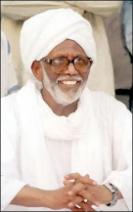

Portrait of Sudan’s “indestructible” Islamist leader

By Christophe Ayad

Feb 16, 2006 (PARIS) — Hassan al-Turabi, 73, Bin Ladin’s protector in Khartoum, and the source of inspiration for the international Islamist movement. Cast aside, he continues to theorize on a radical Muslim model.

“So, how are things in France? Am I still the devil in your country: Turabi, the ogre, the pope of Islamism?” The welcoming joke ended with a strange hissing sound, a mean dramatic laugh, teeth clenched, like Sylvester when he believes he finally has Tweety Pie within his claws. He seemed almost disappointed when the reply was no; he did not really scare anyone any longer; he had even been forgotten somewhat. Today, in the radical Islamist family, Hasan al-Turabi is the somewhat eccentric rambling grandfather. Turabi is not a selling point any more: too intellectual, too black, too sophisticated, too marginal. And then the Sudan is so far away, so complicated…

“So, how are things in France? Am I still the devil in your country: Turabi, the ogre, the pope of Islamism?” The welcoming joke ended with a strange hissing sound, a mean dramatic laugh, teeth clenched, like Sylvester when he believes he finally has Tweety Pie within his claws. He seemed almost disappointed when the reply was no; he did not really scare anyone any longer; he had even been forgotten somewhat. Today, in the radical Islamist family, Hasan al-Turabi is the somewhat eccentric rambling grandfather. Turabi is not a selling point any more: too intellectual, too black, too sophisticated, too marginal. And then the Sudan is so far away, so complicated…

We would be wrong not to pay attention to Hasan al-Turabi: the intellectual mechanism is as sparkling as ever. True, he is no longer the power behind the throne of the Sudanese regime, which used to invite every last one of the world’s Islamists to annual gatherings. They were all there, from the most radical to the most moderate: Americans from the Nation of Islam, Algerian members of the FIS (Islamic Salvation Front), Palestinian members of Hamas, Lebanese members of Hezbollah, radical Egyptians, as well as others, who, like Usamah Bin-Ladin, were less known but destined for a great future.

Banished from Saudi Arabia, deprived of his nationality, he found room and board, if not more, in Khartoum from 1992 to mid-1996.

“Usamah? I barely know him. I only saw him twice, including one time in my home. He was well integrated and accepted here but we saw little of him. His company won a contract to build a road to Port Sudan. The mistake was to have him sent to Afghanistan. There, without any nationality and isolated, he thought: ‘I have nothing to lose, everyone is against me.’ Had he stayed here, he would have done none of those things.” Bin Ladin also owned a large farm to the south of Khartoum, where he did not grow tomatoes…

Turabi has a selective memory: at the pinnacle of his power in 1996, he was the one who confided that “Usamah” was going to have to leave Sudan but that he could choose the destination and the time. His personal secretary discreetly established contacts for those who wished to meet him. And it was a young member of the Sudanese security service who acted as the “go between” [English in text], filtering requests for interviews and meetings.

“Usamah would not have done any of that….” Does this mean that he disapproves, condemns? Hasan al-Turabi fidgets in his pistachio green sofa. “I have nothing against the American people; they do not know anything about politics. It is the policies of America’s leaders that I am fighting because they want to dominate the entire world. When there is no freedom, this naturally provokes counter-violence. The violence sometimes exceeds legitimate limits.” What violence, what limits? We do not really know what he is talking about. He laughs again making his funny shrill sound. “How did democracy arrive in your country? It was through violence against the Old Regime.” Shrill noise again: “But who is Bin Ladin? He is someone who is not very well educated. It is the Egyptians around him who organize everything. He is merely a symbol who serves to mobilize spiritual energies; like Che Guevara, like Jeanne d’Arc. His propaganda, it is the media that does it for him for free.”

Ultimately, what bothers him about Al-Qa’idah is the lack of theoretical and political perspective. “Violence is not an end in itself. What worries me is that all the energy that is currently being exerted in the Muslim world is not leading to any theoretical work. Who is writing books? What is an Islamic government; and Islamic economy? Only Turabi is here to think about all that.” His age, 73, has not diminished his dandyism and even a kind of stylishness: manicured hands, small well-trimmed goatee, immaculate jellabayyah –a kind of loose cloak with a hood — light grey scarf, crocodile skin slippers….

When Hassan al-Turabi speaks of western democracy, he knows what he is talking about. He lived in France from 1960 to 1964, from where he returned with a doctorate from the Sorbonne. Still today, he takes pride in speaking very proper French, which earns him the sympathy, when it is not the admiration, of French diplomats posted to Khartoum. They owe him the delivery of Carlos, the terrorist, in 1994 in exchange for aerial photographs of the southern guerrillas…. Sometimes, he does not understand the way that France is heading. “Why the devil did France say “no” in the European Constitution referendum?” he says wondering. “That is something I do not understand.” Would a “yes” have been Islamist?

Turabi spent the next two decades going back and forth between prison and government. He is a champion in entryism and infiltration. In the early 1980s, he had already succeeded in convincing dictator Ja’afar al-Numayri, who had originally been rather to the left, to establish the shari’ah (Koranic law). In 1989, he carried out the perfect power hold-up by leading, from the shadows, the coup d’etat by young Islamist officers. Hasan al-Turabi still now denies that he inspired the “National Salvation Revolution”: “I was imprisoned like all the other politicians.” Except that he came out earlier than the others and he was not forced into exile.

Quite to the contrary, and this is where his secret reign begins. He had no official title but he led, with the support of young Islamist sans culottes, the “untouchables” of the very inegalitarian Sudanese society. Turabi, who is also from a modest learned family, knows something about this: only his marriage to a descendant of the Mahdi, a political-religious chief of the 19 th century, made him an “aristocrat”. At the time, Khartoum the African took on the look of Teheran: the Islamic veil slowly replaced the exceedingly transparent traditional thobe — an ankle-length garment with long sleeves, similar to a robe.

Alcohol was banned as well as parties. The press and the opposition parties were banned. Turabi also handled the slush fund filled with donations from Gulf shaykhs and put some of it aside, judging by his villa, which seems to come right out of the decor for the “Mon oncle” — My Uncle – by Tati — movie but which is furnished in a Louis Farouk style.

However, his revolutionary agitation ended up turning Turabi into a pariah. Mentor Turabi was betrayed in 1999 by two persons close to him: General Omar al-al-Bashir, the puppet he had made president, and Vice President Ali Osman Mohamed Taha, the most outstanding of his followers. They placed him under house arrest and then in prison. The taste of power and money – oil money was beginning to flow – got the better of the “revolution”. This cure out of government now allows him to distance himself from all the abuses of the 1990s. He has been free since July 2005, when a peace agreement between the north and the south went into effect, which put an end to two decades of civil war.

From his villa, Turabi continues to pull the strings on a guerrilla movement in Darfur, the turbulent province in the western part of the country that is plagued by a deadly civil war. He knows that the only way to return to the Sudanese political scene is to make the sound of guns heard. Turabi is a reflection of Sudan’s political class: indestructible. They betray one another, imprison one another, reconcile with one another, but they never assassinate one another. In Sudan, only the people have the privilege of dying.

(Liberation/translated by BBCMS)

The original text in French of the Portrait is available at http://www.liberation.fr/page.php?Article=359456