Defining genocide defies agreement

By APARNA H. KUMAR, Associated Press Writer

WASHINGTON, Aug 23, 2004 (AP) — Two years after Winston Churchill called it “the crime without a name,” a Jewish lawyer who had fled the Nazis dared to give it one. He called it genocide.

More than 60 years later, it’s not the crime that is debated, it’s the name.

More than 60 years later, it’s not the crime that is debated, it’s the name.

In Darfur, an arid stretch of western Sudan, 30,000 African villagers have been slain by nomadic Arab militiamen. In the past month, the number of refugees has jumped 20 percent to 1.2 million, according to the United Nations. As the rainy season peaks, relief workers are warning conditions could rapidly deteriorate.

But world powers, including the U.S. government, remain divided over what to call the crisis in Darfur. The U.S. State Department is expected to decide soon whether it is genocide.

The debate runs deeper than semantics because the label comes with a weighty question attached: If it is genocide, what is the world going to do about it?

U.S. President George W. Bush has called Darfur one of the “worst humanitarian tragedies of our time,” U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell dubbed it a “humanitarian catastrophe,” and both houses of Congress, on July 22, voted to declare it “genocide.”

Eight days later, the United Nations Security Council threatened “measures” against the Sudanese government if it does not take steps by the end of August to end the conflict. The resolution avoided the words “sanctions” and “genocide.”

The European Union, the Arab League and the African Union have also not called the crisis genocide.

Raphael Lemkin coined the word in 1943, from the Greek word genos, for race or tribe, and the Latin word cide, meaning killing. Genocide gave definition to a whole category of “acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.”

Its legal definition was coded in the 1948 U.N. Convention on Genocide, signed by virtually every nation and binding them to “prevent and punish” the crime. Acts of genocide include killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, mass rapes, expulsion and other actions aimed at destroying the group. The United States enacted the convention in 1988 and Sudan joined it in January.

The Security Council resolution, drafted by the United States, condemned violations of human rights “by all parties to the crisis, in particular by the Janjaweed (Arab militias), including indiscriminate attacks on civilians, rapes, forced displacements and acts of violence especially those with an ethnic dimension.”

In a guest column in The Wall Street Journal on Aug. 5, Powell said, “Regardless of the words used to describe what is happening in Darfur, we are acting with the utmost sense of urgency.”

Nevertheless, a U.S. State Department team is interviewing Sudanese refugees in neighboring Chad to determine whether the atrocities that led them there constitute genocide or ethnic cleansing, in which the intent to destroy a group cannot be established.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Agency for International Development has warned that the death toll could surge to 350,000 if aid doesn’t reach some 2 million people soon.

Kristin Wells, counsel to the House Judiciary Committee, said the congressional resolutions declaring genocide in Sudan were “a political strategy” to prod the Bush administration to use leverage with other countries to do more.

“The view on Capitol Hill was that the point of the 1948 convention on genocide was to prevent genocide,” Wells said. “What’s the point of having a special word if it’s just for the history books?”

Four U.S. Congressmen have gone further to draw attention to the issue. Democrats Charles Rangel, Bobby Rush, Joseph Hoeffel and Albert Wynn have been arrested for protesting outside Sudan’s embassy in Washington. Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, a Republican, declared the situation genocide after visiting refugees in Chad earlier this month.

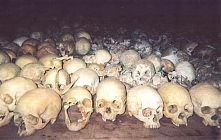

Many human rights advocates point to the past cases of Rwanda and Bosnia.

In the early 1990s, some 250,000 Bosnians were killed by Serbian forces. In 1994, in Rwanda, more than 900,000 people died during a conflict between the majority Hutu tribe and minority Tutsi tribe.

In both instances, the first Bush and Clinton administrations stopped short of calling the killings genocide.

“How many people should die before they call it genocide?” asked Amal Allagabo, a Sudanese immigrant in Virginia who said she does not know if many relatives in Darfur are alive or dead. “Are they waiting for Rwanda to happen again?”

Yet even if genocide is established, the Genocide Convention did not set a threshold for action or spell out what such action should be. It said only that nations could call upon the United Nations to take “appropriate” measures.

The Bush administration helped broker a Sudanese cease-fire in April and wants African nations, now monitoring the agreement, to send their own peacekeepers. The United States is the largest donor of humanitarian aid to Darfur, having pledged $299 million through next year.

Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry says the government-sponsored atrocities in Sudan “should be called by their rightful name genocide.” His campaign said he would consider military force, but not as a first step.

Even within Amnesty International, there’s a debate about whether to call the crisis genocide.

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, on the other hand, declared the crisis in Darfur a “genocide emergency,” something it has not done before in its 11-year history, said Jerry Fowler, director of the museum’s Committee on Conscience.

“When there’s a strong case that something is genocide, then we can’t be afraid to use the word,” he said