Refugees returning to Sudan’s Darfur find region still in turmoil

By ELLEN KNICKMEYER, Associated Press Writer

SULIEAH, Sudan, Sep 27, 2004 (AP) — Sudanese officials drove up to the creek near the Chad border where Alama Abdullah Hassan was hiding with her family three months ago: “It’s safe now in Darfur. You can go home,” Hassan recalls their saying.

On Monday, Hassan was tending two young girls, a daughter and a cousin, curled up in pain from gunshot wounds, and mourning two female cousins — all victims of an armed raid that the African village family blames on the pro-government Arab Janjaweed militia on Sept. 22.

On Monday, Hassan was tending two young girls, a daughter and a cousin, curled up in pain from gunshot wounds, and mourning two female cousins — all victims of an armed raid that the African village family blames on the pro-government Arab Janjaweed militia on Sept. 22.

Most international officials and Darfur civilians say bombing blamed on Sudan’s government in 19 months of Darfur conflict has stopped. Sudan, under threat of U.N. sanctions over Darfur’s crisis, insists it is now doing all it can to calm the situation and says it is ready to welcome home the region’s 1.4 million uprooted non-Arab African villagers.

But the few who do trickle back are finding a countryside in violent flux — with steady raids blamed on both Arab Janjaweed militia, non-Arab African rebels and simple banditry, and whole villages and tribes on the move in search of safety — and finding it nowhere.

“There’s no security here, if we could go back to Chad, we would,” said the 35-year-old Hassan, who, with her extended family, had taken the Sudanese officials at their word and returned to her home region in July.

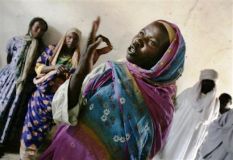

In the two-room bare concrete hospital clinic around her, villagers newly returned from refugee camps across the border in Chad or hiding places in strange villages, creeks or mountains of Darfur spoke Monday of threat from near-daily attacks that all blamed on the Janjaweed.

“I myself came home yesterday from Chad. I wanted to see my family,” said Bishara Ahmed Terab, from the village of Cosimo.

In that space of time, Terab said, he had already seen a man shot dead by the Janjaweed, Terab said.

Many of the attacks start with cattle raids, and many of the attacks are tied up with traditional tribal conflicts that have been going on generations before Darfur’s conflict broke out in February 2003 and gained international attention in recent months.

The United States, European Parliament and others accuse Sudan’s government and allied Janjaweed militia of genocide in a campaign of burning, raping and killing that has claimed more than 50,000 lives.

The bloodshed broke out with an uprising by two non-Arab Darfur rebel movements, who attacked primarily government installations and military targets to press demands for a bigger share of power and resources for Darfur.

On Monday, a helicopter flight across Darfur showed abandoned villages scattered among the herders and farmers of still-thriving communities. Some villages appear to have been recently vacated, their neatly tended walled compounds of round mud huts and peaked thatched roofs empty of people and animals. Other villages are overgrown with weeds, apparently deserted before the just-ended rainy season.

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, Ruud Lubbers, said violence continues in the region.

“They declare a cease-fire, but I don’t see people coming home,” Lubbers told aid workers during a visit to a camp for displaced people across a field from the village of Seleah. “There are still incidents.”

“Regularly,” said Jo Mason of the Irish relief group Concern, one of the international agencies at the camp.

“Regularly,” Lubbers agreed.

Sudanese Social Affairs Minister Habib Makhtoun told Lubbers and reporters on Sunday that Darfur’s conflict is a problem of tribal clashes and bandits.

The government is investigating attacks as they occur, and arresting culprits when it can, Makhtoun and other Sudanese officials said.

Aid workers in government-held territory in Darfur blame raids and attacks on both the Janjaweed and by Darfur Sudanese Liberation Army rebels, including those now based across the border in Chad.

Plus “traditional tribal conflicts,” Mason said. In the international view of Darfur, “everything’s being combined, but it’s not — you have to distinguish between Janjaweed attacks, SLA raids, and traditional conflicts.”

Villagers here who fled a combination of alleged Sudanese bombing raids and Janjaweed attacks a year ago now say the government, at least, is no longer attacking them.

“At least there are a lot of army and soldiers here,” said Terab, newly returned from Chad. “If there is protection here, I will stay. If not, I will go.”

At the Seleah clinic, Hassan’s cousin, Abakar Ali, lay with sheets covering a leg with seven bullet wounds in it from the Sept. 22 attack.

When he gets better, he plans to return home, despite the two years of violence that have killed his brothers, sisters and cousins.

“Because home is better than any place,” Ali said.