Black Churches and Darfur Activism

By Religion & ethics newsweekly

Aug 19, 2005 — LUCKY SEVERSON, guest anchor: In Sudan, tensions remain high after the death of that country’s first Christian vice-president, John Garang, who was killed in a helicopter crash three weeks ago. Local religious leaders have been appealing for calm so that the fragile peace agreement in southern Sudan will hold. They’ve also urged that peace talks move forward in the troubled Darfur province.

Here in the U.S., a diverse coalition of Christians, Jews, and Muslims has been mobilizing on Sudan. Many African Americans were slow to join that coalition, but as Kim Lawton reports, black churches are now providing a new grassroots momentum for the cause.

Here in the U.S., a diverse coalition of Christians, Jews, and Muslims has been mobilizing on Sudan. Many African Americans were slow to join that coalition, but as Kim Lawton reports, black churches are now providing a new grassroots momentum for the cause.

KIM LAWTON: Sunday morning worship at St. Sabina Catholic Church in Chicago. There’s the usual emphasis on sin and salvation, but these days you’re also likely to hear about Sudan.

UNIDENTIFIED PRIEST: Come on, let’s do a dance for victory in the Sudan.

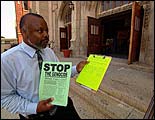

LAWTON: The predominantly African-American congregation has made Sudan — and especially the western region of Darfur — a major priority. And church members are focusing their considerable energies to end the crisis there. They’ve launched a new petition drive, calling on President Bush to take “strong and decisive action” to stop the violence and genocide.

The drive comes on the heels of a successful campaign to ban Illinois from investing state money in companies doing business in Sudan. The bill was introduced by St. Sabina member and State Senator Jacqueline Collins. In June, with strong lobbying from churches, Illinois became the first state to pass such legislation.

JACQUELINE COLLINS (Illinois State Senator): If we call ourselves “church,” we have to reclaim what our mission is in society as church. I think we are just living out the gospel.

LAWTON: The efforts are part of a national interfaith coalition raising awareness about Sudan. The coalition is religiously diverse and has been active for several years. Initially, African-American leaders were slow to join in. But now, black churches are increasingly moving to the forefront of grassroots activism on Sudan.

Reverend SEAN MCMILLAN (Pastor, Shekinah Chapel): What we’ve been able to do is to mobilize our numbers and to say that we’re willing, so to speak, to lay our bodies on the line, because there are certain things which all of our faiths, all of our deep religious understandings compel us to do.

LAWTON: The United Nations has called Sudan the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. An estimated two million people were killed during 20 years of civil war between the Arab Muslim north and the predominantly Christian and animist south. Famine, rape, abduction, and slavery all became weapons of the war. Nearly a decade ago, American evangelicals made Sudan a centerpiece in their growing campaign against religious persecution.

Dr. ALLEN HERTZKE (Professor, University of Oklahoma and Author, FREEING GOD’S CHILDREN): While it was a high priority among conservative evangelicals, it originally was just not on the radar screen of many black leaders.

LAWTON: University of Oklahoma professor Allen Hertzke has written a book about faith-based advocacy for human rights.

Dr. HERTZKE: The black churches were drawn into the struggle eventually — primarily because of the concern about slavery and the awareness that Africans were being abducted into slavery, thousands of them, by this regime in Khartoum.

JOE MADISON (Radio Talk-Show Host, DEMOCRACY NOW) (On Air): Madison with you here, it’s 28 after the hour on “The Power.”

LAWTON: National radio talk-show host Joe Madison played an important role enlisting black support. He says he got involved because he initially couldn’t believe the allegations of slavery. In April 2001, he and civil rights leader Reverend Walter Fauntroy traveled to southern Sudan.

Mr. MADISON: I literally broke down in tears in the middle of this barren area, under a mahogany tree. As an African American, seeing these Africans in this condition, [there] was just no way I was going to allow this to happen and not use whatever resources I had to change it.

LAWTON: Madison and Fauntroy returned and began high-profile advocacy, including getting arrested in front of the Sudanese embassy. They combined efforts with conservatives and urged their extensive contacts in the civil rights community to do so as well.

Mr. MADISON: Something that Reverend Fauntroy kept talking about was, “There’s a moral center here, Joe. We’ve got to find that moral center and work at it.” I just didn’t realize how difficult it was to find it, but we did.

(On Air During Radio Show): This is not a time, reverends and ministers and deacons, to be silent. This is a time to speak out.

LAWTON: Madison says there were several reasons for the initial black reluctance to get involved.

Mr. MADISON: Time after time, minister after minister would tell me, “I didn’t know.” That was number one. Number two, there was a disconnect between evangelical, conservative, Republican-oriented ministries and, in essence, the black church.

LAWTON: Some leaders felt it was more important to focus on the many challenges facing the black community in the U.S. In addition, says Chicago Lutheran pastor Sean McMillan, many African Americans have complex feelings about Africa.

Rev. MCMILLAN: We know that we are rooted in Africa, but our sensibilities, our cultural and moral sensibilities, tend not to drive us to appeal for their liberation the same way that we have been driven to appeal for our own.

DEMONSTRATORS (Shouting): Slavery plus genocide equals Sudan.

LAWTON: But the issue gained momentum in the black community. Many African-American politicians, civil rights leaders, and actors, including Danny Glover, have made Sudan a priority issue. They’ve launched a national divestment campaign similar to those against South Africa during the apartheid era.

In the last two years, as southern Sudan moved closer to peace, attention shifted to the western Darfur region, where conflict continues. Government-supported militias are accused of waging a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the local Muslim tribal population. The U.S. Congress has proclaimed the situation genocide.

Dr. HERTZKE: The grassroots energy on Darfur is now coming more from the black churches in many respects than from the white evangelical churches, which were so heavily invested in southern Sudan that they haven’t, in some cases, shifted course.

LAWTON: Evangelicals are involved in the Darfur issue, but Hertzke says some of their energies have been siphoned off to other issues, such as gay marriage and judicial nominees.

Dr. HERTZKE: The diversion of evangelical energies to other issues has in fact opened the way for the black churches to fill that void in grassroots momentum.

LAWTON: Social justice organizer Romal Tune says the Darfur activism is in the tradition of the civil rights movement.

Reverend ROMAL TUNE (Social Justice Organizer): It was based on the power of the communities — people who were tired of a given condition and wanted to bring about change. And if we cast a vision of a new Darfur for communities and provide them with a road map on how they can be a part of that, then we can really bring about some change.

LAWTON: Chicago’s black churches have been particularly active. At Shekinah Chapel on a recent Sunday, the poetry ministry offered meditations on the crisis.

UNIDENTIFIED POET #1: This particular piece is dedicated to the hundreds and thousands of young girls who have experienced sexual violence as a means of ethnic cleansing.

UNIDENTIFIED POET #2: This is worse than a plague. This is cancer at its worst stage. This is genocide.

LAWTON: Shekinah and its pastor, Sean McMillan, joined with St. Sabina and churches across the spectrum in the successful Illinois divestment campaign. They are now lobbying for stronger national and international intervention in Darfur. They are also trying to expand their efforts even further within the black community.

Rev. MCMILLAN (Preaching): In all of the churches, all of the black churches across America this morning, how many of those churches talked about Darfur today? Wake up! You are dying, but nobody will stand up to a nation and say, “Let my people go.”

Rev. MCMILLAN (Preaching): In all of the churches, all of the black churches across America this morning, how many of those churches talked about Darfur today? Wake up! You are dying, but nobody will stand up to a nation and say, “Let my people go.”

UNIDENTIFIED PRIEST: Say “Peace in Darfur!” Say “Peace in Darfur!” Say, in the name of Jesus, “Peace!”

LAWTON: All of the churches involved say it is grassroots energy that will ultimately lead to change. I’m Kim Lawton reporting.