our guns are crying no longer. We are at peace.”

After 21 years of fighting between the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army and the Islamic government, John Garang, the rebel leader, returned Saturday to the group’s headquarters in Rumbek, 560 miles south of the capital, Khartoum, after signing a peace deal two weeks ago in neighboring Kenya.

“It feels great after a peace agreement — honorable and dignified,” said Garang, whose once wild beard was now trimmed. “You can see the people are very happy.”

The accord between the government and the rebels based in the mostly animist and Christian south ends a war that left 2 million people dead, primarily from famine and disease, and 4 million homeless.

The agreement gives the south religious autonomy and a share of the country’s oil riches. After a six-year interim period of self-rule, residents of the south will vote in a referendum on whether to remain part of Sudan or secede. The agreement also calls for Garang to become Sudan’s first vice president, and his swearing in as part of an attempt to unify the government is expected within months.

But the deal, signed Jan. 9, does not cover an unrelated conflict festering in Sudan’s western region of Darfur, where tens of thousands have died and nearly 2 million people have been driven from their farms and into crowded camps.

“We will work for peace for Darfur,” Garang said later at a rally. “We cannot have peace in one part of the country and war in another.”

Analysts said Garang, who has been accused by the government of backing rebels in Darfur, could play an important role in bringing peace to that region.

After the rally, a visiting U.N. envoy, Jan Pronk, said he hoped Garang would use his influence to bring peace to Darfur.

“Let’s just hope they come to peace in a shorter period,” Pronk said.

At a news conference Sunday, Garang said his movement, known as the SPLA, could help solve the Darfur crisis. “We know the Khartoum government, and we know the rebel parties,” he said. “There needs to be a fair and just settlement in Darfur. The SPLA will be helpful on all sides to do what it can do.”

Fighting in Darfur started in February 2003 when African rebel groups took up arms against the government, demanding greater representation and economic development. The government has accused the rebels of using civilians as human shields and responded by bombing villages and arming an Arab militia known as the Janjaweed.

The Darfur conflict has made many countries uneasy about investing in the south, which was expecting to bring in revenue from its oil resources.

On Friday, the Dutch minister for development cooperation, Agnes van Ardenne, visited Rumbek, one of the first foreign officials to visit the region since the peace accord was signed. Van Ardenne promised more than $150 million for development in the south but said the money would be withheld until the conflict in Darfur was resolved.

Southern Sudan suffered severely during the two decades of warfare. Life expectancy in the region is one of the lowest in the world, at 42 years. Most people live without running water and electricity. Jobs are scarce. Rickety bicycles are the main form of transportation.

In Rumbek, a dusty town without roads, high expectations are a part of every conversation. During Garang’s speech, one soldier broke into spontaneous song, singing: “For the last 20 years we starved. Now people who have gone to hide are back and looking for jobs.”

At the airport Saturday, Yusuf Makuac, 18, was one of hundreds in a crowd watching as Garang stepped over a slaughtered longhorn, a traditional peace offering in his Dinka tribe. Makuac, who said his father was killed in 2000 while fighting for the SPLA, said the rebels were “very happy, but we have a few requests.”

“We would like to ask for schooling. . . . We could even use a hospital and some training centers for skills. Maybe we could be like America one day,” he said.

Later, at the rally in Freedom Square, Gabriel Makur, 22, sat under a tree and watched the festivities somberly. He held a small, handwritten cardboard sign that read, “Peace for the South. Peace for Darfur.”

Twenty years ago, some of his Dinka relatives fled the violence in southern Sudan and relocated to camps in Darfur. Now they are stuck in Darfur’s war, prevented by the instability from returning to their homes.

“We keep praying,” Makur said, perspiring in the thick heat. “I don’t want my relatives to be forgotten. We are Darfur, and Darfur is us.”