FEATURE-On the road from Congo to Sudan

By Andrew Watkins

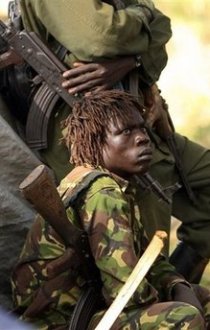

January 13, 2009 (YAMBIO) — Attacks by the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in recent weeks have increased in number and desperation following the tripartite Congolese, Ugandan and Southern Sudanese military operation against the group that began in mid-December. As a result of this action, codenamed ‘Lightening Thunder’, the LRA has been scattered and chased from its main stores of food and weapons in the Garamba forest of northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

What this has meant for the many civilians living in the border region between the DRC and Southern Sudan is increasing attacks. Many of these men, women and children have been forced to join a growing number of their countrymen and women moving north into Southern Sudan. On this journey, the main road connecting the villages of northern DRC with Sudan vividly display the truly desperate circumstances faced by many of these refugees.

What this has meant for the many civilians living in the border region between the DRC and Southern Sudan is increasing attacks. Many of these men, women and children have been forced to join a growing number of their countrymen and women moving north into Southern Sudan. On this journey, the main road connecting the villages of northern DRC with Sudan vividly display the truly desperate circumstances faced by many of these refugees.

Moving from northeastern Congo into Sudan, one of the first towns you encounter is Nabiapai. Located strategically on the DRC-Sudan border, the town operates a local market where Congolese and Sudanese traders work selling their goods and services. On Christmas day, LRA rebels ransacked the town stealing what could be stolen and torching the rest. Nabiapai no longer exists save for the ashen remnants of the lives destroyed there. Though one of the largest, Nabiapai was by no means the only village to face such a fate following the beginning of operation ‘Lightning Thunder’. Dozens of villages in northeastern Congo and Sudan’s Western Equatoria State met similar fates. Droves of people fleeing these attacks and others fearing pending ones rapidly began a sobering journey on the road into Southern Sudan.

From the border, the main road heads west to the town of Gangura some 10 km away. Here, refugees from Congo fuse with internally displaced persons from Sudan—particularly Nabiapai—to form a community some 2,500 strong. This makes Gangura the largest refugee camp of the nine hastily erected spaces lining the southern border from Sangua in the west to Nabanga in the east. The ubiquitous presence of a company of Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Army (SPLA) troops armed to the teeth betrays the serene, almost peaceful nature of the camp for the truly ferocious nature of the violence taking place around it. “We moved from Nabiapai after it was destroyed,” said one woman as she sat outside of the local Public Health Care Center (PHCC). Her feet swollen, each twice the size of a mango, she recalled the attack. “We all ran into the bush, we didn’t know where we were going and we couldn’t take anything with us.” She continued, “there is nothing there for us now and so we will stay here.”

While many wait in Gangura for the World Vision distributed, World Food Program (WFP) supplied food and non-food items, the UN has been unable to regularly access the areas along the road between Gangura and the state capital Yambio owing to insecurity. Threat level four, the highest level of alert in the UN and one that it has been operating under off and on since the attacks of mid-December, means that their teams remain confined to headquarters in the capital. Many here continue on the road towards Yambio. Twenty kilometers of water carved, axel-breaking road connects the two. Along the road passing through thick jungle bush and towering banana trees with their enormous green leaves, a steady procession of refugees and IDPs make their way north. Some use bikes, the majority travel on foot. “We come from Bitima in northeastern Congo,” said one group of over 40 refugees taking a short sojourn at a church along the road. “They told us we could stay here but that they couldn’t give us anything, we had to collect palm leaves as blankets,” said one of the groups elders. When asked where they were heading, an elder replied “we are very many so we would like to return to Congo but now it is not safe because of the attacks. I am not sure where we will go but for right now we will stay here.” Similar groups along this road, all facing parallel circumstances, have taken the same wait and see attitude. With no chance of returning home in the near future and difficulties in securing food, water and shelter while moving from place to place, many here have no choice but to make do with the little they can find. “At home I can feed myself but I’m not sure where the food will come from here,” remarked one woman as she traveled with her two young daughters north up the road. Many wish to stay along the border in hopes of returning to Congo to harvest their now dying bean and rice fields.

A significant problem faced by the relief agencies working in the area is that many of the refugees making their way up the road are simply being absorbed by members of their same Azande tribe who are spread in numerous small villages throughout the bush along the way. “At the stream ahead we will meet with the local chief and we will stay there until it is safe for us to go home,” said a group of men traveling north along the road. One carrying his clearly ill grandfather in an improvised box on the back of his bicycle lamented that even the sugar used for the man’s tea had been looted from their village during the recent attacks. Further up the road a group of women and children from the same DRC village of Bitima head for the same destination near the stream. The walk from Bitima to this village in remote Southern Sudan takes two days on foot, a voyage many here have made while carrying everything they now own. The majority Azande community here pre-dates the anachronistic imposition of colonial borders that took place in the mid-20th century prior to independence.

Those who do not stay at one of the villages between Gangura and Yambio continue up to Yambio, the Western Equatoria state capital. Here long settled Congolese refugees from previous conflicts operate businesses while newer arrivals look for welcoming members of family or tribe. “I myself have taken in a cousin from Bakiwiri in Congo and a niece as well,” explains George, a local gasoline distributor. “My aunt, two cousins and my niece were all working in Nabiapai and when it was destroyed, only my niece made it here. The rest are with the tong tong (the local term for the LRA).” George’s coworker Patrick had a similar story and had taken in a family member fleeing the violence along the border region. “This is Pascal, he made it here from Congo all by himself after Bakiwiri was attacked.” Speaking only French and local Azande, Pascal worked refilling local motorbikes with petrol as we spoke.

“There are many Congolese business here,” said Simon, a local beverage wholesaler in Yambio’s main market. “Many of those just arriving buy things and then take them into the smaller market to re-sell, they are the ones sitting on the ground with their items on sheets and blankets.” Some have set up businesses selling food adding a distinctly Congolese flavor to the Sudanese and Ugandan fare typically found throughout the state capital. Yambio however is not the final stop on this journey for many. Roughly 40 kilometers to the east over equally rutted roads is the settlement of Makpandu being constructed by the UN refugee agency UNHCR. The settlement was allocated a 20 sq km plot of land on which Congolese refugees could build permanent shelters for their families while the conflict continues to flare along the border to the south. Makpandu has as its genesis an agreement between UNHCR and the Sudan Reintegration and Relief Commission (SRRC) to settle the vulnerable refugee population away from the dangers of the border.

“We arrived on the 20th of September in Gangura but then the LRA attacked and so we moved here to Makpandu,” told one family living in one of the settlements transitional shelters meant to house them as they construct more permanent shelters for the future. “When they attacked we just ran anywhere, it was very frightening.” As he spoke, a small group gathered under the searing mid day sun, followed eventually by a crowd of nearly forty people. “We are given sorghum here but we can’t grind it because we have no grinders and our children wont eat it,” said one elderly man with few teeth and a large abscess on his left cheek. “Our family will build a garden next to our plot so that we can grow our own food,” remarked one emaciated looking man determinedly. “We feel safe here and that is good, but it is difficult that we don’t have enough cooking supplies and that we are not given food we are used to,” remarked one woman fresh from her third cigarette of the meeting. “There is not an adequate health center here,” one man remarked. “What happens if we get sick and need to go to the hospital?”

I posed this question about health care to a local NGO health worker that accompanied me to the camp to assess its medical capabilities. “They have no malaria medicine here, no oral-rehydration therapy, they can’t treat any type of deep lacerations and they will be out of antibiotics in three weeks at current usage rates,” she detailed. These usage rates were for the 154 people now living in the camp, rather than the 5,000 expected to make it home in the near future. Plus the local community health workers here, those who staff the PHCC, have not received paychecks in over two years thus necessitating that they take other jobs in order to make ends meet. “I work charting the different plots of land in the settlement for incoming families,” said Jashona, one of the health workers. “They don’t have my medicine in the center here and I need to travel to Yambio to get it from the pharmacy,” one disabled man explained as he sat near his tarp constructed permanent shelter alongside the PHCC. Off to the side stood another man, Emanuel, busily working to build transitional shelters for incoming refugees. “I was working in Nabiapai when the rebels attacked. I was with my niece at the time and we were separated, I have not seen her since,” he explained. “I will wait here for her and hopefully she will be ok,” he said as he banged away on one of the heavy teak posts used to erect the temporary structures.

The reality for those moving and living along this road is quite simply one of desperation and necessity. ‘When they came, we ran and now we can’t go back’ or ‘we are looking for food and a place to stay’ are the all too common refrains here. As the LRA attacks continue, more and more people will be forced into the often violent shadows of the unfamiliar, moving along this road towards the unknown.

(ST)