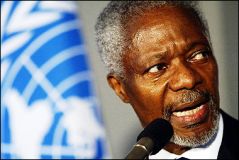

KOFI ANNAN : Africa cannot grow or be free on an empty stomach !

By KOFI ANNAN

Aug 29, 2005 (UNITED NATIONS) — Last Tuesday in Zinder, a town in one of Niger’s main agricultural regions, I met a 23-year-old woman named Sueba, who had carried her two-year-old daughter, Zulayden, more than 50 miles to reach emergency food assistance. Sueba had already lost two children to hunger, and her remaining child weighed just 60 per cent of what a typical two-year-old weighs. With a look I will never forget, she pleaded with the world to respond to her cry for help, not just today but in the months and years ahead.

Aug 29, 2005 (UNITED NATIONS) — Last Tuesday in Zinder, a town in one of Niger’s main agricultural regions, I met a 23-year-old woman named Sueba, who had carried her two-year-old daughter, Zulayden, more than 50 miles to reach emergency food assistance. Sueba had already lost two children to hunger, and her remaining child weighed just 60 per cent of what a typical two-year-old weighs. With a look I will never forget, she pleaded with the world to respond to her cry for help, not just today but in the months and years ahead.

The people and government of Niger are grappling with a devastating array of challenges, including hunger, prolonged drought, accelerating desertification, infestations of locusts and regional market failures. Government and civil society groups have now mobilised to deliver help to those who need it most. I saw profound suffering in Niger but I also saw signs that the country can come through this crisis, with lessons for all of us.

Niger’s struggle has belatedly galvanised international action. But a similar scenario of severe hunger and widespread food insecurity could still engulf some 20m people in other areas of the Sahel, southern Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and southern Africa. If the world acts now, this need not happen.

According to the UN World Food Programme, one in three Africans is malnourished. Each year, hundreds of thousands of African children die from preventable causes, most related to malnutrition and hunger. Human activities, poverty and nature are part of this lethal picture. In the Sahel, desertification and environmental degradation rob people of arable land and potable water, thereby increasing their vulnerability to food shortages. When drought followed last year’s massive swarm of locusts, the people were pushed beyond the brink.

We must address the problem of food security at its earliest stages, before suffering escalates. There is no silver bullet but there is much we can do.

First, better early warning analysis. Some of the international community’s early analyses failed to distinguish between “business as usual” – a poor country striving hard to meet its people’s needs – and the drastic emergency that the situation had in fact become. Some of the prescriptions that followed, therefore, did not reflect the urgency of the circumstances.

Second, enough advance funding to allow governments, the UN and non-governmental organisations to take adequate preparatory measures and deploy personnel with greater speed. One of the proposals I have put before next month’s world summit calls for a ten-fold increase in the UN’s Emergency Fund, which would enable UN agencies to jump-start relief operations.

Third, greater emphasis on prevention. Debt relief, increased aid and measures to make the international and regional trade systems more favourable to the poor can all help encourage local agricultural production. Increased use of irrigated agriculture could reduce dependence on irregular rains and boost food production. More generally, we need to draw on scientific advances and experience in Asia and elsewhere in order to trigger a green revolution in Africa. Prevention is always less expensive than cure. But when it is too late for prevention, because a crisis has already erupted, life-saving emergency aid cannot be subordinated to some future goal of self-reliance.

Fourth, a build-up of the region’s existing strengths and structures. The Economic Community of West African States has shown an increased ability to address the region’s humanitarian challenges and threats to its peace and security. The New Partnership for Africa’s Development offers an increasingly important framework for co-operation between African countries and bilateral or multilateral donors. Both merit greater international support.

Fifth, we must look in the mirror instead of pointing fingers. All the relevant actors – governments in the region, donors, international financial institutions and aid groups – share responsibility for the crisis. Each of us, in our own way, was too slow to understand what was happening, get people in place and come up with the necessary resources.

Our collective challenge is to alleviate unnecessary suffering, accelerate our response and strengthen local coping mechanisms to build a seamless, long-term approach to food security.

Africa cannot develop, prosper or be truly free on an empty stomach. Sueba, Zulayden and millions of their fellow Africans will never know true freedom so long as poverty continues to corrode human dignity. For their sake, and that of future generations,we must act now to end the scourge of African hunger.

The writer is secretary-general of the United Nations