UN rights mission treads fine line on Darfur

Feb 8, 2007 (GENEVA) — A UN human rights mission which is due to travel to Sudan’s strife-torn region of Darfur faces the conflicting tasks of proving its credibility and convincing Khartoum to lift any barriers, diplomats said here.

The assessment mission was set up by the 47-nation United Nations Human Rights Council in December after a tussle between western powers, and Khartoum’s African and developing country allies in the Council.

The assessment mission was set up by the 47-nation United Nations Human Rights Council in December after a tussle between western powers, and Khartoum’s African and developing country allies in the Council.

Officials said the mission hoped to travel to Sudan on Saturday.

However, a diplomat from the European Union cast doubt on the mission’s chances.

“Today we have no assurance that the mission would be accepted by Sudanese authorities,” the diplomat said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

After opposing western calls for a probe, African nations led by Algeria had sought a mission exclusively composed of Council diplomats, prompting a renewed clash with US and European countries over its independence.

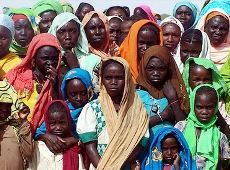

International aid agencies, human rights groups and African Union peacekeepers have reported more attacks in recent months on civilians in Darfur, where at least 200,000 people have died and more than two million have fled their homes.

The Council’s chairman, Mexican ambassador Luis Alfonso de Alba, said he had tried to placate critics on both sides of the fence by appointing a combination of activists and diplomats to carry out the probe.

The mission includes the outspoken former Nobel Peace Prize laureate and anti-landmines campaigner Jody Williams, a former UN deputy human rights chief, Bertrand Ramcharan, and the UN rights expert on Sudan, Sima Samar, who has been critical of Khartoum’s role.

Another member is Estonian parliamentarian Mart Nutt, who has taken part in Council of European human rights missions, while the diplomats are represented by Gabon’s ambassador to the UN in Geneva, Patrice Tonda, and his Indonesian counterpart Marakim Wibisono.

However, the decision to include diplomats from developing nations has annoyed western countries, who fear they might water down the independence of the mission.

The French ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, Jean-Maurice Ripert, said he was “surprised and disappointed” by their inclusion.

Ripert said the choice indicated that the UN’s top human rights assembly was still mired in its geopolitical rifts.

Meanwhile, diplomats said Sudanese authorities felt uncomfortable with Williams’ and Ramcharan’s presence and raised the possibility that their access might be restricted.

De Alba told AFP that the crossfire over the composition of the mission suggested that he had managed to strike a decent balance, and underlined Williams’s “uncontested moral authority” at the head of the group.

“This mission is not just about investigating the facts, but it also has a duty to build bridges between all the actors involved in the conflict,” de Alba explained.

“It must identify concrete action and contribute suggestions that will help bring about a solution,” he added.

UN monitors in Darfur are already reporting back about violations and attacks on civilians to High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour.

Sebastien Gillioz, of the campaign group Human Rights Watch, said the mission could add political weight to evidence of violations.

“The African Group has praised the peace agreement (signed by Khartoum) which so far is getting nowhere on human rights protection,” he said.

However, even if the mission meets the best expectations, the UN Human Rights Council will have the final word on the impact of its findings.

“They can come back with the best ever report, but the dynamics of the Council are such that it can be watered down,” Gillioz remarked.

(AFP)