Why confederation in Post-Referendum Sudan is key to prosperous, stable, and good neighbourliness

Why Confederation in Post Referendum Sudan is Key to Prosperous, Stable, and Good Neighbourliness between the North and South if South Chooses Independence?

By John Apuruot Akec

Two roads diverged in a wood, I took the one less travelled by, And that made all the difference – Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken. 1920.

November 17, 2010 — Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement, often abbreviated as the CPA, was signed between the government of the Republic of the Sudan (GOS) and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Sudan People’s Army (SPLM/A) in Kenyan town of Naivasha on 9th January 2005. The CPA was a materialisation of three years of sustained negotiations under the auspices of Inter-Governmental Draught Authority (IGAD), supported by the African Union, the Arab League, the EU, the UN; and the governments of Italy, Netherlands, Norway, United Kingdom, and United States. The signing of the CPA brought to an end Africa’s longest civil conflict in living memory that erupted in 1955, stopped for 13 years before resuming in 1983 and continued for 22 years until the CPA was signed in January 2005. The CPA is comprised of six protocols and three annexes and was recognised by the United Nation’s Security Council Resolution 1574. A central provision of the CPA is that the people of Southern Sudan have a right to self-determination which they will exercise by voting in a referendum scheduled for January 9th 2011, that is six (6) years after signing of peace agreement to decide whether to confirm the current status of united Sudan or secede to form their own independent state. The Machokos Protocols also obliged the two parties to the agreement to strive to improve institutional arrangements in order to make unity option attractive to people of Southern Sudan Furthermore, the parties to the CPA (the National Congress Party (NCP), and SPLM) are required by Referendum Act 2009 to agree on post-referendum issues such as citizenship (status of Northerners in the South and Southerners in the North), security, currency, distribution of oil revenues, national assets and foreign debts, and sharing of Nile water.

While there is concern that the referendum planned for 9th January 2011 is behind schedule because of deadlock over boundary demarcation, and continuing disagreement over voting eligibility of Messiryia in Abyei’s referendum; there is also a serious concern that no tangible agreement or coherent vision has yet been reached by the CPA partners on the nature of relationships between the North and the South in case of secession vote. This lack of vision regarding the form of future relationships between two parts of Sudan in post-2011 period, does cast enormous shadows of uncertainty over the future of both the North and the South, and makes it hard to plan for 2011 and beyond, especially amongst the government bureaucrats who are required to make vital decisions now and whose impacts go beyond January 2011. That is why we have commonly heard statements such as: “We do not know what will happen in January 2011”

It is quite certain that those making these statements know that referendum outcome will impact their plans and ongoing activities in many unpredictable ways, yet are almost helpless to craft an effective response to it. This is as if the world knew about Year 2000 problem, a built-in computer design constraint also called millennium bug that was predicted to cause date keeping system to malfunction when year 2000 arrives; thus, raising the risk of data loss; yet were unable to stop it or put in place measures to thwart its adverse impacts on business data and operation of vital and strategic utilities that are computer controlled. The truth is: the world knew its implications and acted by deploying large amount of resources and expert skills to fix the problem, and when the day and the hour arrived (midnight of December 31, 1999), everything was under control and no major catastrophes or financial losses were reported. The contrast could never be starker in case of Sudan in regards to post referendum arrangements.

The continuing uncertainty over the future relationship between the North and the South does not only make it hard to plan, but also makes it difficult for parties involved in negotiating post-referendum arrangements to make compromise on issues such as citizenship, residence and so on; as each party exercises ‘maximum precaution’ rule to guard its stakes. The two parties have been talking of good neighbourliness and peaceful secessions but no one knows what shape this good neighbourliness looks like, or how smooth secession can be achieved.

In fact, the lack of agreement on post-referendum arrangements, of which the North-South relationship is an important part, aggravated by inflammatory statements of Sudanese politicians across the divide, has caused mass exodus of South Sudanese from the North.

While Naivasha agreement has brought relative peace to the country after nearly quarter of century of strife and bloodshed, there is increasing realisation amongst significant Sudan watchers that the unity versus secession black or white dichotomy may not be the ideal solution for bringing about a lasting and sustainable political

accommodation in Sudan.

Most recently, there has been increasing interest in confederation as one of potential options for closing the gap in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement without sacrificing the right of people of South Sudan to determine their own political future.

John Garang de Mabior, the SPLM chairman, proposed a system of confederation for Sudan during peace negotiations in Kenya between 2002 and 2005 but was turned down by National Congress Party (NCP). The deputy SPLM chairman and current governor of Blue Nile State, Malik Agar Eyre floated the idea in Naivasha peace celebration on 9th January 2008 for the whole country. This time around the NCP expressed readiness to discuss it with SPLM. A number of articles followed in sparse succession. For example, confederation was impressed upon the CPA partners in May 2009 in an informative article by Adullahi Osman El Tom of Justice and Equality Movement as one of potential options for post-referendum governance of Sudan in case South Sudanese vote for independence. In January 2010, Hamid Ali El Tigani wrote in Sudan Tribune about confederal system for Sudan.

Overall, these early calls to debate confederation seemed to have fallen on deaf ears and did not take the headline or get the attention the subject deserves. At that time, 2011 seems to be far off, and any talk of confederation was seen as an attempt to subvert the exercise of right to self-determination by South Sudan. However, this author noted that the interest in confederation was rekindled once again after publishing an article on the subject in June 2010. Ever since, there has been a growing interest in confederation as a ‘third way’ between total unity and complete independence of the South. At the same time, many voices expressed reservation,24 even outright rejection of confederation as a substitute for complete independence of South Sudan25,26,27. This reflects the old adage: information too early is not recognized, and information too late is useless. Now is the right time to fully explore the potential of adopting confederation and encouraging the partners to the CPA to give it more serious attention than it is currently receiving.

The paper will examine why this is an invaluable strategy for both the North and the South to adopt in short term as a mechanism for achieving a smooth transition of the South to independence in case of secession, and in long term as a means for propelling the two parts of Sudan back into a path of voluntary unity or economic integration. It will also attempt to answer such questions as: What chance there is that such an idea will find acceptance from South Sudanese? Who will be against it? Who is for it? What is there in it for each stakeholder (SPLM, NCP, Northern and Southern parties)? And what are the parties to the agreement doing about this option at the moment, if any? And finally to look into what structure the North-South confederation might take as well as possible powers can be assigned to confederate authority. However, the paper will not necessarily follow the same order.

THE JUSTIFICATION FOR ADOPTING CONFEDERATION

In a symposium organized by Future Trends Foundation and UNIMISS in Khartoum on unity and self-determination in November 2009, Francis Mading Deng argued in a joint paper with Abdelwahab El-Affendi:

“Unity should not be seen as an end in itself or as the only option in the pursuit of human fulfillment and dignity. A vote for Southern independence, therefore, confronts the nation with challenges that must be addressed constructively in the interest of both North and South. This should mean making the process of partition as harmonious as possible and laying the foundation for peaceful and cooperative coexistence and continued interaction. Practical measures should be taken to ensure continued sharing of such vital resources as oil and water, encouraging cross border trade, protecting freedom of movement, residence and employment across the borders, and leaving the door open for periodically revisiting the prospects of reunification.”

This statement underlines the need to come up with concrete measures to address the challenges enlisted above. Here Deng attempts to persuade the unionists in Sudan to let the South decide freely, and that they should never have to loose hope in unity even if the referendum outcome is secession. Vital interests of the South will dictate her to seek cooperation of the North. He correctly puts his finger on the pulse, and leaves us with the challenge of prescribing practical measures that we need to take in order to achieve the above goals.

Independently reflecting on the necessity of letting the South go as the necessary condition for paving a way for voluntary unity in the future, this author wrote in November 2009:

“The way forward would be to honour the CPA referendum protocol in its entirety, despite the predictable outcome. Namely, more than 90 percent of South Sudanese will vote in favour of self determination. Yet paradoxically still, only after the South peacefully secedes will we have the hope to renegotiate a Sudanese union on new basis. We must let the sheep out of the fence, then persuade them later to re-enter the stable after having tasted the freedom of wandering the pastures alone with no one but good own self to guide through the treacherous valleys, tr[ied] the beauties as well as the pains of self-reliance, miss[ed] the advantages of a shared-house where all have something different and unique to offer…In other words, Southern session is a necessary prelude to voluntary reunion.”

This author perhaps was then led subconsciously or (was it an Eureka moment?) to end at confederation gate when he argued:

“Once South is secure in self-determination, which in many ways will satisfy a deep-rooted psychological longing and restore a sense of dignity long lost, it will be possible for all to revisit the possibility of entering into economic union similar to EEC’s with the North or reach confederal arrangements with the rest of the country with a view to eventually reintegrating back in a phased out fashion.”

This might be too an optimistic a scenario and overstatement by this author, because it is possible for the two parts of Sudan to still drift apart even after a secession vote should relationships continue to be tense and hostile as they currently are, or the way they had been in the last five years. Yet, this fear of unknown should not scare the Sudanese from taking the bold step towards confederation after Southern secession vote because we have previously tried many things and nothing seemed to work.

And in that spirit, and after serious self-reflection the author wrote an article in June 2010 inviting the Sudanese to debate adopting confederation as a means of regulating South-North relation after referendum should South secede as it is likely it will:

“And in humble contribution to shaping of this vision [about possible relationships between North and South], the writer of this article would like to invite all the Sudanese to air their views on feasibility of adopting confederation to manage the North-South relationship when South votes for independence.”

The article went further to propose the possible structure the confederation might

take:

“”According to this vision, both South and North will be free to organise their foreign policy, security, and economic planning as would happen for all sovereign states. The current council of states and national legislative assemblies will have their life extended (funded by Confederation to 4 years) and functions of certain national commissions will be modified to support confederal government. There will be a Northern Chamber, where Khartoum government can discuss issues concerning the North. The merits of a monetary union should be carefully studied and given a serious consideration in this debate. The management and sharing of common assets and regulating trade should be managed by the confederation whose presidency rotates every 6 months between the South and North. Citizens from both Northern and Southern states will be free to move freely and enjoy the full rights of the citizenship (education, medical treatment, right to buy and sell property) in two Sudans. Both Sudans should device tariffs that will not put any side at disadvantage and maximise the accrued benefits for all. Fighting crime and managing security across the borders is carried by confederal government in collaboration with the two sovereign states. This confederal arrangement will constantly be improved and renewed every 4 years (equivalent to life of legislative assemblies) and the renewal should be voluntary (each side can opt out at the end of 4 years should it feel there are good reasons to quit).”

A natural question that impresses itself upon this debate is: what is unique about confederation to make it an effective tool for political accommodation34 in Sudan in the event of South Sudan vote for independence to the exclusion of everything else?

A well presented and most comprehensive technical report published so far on the subject of potential options for political accommodation between the Northern and the Southern states in the event of secession vote has been authored by Gerard Mc Hugh of Conflict Dynamics International. The report enlists four (4) possible options organised in order of increasing political interactivity between Northern and Southern sovereignties with distinctly recognisable international identities. These are described in the proceeding paragraphs.

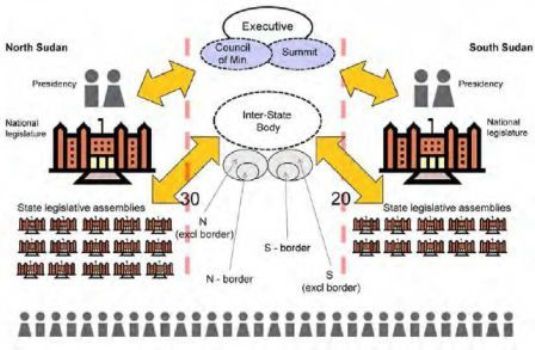

The first option is described as Mutual Isolation. As its name suggests, this option entails a very limited scope of political interaction. This is a default option if no effort is made to agree on common institutions to deal with issues of common interests. It is recipe for disaster and is ill suited for case of Sudan where there are issues that need to be jointly addressed through much tighter interaction than can be garnered from this option. The second option is Reciprocity between Independent States. It allows the two independent states to either interact on issues of common interest on ad hoc manner as they arise or set up single institutions within each state through which the interaction on economic and political matters can be channeled. Considering the high stakes between the North and the South, one is bound to bypass this option in favour of searching for better institutional arrangements that are commensurate with the stakes involved. And moving up higher, there is third option modelled as Economic Community of Independent States. The main objective of such interaction is economic and to a lesser extent political. The scope of economic parameters is agreed between two sovereign states with provisions of summit meetings of heads of the states and councils of ministers. Legislative bodies in the two states also interact and there is legislature to regulate the interaction that is embodied in their respective constitutions. In this author’s view, this is the minimum required of political accommodation in the North-South relations if South secedes. And finally, we have Structured Union of Independent States. Here the two sovereign independent states agree to set up common institutions. The competencies of the inter-state bodies are formally agreed between the two states. Interactions include meeting forums between heads of states and a council of ministers appointed by heads of independent states. The common institutions are manned by representatives of the two sovereign independent states whose task is to take decisions on issues of common interest that are identified from time to time jointly by the two sovereign states. Decision-making in inter-state bodies is based on parallel consent while at the executive levels (summit of heads of states, and council of ministers), decisions are based on unanimity. This option is seen to provide the highest degree of political accommodation between the North and South Sudan. One version of Union of Independent States is shown in the figure below.

The choice of the model of interaction between North and South Sudan independent states should put into consideration the following elements in regards to arrangements

for political accommodation:

– Should not interfere with or compromise the political independence of South Sudan;

– Should strive as much as possible to implement the principle of right of self-determination of the people of South Sudan as embodied in the CPA, as well as observing the equal right to self-determination of other people in the Sudan;

– Should neither subordinate nor supersede executive-level authority in North or South Sudan;

– The associated frameworks for political interactions should reflect all relevant provisions agreed in the CPA without necessarily being constrained by the CPA;

– Must be able to accommodate the needs of Southern Kordofan, Abyei, Blue Nile, and other areas;

– There must be equity of representation and effective checks and balances in place to ensure parity (for North and Sudan) in political decision making in the shared/common central institutions

From a personal point of view, a confederal arrangement scores highly when measured against the listed guidelines.

One definition of confederation is given below:

“Confederation is a system of administration in which two independent countries enter into [union] while keeping their separate identities. The countries cede some of their powers to a central authority in areas where they share common economic, security, or broadly speaking, developmental concerns. The central authority in confederation is weak and subservient to the founding states. It cannot dominate and can only exercise powers that are ceded to it by the con-federal partners. While confederation is a perpetual arrangement, either of the partners can pull out of it if they so wish. Hence, confederation is like marriage; it takes two to create and maintain but only one partner to dismantle. Confederation comes in different forms depending on the contexts and interests of partners involved.”

Fig. 1 Schematic Illustration of Structured Union of Confederal Sates (Source: Gerard Mc Hugh, Envisioning Sudan: Options for Political Accommodation between North and South Sudan Following Referendum, Publication of Conflict Dynamic International, September 2010).

WHAT ARE CHANCES THAT CONFEDERATION WILL BE ACCEPTED BY THE SOUTH?

At official level, SPLM leaders have been dismissive of the idea. Publicly, they have maintained that there will be relationships with the North in case of secession and especially in regards to four (4) freedoms: movement, ownership, residence, and employment. This was confirmed by the First Vice President of Sudan, and President of Government of South Sudan, Salva Kiir Mayardit, in one of a series of exclusive interviews with Rafayda Yassen of Al-Sudani newspaper that was published beginning on 27 October 2010 and continued for a number of days. According to Salva Kiir, as far as it depended on his government “the people [of North and South Sudan] will be free to work, live, and move and pay visits to friends and relatives in the North and the South, and that the presence of the borders will be meaningless.” In a recent interview with the Sudani daily newspaper, Asked of what he thought about “a third way” between unity and separation, Kiir responded:

“I do not know about any other third way between unity and separation other than confederation. And if that is what is meant by the third way, it does apply in the context of two sovereign independent states, as opposed to one and same country. Hence, let our focus be on making sure that referendum takes place on time on 9th January 2011 so that South Sudan can exercise the right to self-determination. If the choice of the South is secession, only then will it be possible for us to enter into negotiations with the North about confederation, and if we both agree [on confederal arrangement], each country will [also] have its own constitution and own government.”

Responding to the recent proposal by Egypt to the government of Sudan to consider confederation as one of post-referendum arrangements regarding the relationships between the North and the South in case of secession of South Sudan, the SPLM Secretary General and Minister for Peace and CPA Implementation in the government of South Sudan, Pagan Amum, rejected the call for confederation and instead appealed to “all to work towards timely conduct of referendum and recognition of the outcome and that in case of Southern secession they will be ready to agree any form of relationships that will serve the interests of the North and the South and maintain peaceful coexistence.” Now who will doubt that SPLM leadership is organised (or united) as far as their official position is about confederation?

It is worth pointing out (as previously mentioned in the introduction of this paper) that confederation was initially proposed by SPLM far back in Abuja negotiation in 1992, then in Machokos in 2002, and later by Malik Agar on third anniversary of death of SPLM Chairman John Garang de Mabior in January 2008. These earlier proposals were rejected by the NCP, but when raised again in 2008, the party expressed its interest to discuss confederation with the SPLM. And since full independence is of ‘higher value’ than confederation in which South must concede some power to the an inter-state authority, it is not surprising to see SPLM reluctant to warm up to reincarnation of the idea in the 11th hour. Intuitively it is like taking two steps backwards.

And as far as public opinion was concerned in the South regarding confederation, it was either dismissive or received the proposal with great skepticism, while asserting the full exercise of right to self-determination by the South. For many South Sudanese, the call for confederation was a distance thunder, until president Thabo Mbeki, the Chairman of African Union High-Level Implementation Panel shocked everyone with the unexpected announcement when he put confederation on the table as one of four (4) post-referendum options the CPA partners must consider during launching of post-referendum negotiation in Khartoum in July 2010. Here, Mbeki proposed to the parties to consider negotiating on one four (4) post-referendum options: unity, separate states requiring citizens of successor and predecessor states to get visas, independent states with soft borders and thus no strict visa requirement, and two sovereign independent countries joined up by a confederate union.

Some of the skepticism amongst South Sudanese to confederation proposal made by Malik Agar and version being placed on the table by president Mbeki is due to the confusion that confederation is being put forward as a substitute for secession in the referendum options or a substitute for the whole exercise of self-determination.50 That means, if it is explained clearly that the referendum will go on as scheduled and result recognised, then people in the South may be prepared to consider the idea. That does not mean there are no Southern separatists who regard confederation as a new tactic by the unionists in Sudan supported by the NGOs and international community with vested interests.51 And admittedly, some of writings were emotive, Southern nationalistic, and devoid of reason, yet not surprising at all. Consider the excerpt from a poem published on internet condemning the unionists and proponents of confederation amongst South Sudanese: Unity is a mamba snake, Unity is a thoroughfare to Golgotha A trap door of a gallows Does the South deserve the guillotine? Beware of Jallaba [Northerners] mendacity Confederation is a ticket to Armageddon A camouflaged lure to uninterrupted misery

If anything, this is a reflection of the deep rooted mistrust which South Sudanese hold against their fellow countrymen in the North for historically well documented injustice. It was this kind of well founded cause for disappointment that prompted the veteran Sudanese statesman, Abel Alier, to write his well known book, Southern Sudan: Too Many Agreements Dishonoured. To overcome this mistrust would require exceptional statesmanship in both North and South in order steer the people of Sudan through these turbulent times to the shores of peace, stability, prosperity, mutual trust and understanding between the citizens of Sudan.

And despite the widespread reservation, there are bright spots of positive response to the call for confederation in post-referendum Sudan if South secedes. For example, consider this quote:

“A confederation is not a bad idea because it answers some tough questions that we cannot answer under unity-separation-only model. But this confederation will only be an option if South Sudanese have chosen to be a different country in 2011. The confederate government will give both the North and the South a bigger market that we desperately need in the world of today.”

As a follow up to an earlier contribution,55 this author has argued elsewhere that confederation is a good strategy for South Sudan to tactically choose secession and then enter into a confederal arrangement with the North and be ready give up some of its oil revenue to the North to improve its chances of building its new nation in peace and stability, and that the South should not see secession as an end itself, but rather as a means to attaining freedom.

HOW DOES NORTH SUDAN FEEL ABOUT CONFEDERATION AS A BETTER FORM OF SECESSION?

At official level, there is clear readiness to discuss confederation as previously mentioned in the paper. For example NCP leaders have been positive to recent proposal by Egypt regarding confederation. The wisdom that loosing one limb is better than loosing two applies to the NCP led Khartoum government which would rather not take all historical responsibility for splitting up of the country into a Northern and Southern independent states. No easy answer as to why NCP rejected confederation when it was initially proposed in Abuja in 1992 and Machakos in 2002. We may get some clues when Egypt invited SPLM and NCP to discuss post-referendum arrangements in June 2010, the two parties locked horns trying to trade secularism against Islamic Sharia constitutions.

An NCP insider and former minister of finance and economic planning in the central government, Abdel Rahim Hamdi, made some bold if blunt recommendations to the government regarding North-South relationships in event of secession vote in a workshop organised in Khartoum by Faisal Islamic Bank. The former finance minister called for normalization of relationship with the South in event of secession, opening up of North-South border, and provision of four (4) freedoms: movement, employment, ownership, and residence. He also advised the parties to the CPA not to tie borders demarcation with referendum, and called for formation of economic union between the North and South Sudan with inter-state institutions to manage the relationships between two independent states.

On the academic front, a number of researchers and political experts called for a constitution to regulate the relationships between the predecessor and successor states; maintaining that since it is highly likely there will be a secession vote, there is no need for the government to conduct referendum but should declare South Sudan independence inside the National legislative Assembly. They also called for open borders, and a summit of heads of states; that there must to be equal representation in inter-state bodies. They also proposed that decision-making in inter-state bodies be by unanimity.

At the level of political parties, both Umma and DUP parties support confederation as alternative to full secession. The National Popular Party leader, Hassan Al-Turabi dismissed the recent Egyptian proposal of confederation as “valueless and arcane” in an interview with Al-Sharq Al-Awsath.

At a popular level, a new campaign organisation named Movement for Assertion of Rights and Confirmation of Citizenship has been formed in Khartoum. It is calling for dual nationality for Southerners in the South and Southerners in the North and four (4) freedoms for all the citizen in the North and the South.

THE STANCE OF INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY IN RESPECT TO CONFEDERATION

The international community is concerned about the lack of a road map that clearly addresses vital post-referendum arrangements that include the nature of North-South relationships capable of tackling the unresolved outstanding political issues such Abyei referendum, management of oil and water resources, demarcation of North-South border, and the citizenship rights of the soon to be independent neighbouring states, movement and ownership of property, among others. Many analysts have expressed doubts about practicality of South Sudan seceding without making compromises in regards to sharing of oil revenue, and reaching a framework agreement on institutional cooperation with the North.

This concern caused the head of AU panel, president Thabo Mbeki to propose confederation to the CPA partners as one of viable post-referendum options in event of South Sudan secession by encouraging them to consider forming: “two independent countries which negotiate a framework of cooperation, which extends to the establishment of shared governance institutions in a confederal arrangement.”

President Mbeki also reminded the NCP and SPLM of the changing times, saying: “In the 21st century, the world has changed, and especially Africa has changed. No nation is an island sufficient unto itself. The African Union is itself an expression of the African continent’s desire for integration and unity.”

The US Secretary of State, Mrs. Hilary Clinton, warned the international community to do more in preparation for January 2011 and described the referendum process as a ‘ticking time bomb’, given that the outcome is more likely to be in favour of Southern secession. She prodded the South to agree some accommodation for the North to reduce the chances of a renewed conflict.

President Barrack Obama in his September 24 New York Meeting of UN Security Council underlined his concern for Sudan’s future when he said: ” What happens in Sudan in the days ahead may decide whether a people who have endured too much war move towards peace or slip backwards into bloodshed. And what happens in Sudan matters to all of sub-Saharan Africa, and it matters to the world…”

What’s more, the Egyptian foreign minister last week made a proposal to two the CPA

partners (SPLM and NCP) to consider confederation in the event of Southern secession.

The UK Secretary for International Development, Mr. Andrew Mitchel, stressed in his visit to Sudan this week that he discussed with the government officials the importance of holding referendum on time and setting up “cooperative institutions after Southern secession.”

All this expressed concern demonstrates the importance the international community attaches to reaching a formula for political accommodation in the North-South relations before the referendum takes place, for everyone’s peace of mind.

THE ECONOMICS OF SECESSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR NORTH AND SOUTH RELATIONS

Seventy five (75) percent of Sudan’s 6 billion barrel proven oil reserves is found in the South. Transportation and sale of oil takes place through the North. Ninety eight (98) percent of the revenue of the government of Southern Sudan comes from oil revenue. When South Sudan secedes, the government of Sudan will loose fifty (50) percent of its oil revenue. There are 1.5 million Southerners with families living in the North. 6 million Northern nomads spend 8 months in a year in the South Sudan in search for pastures and water for their livestock. Unquantifiable number of South Sudanese travel to the North for medical treatment. There are a large number of Northern traders in the South. Northern Sudan needs South Sudanese labour in construction sector and other productive industries. At least fifty (50) percent of academic staff in Southern Universities is comprised of Northerners.

What all this shows is that the economic interests between the North and the South are too intertwined to be sorted successfully by any system of political accommodation except through structured and institutional cooperation between the Northern and the Southern states.

This paper has assumed that referendum will take place either on time as scheduled, or after some delay. It has addressed itself to highlighting the reason why confederation between the North and South has the potential of achieving the needed political accommodation necessary for sustainable peace and prosperity between the North and the South in case of Southern vote for independence. As Sudan and the international community prepare for referendum in January 2011, it has become very apparent to all that agreeing on a number of post-referendum arrangements can speed up the process and could result in a more acceptable outcome for all, leading to recognition of the result if South Sudan votes for independence as is being predicted by analysts and opinion polls.

The ruling party in the North (NCP) is suspected to be playing delaying tactics in order to score as many concessions as possible from SPLM which is the ruling party in South Sudan and cosignatory to the CPA. Moreover, one suspects that the NCP is reluctant to take full moral responsibility for splitting up of the country and thus is looking for a face-saving grace. On its part, instead of taking the lead in making the necessary compromises, SPLM is fearful of its political popularity and future in the South Sudan and hence decided to follow the public mood, wherever it might lead. That is, SPLM is doing things right as oppose to doing the right things.

Moreover, confederation, as far as Southern opinion (SPLM included) is concerned, is akin to taking one a step forward and two steps backward. This, in SPLM view, may unnecessarily be giving a moral victory to NCP, which will likely jump up to claim wining the ‘battle for unity.’ On the other hand, by dragging its feet in honouring the Hague ruling on Abyei’s border and putting countless obstacles in the way of completing the referendum, the NCP is deepening mistrust and blowing away any chances of South Sudan considering a confederal arrangement with the North. Given these seemingly insurmountable political obstacles, it appears at the surface as if the current deadlock cannot be broken to pave way for a break through.

The psychological scares for those who will be affected by South and North going their ways without proper institutional arrangements to resolve problems and address issues that are common in nature to the two Sudans, specially in transition zone, are too grave to calculate or quantify. For example, Messyria tribe depend on NCP to defend their interests. People of Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile states are thriving in the shadows of SPLM protection. And when the SPLM uproots and moves southwards as it were, its shadows will move with it, and thus jeopardizing the livelihood of those who depend on its presence in the union.

Yes, confederation gives some, albeit superficial moral victory to NCP which it needs in order to safe its face, but does not compromise the independence of South Sudan. On the NCP side, it should try to honour what it has agreed to without hesitation even if it has to take some hard decisions like what Ariel Sharon had to do with the Jewish settlers in the West Bank when he forcefully removed them to honour Israeli pledges to Palestinians. This confederation should initially be renewable over, say four years, after which its performance may be reviewed by the North and the South. It should be internationally recognised and supported with guarantees.

This will not entirely remove the risk of a renewed conflict in the future and may not stop a fervent arm race between the South and the North. It need not be too troublesome if the two Sudans modernize their armies to keep security or create deterrence against war mongers on both sides.

There is no slightest doubt that confederation is the missing link in Sudan’s referendum puzzle. It creates a win-win situation for all people of Sudan, with the South taking most out of it than it can do with separation-only paradigm. While allowing the South to satisfy long held yearning to determine its future, it does so without doing away with historical, economic, and cultural ties with the North. It also absorbs any adverse effects that would result from splitting Sudan after more than a century of coexistence with all its imperfections. An initial agreement or a guaranteed signal in that direction will go a long way in easing the rising tensions. The promised four (4) freedoms the CPA parties have been touting are better served under confederate arrangement. Thus, it rests on the international community to encourage the parties to the CPA to make a bold move towards striking a deal on future confederal arrangements.

Symbolically, Sudan will still be united; that is, united more by mutual interests as opposed to history, prestige, or birth rights. Practically, there will be two independent states cooperating and complementing each other’s economies; each bringing into the union its comparable advantage.

The author is Vice Chancellor of the University of Northern Bahr El Ghazal, Sudan.

This paper was presented by the author at a conference organized by St Antony’s College, Oxford University under the theme “Post Elections Governments of Sudan: How are they preparing for a Referendum on Self-Determination?” on 13th November 2010.

jur_likang_a_ likan'g

Why confederation in Post-Referendum Sudan is key to prosperous, stable, and good neighbourliness

Your idea is outdated and unwanted. I think it is wrong to sell such an idea. Do not set ground for Arabisation and Islamisation in South Sudan. We need a liberal, democratic, federal sovereign state in Juba that has ambassadorial relationship with the North.