ANALYSIS: Sudan awaiting Mbeki’s panel report on Darfur

September 16, 2009 (WASHINGTON) — The Sudanese government is anxiously awaiting the recommendations by the African Union (AU) panel on Darfur (AUPD) hoping for a reprieve from its row with the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The report is expected to be released by the end of September, almost two month after the original deadline for completion of its work.

The report is expected to be released by the end of September, almost two month after the original deadline for completion of its work.

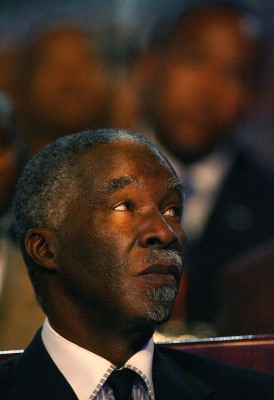

The panel headed by the former South African president Thabo Mbeki was established by the AU last February in response to the imminent issuance of an arrest warrant by The Hague based court for Sudanese president Omer Hassan Al-Bashir.

The AU has been critical of the arrest warrant asserting it will impede peace efforts in Sudan and in July African leaders endorsed a resolution halting any cooperation with the ICC on apprehending Al-Bashir specifically for states that has ratified the Rome Statute.

The mandate of the commission has not been made public but it is tasked with,

I. Conducting an in-depth assessment of the situation in Darfur since the onset of the current conflict, in particular as it relates to human rights and international humanitarian law violations and abuses;

II. Assessing the measures taken by the Sudanese authorities to address the human rights and international humanitarian law violations and other related acts committed in the Darfur region, including the role played by the Sudanese judicial system and law enforcement organs regarding the protection of the civilian population and the combating of impunity, in particular investigations of alleged violations and bringing their perpetrators to justice;

III. Assessing the level of the implementation by the Sudanese authorities of provisions of AU PSC decisions and UN Security Council resolutions relevant to civilian protection and human rights abuses and the extent of the cooperation extended in this respect to the AU Mission in the Sudan (AMIS), the Hybrid AU/UN Operation (UNAMID), as well as relevant UN agencies and other organizations;

IV. Assessing to what extent the issue of combating impunity, and promoting reconciliation, healing and peace has been addressed in the Agreements concluded by the Sudanese parties with respect to the situation in Darfur and steps taken or being contemplated to address this issue in the negotiations aimed at reaching a comprehensive and all inclusive peace Agreement in the context of the Darfur-Darfur Dialogue and Consultation (DDDC);

V. Examining the ongoing process initiated by the ICC in relation to combating impunity in Darfur and assess to what extent this process could affect the peace efforts underway in Darfur and in Southern Sudan, within the framework of the January 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), including the elections to be conducted in pursuance of the CPA, as well as its impact on regional peace and stability;

VI. Assessing the Sudanese judicial system and other customary mechanisms and procedures relevant to the processes of healing, reconciliation and compensation and to what extent they can be used to address the issue of human rights and international humanitarian law violations in Darfur.

Even though the AUPD is also looking at the peace aspect of the Darfur conflict, Khartoum is more concerned with the panel’s assessment of the Sudanese judiciary and its handling of the Darfur war crimes prosecution.

Ever since the UN Security Council (UNSC) referred the situation in Darfur in March 2005 to the International Criminal Court (ICC) on recommendation from the UN Commission of Inquiry, Sudan insisted that it is capable of trying the suspects itself and rejected the jurisdiction of the international tribunal.

The ICC has so far charged Bashir along with former Sudanese state minister for humanitarian affairs and governor of South Kordofan Ahmed Haroun, militia leader Ali Kushayb and Bahr Idriss Abu Garda, the leader of the Darfur United Resistance Front (URF).

All the suspects remain at large with the exception of Abu Garda who appeared voluntarily before the ICC judges on charges related to attack on AU peacekeepers in Haskanita in 2007.

Sudan vowed not to extradite any of its citizens to The Hague despite a Chapter VII UNSC resolution obligating Sudan to comply. The international community has been reluctant to address the issue in face of resistance by Sudan’s allies at the UNSC, particularly China and Russia, and other priorities related to deployment of peacekeepers in Darfur.

The Sudanese government had twice announced new judiciary initiatives to investigate Darfur right abuses. First in June 2005 when special courts were established by the Sudanese justice ministry, immediately after the ICC prosecutor formally opened an investigation into the situation in Darfur.

In August 2008, Sudan appointed a special prosecutor for Darfur crimes, weeks after the ICC prosecutor filed his case against Bashir with the judges for consideration. The move was also in response to pressure by the Arab League and other states on Sudan to prove seriousness in going after war crime suspects.

Furthermore, Sudan has announced that it has placed militia leader Kushayb, who is wanted by the ICC, in criminal proceedings for his role in several massacres allegedly committed in Darfur.

However, no prosecutions have emerged from these initiatives and progress reports submitted by Sudan show trials for minor crimes against few individuals.

An attempt by the special prosecutor Nimr Ibrahim Mohamed to probe Haroun was met with a fierce attack by the latter who said that any such move “is inconsistent with the state’s position on the ICC”.

This year, Sudan has adopted a new criminal law that added war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide into its penal code though it cannot be applied retroactively.

Sudan has also began taking a more hard-line approach towards any calls for further actions into Darfur war crimes prosecutions.

Last June, Sudan announced that it has rejected a proposal by the Arab League Secretary General Amr Moussa for further changes to the criminal law to incorporate more elements from the Rome Statute.

Sudan has also dismissed calls for hybrid courts comprising of foreign judges.

Furthermore, Sudanese officials including president Bashir in Zalengi last April began to downplay the importance of judicial prosecutions at this time saying that reconciliation should precede justice.

The justice minister Abdel-Baset Sabdarat said in an interview the same month that they are unable to go after suspects due to insecurity and instability in Darfur.

AUPD FINDINGS ON SUDAN JUDICIARY

The panel has met with Sudanese officials, rebel groups, Darfur IDP’s, political parties, civil society, lawyers and the ICC prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo.

Alex De Waal, a Sudan expert who is also an adviser to the panel, writes in his blog ‘Making Sense of Darfur’, about what they encountered in their discussions on justice with various parties they met.

De Waal gives examples of how the panel was initially met with intense skepticism on its impartiality by IDP’s and accusations that it is a cover up to protect Bashir from ICC prosecution.

This month, the major Darfur rebel groups in Darfur such as Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) led by Abdel-Wahid Mohamed Nur residing in Paris and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) have slammed the AUPD accusing it of being a tool to circumvent the ICC work on Darfur.

“The allegation that Pres. Mbeki was intent on salvaging Pres. Bashir came up several times in the discussion. One woman said, “We fear you are here to defend the criminal Omar al Bashir.” One man stood up and said, “Seven members of my family were killed. How should I feel if Thabo Mbeki says that Omar al Bashir should not go to court?” De Waal writes.

“Pres. Mbeki challenged him, “from where did you get this information that I said that President Bashir should not go to court?” The man responded, “it is well known.” He then said that the Africans were the ones saying Bashir should not go to the ICC, citing the early June meeting in Addis Ababa to discuss the African position on the ICC. This reply did not satisfy Pres. Mbeki, who continued to press him, “I asked you a question. Please answer it. You made an allegation. From where did you get this information?” The man said it was the BBC”.

De Waal said that “no one in Darfur was impressed with the performance of the Sudanese legal system, including the special courts”. The civil society provided a series of reasons to support that conclusion including the lack of seriousness on the part of Khartoum, executive interference in the judiciary and a culture of impunity “deeply implanted in the legal and administrative systems”.

However, some of those interviewed by the panel has called for a more traditional style of reconciliation, apology, blood money or even amnesty.

HYBRID COURTS?

In its briefings with the press and stakeholders, the AUPD gave no indication of what recommendations it will come up with except that to say that there is general agreement that justice must be done.

This month unidentified Sudanese officials said that Mbeki’s panel will propose formation of hybrid courts and appointing prosecutor.

Sudanese officials have pledged in the past that they will abide by any findings AUPD will craft. They hailed the work of the panel decribing it as a line of defense against “Western plots” namely the ICC.

Many observers say that Khartoum is optimistic that the panel will call for revoking the ICC mandate in Darfur and delegating it to local or regional courts.

This is to be in line with the declared position of the AU on the ICC arrest warrant for Bashir and mounting criticisms within the continent for the “unfair” focus by the court on African cases, observers say.

De Waal wrote in his blog emphasizing political limitations on the upcoming recommendations by the panel.

“There are certain realities, such as the positions taken by the AU heads of state, and by the ICC, which constrain and influence what the AU Panel can realistically recommend, but there are no overriding determinants on what it may decide,”.

A senior official at the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) in New York, who asked not to be named, told Sudan Tribune that he expects the panel to make a finding that the Sudanese judiciary “is unable and unwilling to carry out credible and genuine prosecutions in Darfur”.

“Based on what I know it is likely that the panel will recommend hybrid courts with the participation of Arab and African judges that conforms with international standards to try those not already charged by the ICC which means that Bashir and others will still have to answer at the Hague. Neither the panel nor the AU have the power to strip the ICC from its mandate particularly when Sudan has done little in that department,” the official said.

“I also expect them to call for a truth and reconciliation commission in Darfur,” he added.

Asked whether Sudan will be willing to implement the recommendations, the official said that the AU “is facing a credibility crisis”.

“Their [AU] stance on the ICC warrant for Bashir even though it was made under the rationale of preserving peace in Sudan, is seen by many worldwide as Africa condoning impunity,” he said.

“Mbeki’s panel has a challenge of proving its neutrality and the AU faces a similar challenge of pressing Sudan to get serious on going after human right violators at all levels of government,” he added

Sudan has recently renewed its push to campaign against the ICC particularly after the establishment of the ‘Group to Correct the Course of Darfur Crisis (NGCCDC)’.

Members of the group include individuals claiming to be former witnesses to the ICC and translators to Western organizations such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The group at a press conference in Addis Ababa said that some of its members have intentionally gave false information to these organizations inflating the death casualties.

NGCCDC called for rejecting foreign intervention in Darfur to avoid an Iraq-style scenario.

Sudanese officials expressed delight with the confession saying it proves “mass fabrication” campaign by the ICC and other groups to events in Darfur.

UN experts say 300,000 have died and 2.7 million been driven from their homes since rebels took up arms against Sudan’s government in 2003, accusing Khartoum of neglecting the region’s development. But Khartoum says 10,000 have died.

(ST)