INTERVIEW- How to stop Darfur genocidical war

‘Khartoum will try corruption, coercion, force, anything’ to derail peace talks on the killing in Darfur, a Sudanese activist warns.

By Fareed Zakaria

March 20, 2006 issue — There is a glimmer of hope for Darfur, where in the past two years 300,000 people have been killed and 2 million displaced in a genocidal war that has been encouraged and funded by Sudan’s government. Last week the African Union declared a six-month extension for its 7,000 troops who are patrolling the region and protecting the camps for the displaced. In September, those soldiers may be placed under U.N. authority, which would mean a larger, better-equipped force.

International force is not a solution

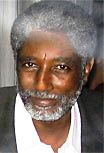

So why is Mudawi Ibrahim Adam not cheering? It’s not out of any sympathy for the Sudanese government, which has jailed him three times in the past 18 months, placed him in solitary confinement, confiscated his passport at one point and continues to maintain absurd criminal charges against him-including one that is punishable by death under Sudanese law. (It’s a Kafka-esque case: during one of his prison stays he carried out a hunger strike, and as a result has been charged with attempted suicide.) His persecutors want to scare him into silence. But they have failed. Mudawi continues to be an outspoken advocate of democracy and human rights in Sudan. He heads the Sudan Social Development Organization, a human-rights group that monitors the violence in Darfur and, in particular, has documented Khartoum’s role in funding, encouraging and assisting the genocide.

So why is Mudawi Ibrahim Adam not cheering? It’s not out of any sympathy for the Sudanese government, which has jailed him three times in the past 18 months, placed him in solitary confinement, confiscated his passport at one point and continues to maintain absurd criminal charges against him-including one that is punishable by death under Sudanese law. (It’s a Kafka-esque case: during one of his prison stays he carried out a hunger strike, and as a result has been charged with attempted suicide.) His persecutors want to scare him into silence. But they have failed. Mudawi continues to be an outspoken advocate of democracy and human rights in Sudan. He heads the Sudan Social Development Organization, a human-rights group that monitors the violence in Darfur and, in particular, has documented Khartoum’s role in funding, encouraging and assisting the genocide.

Even so, Mudawi isn’t clamoring for military intervention. “Simply putting more troops, or better troops in, is not much of a solution,” says Mudawi. “They will have some effect in lessening the violence, but only for a while. Look at what has happened with the African Union peacekeepers. At first they seemed effective, and within a few months they were being ambushed, having their jeeps stolen, and security got much worse.” Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick does not dispute that assessment. “The African Union forces have done a tremendous job,” he said last week. “But they came in to enforce a ceasefire, and that ceasefire has broken down.” The AU’s 7,000 peacekeepers-or even 20,000 U.N. troops-can’t be expected to control a region larger than France.

Political must be the solution

The conflict in Darfur arose from a series of political disputes between two groups: the Arabs who make up the government-backed Janjaweed militia versus the region’s non-Arab farmers. In 2002, the Janjaweed engaged in particularly bloody massacres, and the non-Arab tribes launched a rebellion against the dictatorship in Khartoum. The government responded by unleashing the Janjaweed, who since then have engaged in mass rapes, killings and lootings. Mudawi holds Khartoum squarely responsible for the atrocities. “The government of Sudan has taken advantage of political divisions … and is perpetrating crimes against humanity,” he says. Nevertheless, he adds, there’s no choice but to negotiate with the perpetrators: “The solution will have to be a political solution that addresses those divisions and, most important, that includes all the parties in Darfur.”

Darfur is not really represented in Abuja talks

Mudawi holds scant hope for the current peace talks in Abuja, Nigeria. “The parties from Darfur are not really represented,” he says. “The Khartoum government is there, but it has no interest in having the talks succeed. Relatively few of the Janjaweed or the other tribes are there. And no one is representing the 2 million people who have been displaced and are living in camps. They have separate but crucial claims that have to be placed on the table.” Mudawi wants talks with all major tribes represented. But, he argues, only the presence of a senior American figure at the table can offset the maneuverings of the Sudanese government. “Khartoum will try corruption, coercion, force, anything to derail such talks,” he says. “Only international pressure could counteract this.”

Peace in Darfur will certainly depend on talks between the groups who live there. Still, Mudawi and others who want an American at the table should recognize that the African Union and the United Nations might be more help. “If we’re out there front and center, the bad guys will discredit the whole process by presenting it as ‘American imperialism,’ another attempt at regime change and a plot to occupy another Muslim country,” says a senior administration official, asking to remain anonymous because of the talks’ sensitivity. “That will retard our efforts to stop the bloodshed.”

Could the people of Darfur really make peace after so much killing? “It happens everywhere,” says Mudawi. “In Sudan in particular, we know that we are a country of tribes. We have to live together.” After all, he says, decades of civil war in southern Sudan produced peace accords that are working now under the supervision of only a few dozen international monitors. Mudawi’s message appears to be getting through at last. He visited the United States last week and got a receptive ear from the administration. On Thursday he met with President Bush, and the president made sure they were photographed together. Bush wanted to boost the Sudanese dissident’s international visibility and send a warning to Khartoum. “I got the sense that Darfur is rising on the president’s agenda. And I think he understands there needs to be a broader solution,” says Mudawi. “I left the meeting with hope.” But as he well understands, it will take more than hope. Even doing good requires a plan.

(Newsweek)