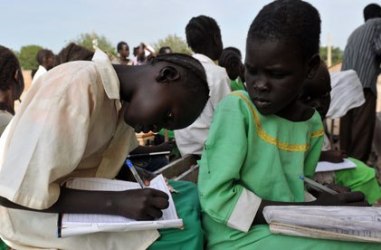

FEATURE: Marriage quashes education hopes of S. Sudanese girls

January 14, 2016 (TORIT) – It took years of pleading before Jane Aketch persuaded her parents to send her to primary school in the dusty bush of Magwi, a remote area in South Sudan’s Eastern Equatoria state.

“Generally, in South Sudan, girls are supposed to stay at home and clean, while boys attend school,” says the 14-year-old, the eldest of five children.

Aketch said her sisters all dropped out of school before completing their primary education.

“My parents didn’t approve of us going,” she said, shyly looking away.

Yet boosting education was vital in developing South Sudan after it attained its independence on July 9 2011, following January’s referendum on secession, which was part of a 2005 deal that ended two decades of civil war.

40 percent of girls in sub-Saharan Africa reportedly marry before the age of 18, and African countries account for 15 of the 20 countries with the highest rates of child marriage.

Schooling is poor across the board in South Sudan, an overwhelmingly rural region. There is only one teacher for every 1,000 primary school students and 85 percent of adults do not know how to read or write.

For girls and women, it is even worse. UNESCO, the United Nations’ (U.N.) educational and cultural organization, estimates that nine out of 10 women in the world’s youngest nation are illiterate.

South Sudanese parents keep their daughters away from school for many reasons. Sometimes, it is a reluctance to send girls to mixed-gender schools. More often, a girl is considered a source of wealth to her family for the “bride price” or dowry she brings upon marriage, and so is married off at a young age.

In some communities, an educated woman who carries a pen rather than a bundle of firewood is considered a disgrace and by virtue of her education may attract a lower dowry.

“I was married off at a very tender age,” recalls Rosemary Atong Ajith.

“My parents were given so many cows by my husband. Up to now, my younger sisters are not allowed to attend school,” she added, “They are often told to follow my example.”

Although the tradition of paying “bride price” is ancient, many South Sudanese women are now calling for the practice to be abolished.

Other major obstacles girls face in gaining an education include sexual harassment, early pregnancy and child-to-child, according to a 2008 study by the United Nations (U.N.) children’s agency UNICEF.

The study, based on findings from UNICEF’s 2006 Rapid Assessment of Learning Spaces, also raised concerns about poorly educated and trained staff handling expanding class sizes, limited supervision at county and state levels as well as low motivation causing teachers to quit the profession.

According to UNICEF, an estimated 340,000 children were enrolled in primary schools at the time Sudan’s 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed. In 2009, however, primary school enrolment reportedly reached 1,362,941, with about 860,000 boys and 502,000 girls. Less than two percent of them, UNESCO says, complete primary school education.

The US-based Human Rights Watch, in report released last month entitled, “Ending Child Marriage in Africa: Opening the Door for Girls’ Education, Health, and Freedom from Violence,” indicated how child marriage has dire lifelong consequences, often severely reducing a girl’s ability to realize a wide range of human rights. Marrying early often ends a girl’s education, exposes her to domestic and sexual violence, increases serious health risks and death from early childbearing and HIV, and traps her in poverty.

“Government leaders across Africa often say the right things about child marriage, but have yet to produce the political commitment, resources, and on-the-ground help that could end this harmful practice”, it said.

Meanwhile, UNICEF estimates that without progress to prevent child marriage, the number of married girls in Africa will rise from 125 million to 310 million by 2050. In September 2015, African leaders joined other governments to adopt the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include a target to end child marriage in the next 15 years.

Also, Africa’s human rights treaties on women’s and children’s rights, agreed to by African states, explicitly state that the minimum age of marriage should be 18. As such, on November 26 and 27, the African Union held the first African Girls’ Summit on Ending Child Marriage to highlight the devastating effects of child marriage, call for legal reform, and share information about good practices.

Other continent-wide initiatives, including the campaign to end child marriage, which began in 2014, and the appointments of an African Union special rapporteur on child marriage and of a goodwill ambassador for the African Union Campaign to End Child Marriage, are all steps in the right direction, but could be more effective with better coordination, Human Rights Watch said.

South Sudan is reportedly among the few African countries that have shown that the absence of comprehensive national strategies on child marriage and poor coordination among government ministries and agencies undermines the effectiveness of government efforts.

“There is no single solution for ending child marriage,” said Human Rights Watch.

“African governments should make a commitment to comprehensive change that includes legal reform, access to quality education, and sexual and reproductive health information and services,” it recommended in a recent report.

Currently, many African countries have multiple legal systems, in which civil, customary, and religious laws overlap and in many cases contradict one another. Traditional beliefs about gender roles and women and girls’ subordination underlay many customary practices, such as payment of a dowry or bride price, which perpetuate child marriage.

At least 20 African countries, according to Human Rights Watch, allow girls to marry below the age of 18 through their minimum age laws or exceptions for parental consent or judicial approval. Weak enforcement has meant that there has been little impact even in countries that have established 18 as the minimum age of marriage for both boys and girls.

Poor access to education can also contribute to child marriage. When schools are too expensive or distant or are of poor quality, many families may pull their daughters out, leaving them at greater risk of marriage. Inadequate water and sanitation facilities can deter girls from attending school, especially once they begin menstruating.

“Governments should set the minimum age of marriage at 18 and make sure it is fully enforced, including by training police and officials who issue marriage certificates,” said Agnes Odhiambo, a researcher at Human Rights Watch.

“Since government officials can’t bring about change alone, they should work with religious and community leaders who play an influential role in shaping social and cultural norms,” she added.

Complications resulting from pregnancy and childbirth are is reportedly the second-leading cause of death globally among girls ages 15 to 19. The stress of delivery in other cases can cause obstetric fistulas, a tear between a girl’s vagina and rectum that result in constant leaking of urine and feces and girls suffering this condition are often ostracized by their families and communities. Child marriage exposes girls and young women to violence, including marital rape, sexual, domestic violence and emotional abuse.

(ST)