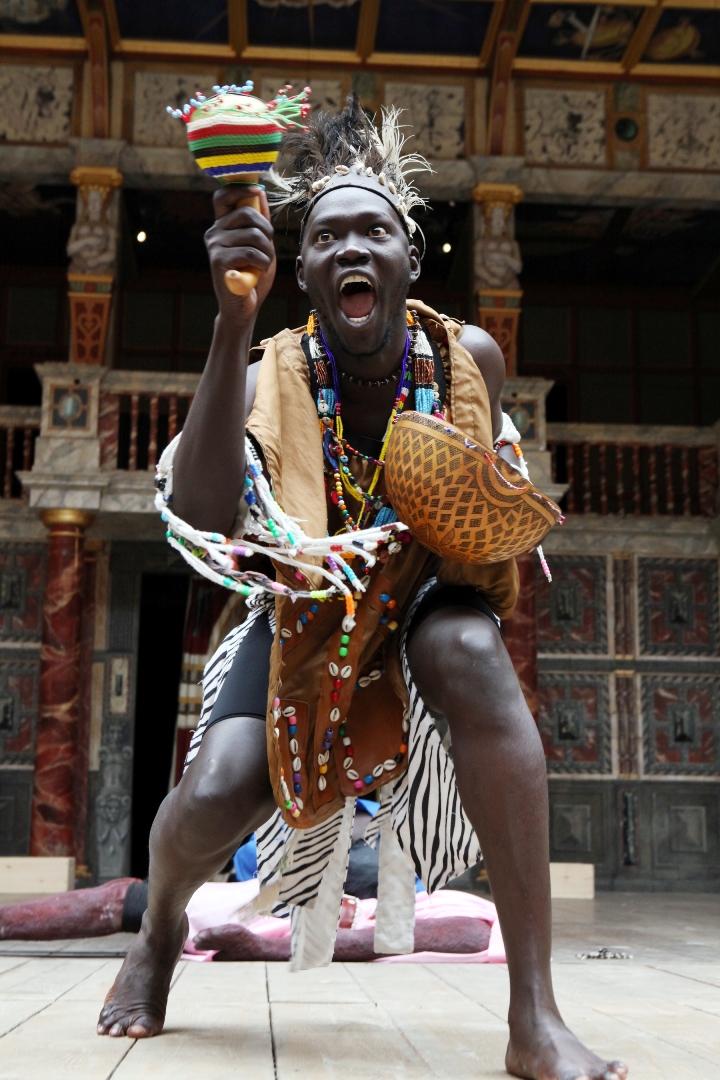

South Sudan Theatre Company perform Cymbeline in London

By Toby Collins

May 9, 2012 (LONDON) – The South Sudan Theatre Company (SSTC) has received glowing praise for their performances of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline in London’s historic Globe theatre.

As part of the Globe to Globe festival South Sudanese actors and production team travelled to London to perform the play in Juba Arabic, in the reconstructed home of Shakespearian theatre.

An international audience gave the South Sudanese a warm reception.

Giving it four out of five stars, the Guardian said of the performance, “The world’s youngest nation seems delighted to be here and, played with this much heart, even Shakespeare’s most rambling romance becomes irresistible.“

Sudan Tribune spoke to the production’s translator, Derik Uya Alfred, and director, Joseph Abuk, on Saturday.

Uya said they chose Cymbeline because of the parallels between its conflict between Britain and Rome, and the Sudanese civil war which ended in 2005, leading to the independence of South Sudan in 2011.

In Cymbeline a peace agreement is similarly reached and a process of mediation is carried.

With conflict between Juba and Khartoum flaring up once again, the play’s content is all the more pertinent.

The production was executed by people from all over South Sudan. “The beauty of art is that it is not a simple thing which is segregated; art is a unifier,” said Uya.

“We are people with a new vision. We have brought all of South Sudan before a mirror to smile at itself,” he added.

The displacement and loss of life during Sudanese civil wars has affected the South Sudanese cultural identity, explained Uya, “a treasure has been thrown into the sea; not a sea that can allow recovery.”

Some of the youth from the Diaspora have scant knowledge of the traditional songs and dances of their homeland. The engagement of all South Sudanese with these cultural practises is imperative in the process of fortifying a homogeneous sense of cultural identity in South Sudan and therefore, nation-building, he explained.

The SSTC performance incorporated traditional song and dance, which received a very positive reaction from the audience.

Despite Juba Arabic being incomprehensible for much of the audience, the strength of the actors performances made the course of the action and their emotional responses to it, clear. This was aided by screens displaying scene synopses.

Despite Juba Arabic being incomprehensible for much of the audience, the strength of the actors performances made the course of the action and their emotional responses to it, clear. This was aided by screens displaying scene synopses.

There were points at which only the Arabic speaking part of the audience laughed, but for the most part, the audience was united

Abuk explained that the Globe was an appropriate venue for their performance “because we come from a society where when something happens, people crowd around it.” The Globe a rebuild of the theatre in which Shakespeare staged his plays.

In Shakespeare’s time the actors would have been contending with a far more raucous audience including thieves and prostitutes which would have drowned out many actors. However the SSTC’s performance was robust and above all, entertaining. Brought back to its home after passing through the cultural filter of South Sudan, Cymbeline felt at once new and true.

At the Globe the majority of the audience is standing and can touch the stage. There is therefore a very strong sense of interaction between the performers and the audience, which the SSTC actors capitalised on, addressing audience members directly and in one case, upon hearing news of his wife’s infidelity, holding hands with a member of the audience for consolation.

The audience included people from north and South Sudan; “it is very difficult to create enmity with art. If you like it, you clap for it,” noted Abuk.

With regards to the public relations value of the successful performance, Abuk said that South Sudanese are often portrayed in the media as children with bloated stomachs and flies around their eyes, and that “today there were no flies.”

As well as filling the South Sudanese audience members with pride, the performance created an invaluable buzz about South Sudan, which was acknowledged by the South Sudanese minister for culture, Cirino Hiteng Ofuho, who has now put theatre at the top of his agenda, said Abuk.

“If we can use art in nation-building, in no time we can conquer tribalism and corruption and create positive values,” added Abuk, hopeful that the arts in general will be given greater credence in the political sphere.

Abuk mentioned South Sudanese musicians who are currently flying their country’s flag abroad: Emmanuel Jal, Ruth Mathiang, Emmanuel Kembe, and Gordon Kong. He explained that although their music is contemporary, it still has a South Sudanese identity, borrowing from traditional rhythms and languages and “saying something good about South Sudan.”

“We have been quiet for a long time. We will surprise the world,” said Abuk.

AUDIENCE REACTIONS

Elizabeth Yol, who has lived in the UK for over two-decades after fleeing the civil war told Sudan Tribune immediately after the final performance that “words will never explain the way how I felt today. I really really feel that I have been represented.”

She said it was the “first time for us as the Southern [Sudanese] to come to Great Britain” and express the new country’s identity and culture.

The play was a “combination of the culture of the South, its all there […] I am so happy to have a country,” she said.

Amal Ajang, another South Sudanese refugee who fled to the UK during the civil war said that watching the production had made her “feel free” for the first time.

“For the first time we can present something about our country, about our identity. Because all these years our identity has been suppressed; only the identity of the Arabs has been presented on the TV. So it is nice for the world to see some people from South Sudan,” said Amal.

She said that the play depicted “our culture and our identity” and was a metaphor for South Sudan’s “struggle” from oppression of Khartoum’s governments for over half a century. “In the end after how many years, we have become a free nation.”

Mohammed Ansari who works for the Arab League in London said that it was “really a very beautiful day. I felt that still we are one country I enjoyed it very much.”

Mohammed who studied at the University of Juba, while it was based in Khartoum said that the actors were “very confident” and acted in a very professional way, especially interacting with the audience and making them feel “part of the action.”

(ST)

Additional reporting, Tom Law.

Audio

International Insights from the Globe Theatre Website

Video