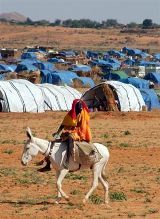

Animals eat but humans hungry in Darfur camp

By Opheera McDoom

RIYAD CAMP, Sudan, Sept 26 (Reuters) – As the last few days of the rainy season subside in Sudan’s conflict-torn region of Darfur, the green grasses make rich fodder for donkeys and cattle.

But some 10,000 people in this refugee camp in the outskirts of the rundown capital of West Darfur state say they remain hungry. They squat, waiting — for help that may never come.

But some 10,000 people in this refugee camp in the outskirts of the rundown capital of West Darfur state say they remain hungry. They squat, waiting — for help that may never come.

“We are waiting for the United Nations to come with their forces,” said Ayoub Ismail. “If they don’t come, we will go to Chad.”

But the United Nations is not sending peacekeeping forces to Sudan’s remote west, where about 1.5 million people have fled their homes. Already, some 200,000 refugees are encamped in the impoverished desert expanses of neighbouring Chad.

Ismail has been in the camp since last December, after he said he fled attacks on his village by government planes, helicopters and mounted Arab militias, known as Janjaweed.

Riyad camp is about 35 km (20 miles) from the Chad border. Ismail says the only reason he and the others have not already left is because the roads are not safe from Janjaweed attacks.

Yvan Deret from the Triangle aid agency says the last food distribution in Riyad was in July and there were riots as rations were assigned only for just over 4,000 people, when the camp actually houses about 10,000.

The U.N. refugee agency says food for another 4,000 people was later distributed. A food ration is usually meant to last four to six weeks.

“The conditions are harsh,” Deret said. “There’s no really accurate estimate of the numbers here.” He said Triangle and two other aid agencies were trying to assess the true figure.

A new, more accurate survey should be completed in two weeks, he said, which would allow more adequate food portions.

“We are just hungry. The world is sick. We sit here and they give us nothing,” said Halima Ahmed, who fled her village nine months ago.

NO GOING BACK

Deret said a major problem was the camp’s proximity to the state capital Geneina, as residents who housed many refugees had now run out of food but do not qualify for help from aid agencies.

“They are said to be cheating, but this conflict affects many people,” he said.

As the hot sun beat down upon their heads, women and children crowded around a visiting delegation of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, Ruud Lubbers, asking for food.

“They bring us water, but we need food too,” said Usmi Khali, 35. She said she would never go back to her village, which the militias burned nine months ago.

After years of skirmishes between Arab nomads and African farmers, two rebel groups launched a revolt last year, accusing Khartoum of arming Janjaweed to drive non-Arabs off their land.

Khartoum denies the charge, calling the Janjaweed outlaws.

“I’ll not go back. Never — they will kill us all,” Khali said, nursing her arm, which she says the Janjaweed broke in three places when they attacked.

Ahmed said she had nothing to go back for. “Why would I go back? There’s no food, no water, no people — it’s empty,” she said, declaring she would never leave the camp.

Many of the makeshift shelters did not have plastic sheeting to withstand the heavy rainstorms that are usual in Darfur at this time of year.

“We need sheets — we sleep and insects eat us,” said Fatma Ibrahim, showing maggots she said ate into her body at night.

Some people said there were still attacks on people in the camp. Ayoub Ismail said armed men in uniform came in the previous night and raped a woman in her house.

But many of the women said they felt safe inside the camps, but were afraid to go too far outside in case they were attacked.

Aid officials working in the camps said there were reports of attacks, but it was difficult to tell who was responsible, as the traumatised refugees now called everyone Janjaweed.

“There’s nothing to ensure physical protection of the camp,” Deret said.