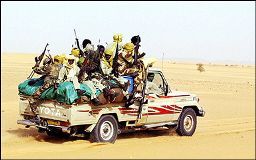

Darfur rebels hold out in remote camps

By Emmanuel Braun

CORCHA CAMP, Sudan, Aug 19 (Reuters) – Abdul Karim Abdalla pounds the earth with a metal cane in a rebel camp in western Darfur, passionately imploring his fellow fighters to defend the land of their fathers from Arab invaders.

Abdalla, who is about 50 and dressed in a T-shirt and trousers, is putting the 350 men based at this remote camp near Sudan’s border with Chad through their daily paces.

Abdalla, who is about 50 and dressed in a T-shirt and trousers, is putting the 350 men based at this remote camp near Sudan’s border with Chad through their daily paces.

The camp is in a natural clearing shrouded from the harsh sunlight by six towering trees. The men, some wearing yellow turbans, some baseball caps, and many swathed in magic charms, sit on wooden benches holding a hotchpotch of rifles.

They are members of the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), one of two rebel groups in Darfur which took up arms in 2003. They say Khartoum has spurned this vast region, where African villagers vie with nomadic Arab horsemen for meagre resources.

Since the fighting started, an estimated 30,000 people have been killed and more than a million driven from their homes, mostly into camps dotted across Darfur and neighbouring Chad.

“The Arabs are trying to divide us. But Darfur is our land and the land of our ancestors. We must defend ourselves,” says Abdalla, after showing the men how to hold their guns as they launch a mock attack.

For the rebels, marauding Arab horsemen known as the Janjaweed are the enemy. The rebels say they are based at a camp along with government soldiers some 10 km (six miles) away.

“In (peace talks in Chad) we asked the government to collect weapons from the Janjaweed and now they continue to attack us and our villages,” said Khamis Abdalla, the SLA commander here, adding that the camp was attacked in July.

JANJAWEED

Abdalla, who keeps in touch with SLA leaders with mobile satellite phones and listens attentively to news broadcasts on the BBC in Arabic, said the group would go to another round of peace talks due in Nigeria next week.

“We are not ready to talk about political issues as long as the government will not collect weapons from the Janjaweed,” he said holding a report on the Darfur crisis by the International Crisis Group.

“We are going to tell the African Union and the European Union (in Abuja) that the Sudanese government is still attacking us. If they stop and collect weapons, we are ready to talk politics,” he said, a thick scar visible on his upper arm.

The Sudanese government has about two weeks left before the expiry of a U.N. Security Council deadline demanding that Khartoum shows it is serious about improving the security situation in Darfur or face unspecified sanctions.

In the area around the SLA camp, most villages are deserted. The inhabitants have fled to Chad after Janjaweed raids and towering grass all but hides the straw huts with conical roofs.

The rebels have a few horses but no vehicles so they move on foot, stopping to drink by scraping holes in dried-up river beds to suck up the water hidden below the surface.

At Gundo, a two-hour walk from the camp down dirt tracks hidden in the rampant undergrowth, an old lady is the sole inhabitant left after a February attack.

Hawa Oumar says it’s too late to move now and she would prefer to die in her village.

A young girl, Nadifa Abakar Ismael, brings Oumar food from a settlement a couple of hours away. But it’s not without risk. She says she stumbled across three Janjaweed five days ago.

“They fired at me but they missed. They just hit my dress,” she says, showing where she had patched up the hole.