Blair issues list of demands on “terrible” situation in Darfur

KHARTOUM, Oct 6 (AFP) — British Prime Minister Tony Blair left Sudan after securing promises from Khartoum to heed a list of demands to alleviate what he said was the “terrible” situation in the war-torn region of Darfur.

|

|

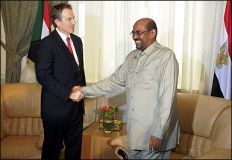

Sudanese President Omar el-Bashir (R) shakes hands with British Prime Minister Tony Blair (L) at the presidential palace in Khartoum in Sudan.(AFP) |

Flying into the capital early Wednesday, he headed straight into talks with President Omar al-Beshir and First Vice President Ali Osman Taha before calling for a peace agreement to cover the whole of Sudan by the end of the year.

Blair, who underwent an operation to correct a heart flutter just five days earlier, told a press conference he had issued a list of five demands aimed at ending the 20-month-old conflict and humanitarian crisis in Darfur.

“We want the government to commit to reaching a comprehensive agreement, north and south, in Sudan by the end of the year,” Blair said, referring to the multiple ethnic rebellions dogging the Arab-dominated regime in Khartoum.

And if progress is not made, “the pressure remains on” at the UN Security Council for sanctions, Blair told reporters as he sweltered in 40 degree Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) heat in the garden of the British embassy.

“All of us have watched over the past months with concern and alarm to the death, the disease, the destruction that has come to Darfur, and the terrible humanitarian situation that has arisen as a result,” Blair said.

He called for a major boost to African Union forces in Darfur, which currently number just 300 in a region the size of France, and more action by Khartoum to create the security and other conditions to allow aid to reach the estimated 1.4 million people displaced by conflict.

He also called for the identification of all government troops and militia, and an agreement by the rebels to stand down their fighters, as part of an overall peace deal for Sudan.

A 21-year-old uprising by rebels of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army in the mainly Christian and animist south is Africa’s longest-running conflict.

The Beja community in the east and the minorities of the Nuba mountains in the centre have also spawned rebellions, while the main opposition parties in Khartoum established an armed wing after they were banned by Beshir’s military-backed regime.

Blair said the fact he had travelled to Khartoum — the first ever visit to an independent Sudan by a serving British premier — showed “the seriousness with which this is taken”.

Following the talks, the Sudanese foreign ministry said the government had committed itself to meeting certain demands on improving the situation in Darfur.

That contrasted with a statement from an official travelling with Blair who said: “They have agreed to all the prime minister’s five points.”

The foreign ministry statement did not mention such crucial issues as disarming pro-government militias or bringing them to justice.

It did say the Sudanese government was committed to a “peaceful resolution to the Darfur conflict through negotiations and dialogue.”

It said Sudan and Britain had expressed full commitment “to the leading role of the African Union and its contribution towards resolving the situation in Darfur” and agreed to “expand the AU observer mission in Darfur”.

It also pledged that Khartoum would “cooperate and abide by the resolutions of the AU and the Security Council” regarding the Darfur crisis.

The conflict in Darfur, dating back to February 2003, has left an estimated 50,000 people dead. The UN has threatened sanctions against Sudan if it does not take steps to disarm the Arab Janjaweed militias, responsible for much of the violence.

The crisis erupted when Sudan called on the militias to help subdue a revolt by the region’s non-Arab minorities.

“The international focus will not go away while this issue remains outstanding,” Blair said, describing his talks with Beshir and Taha as “frank and open and, I think, constructive”.

Blair warned that once Khartoum had committed to peace, “they have then got to follow through with practice.”

However, he played down the idea of sending British troops to the region, saying: “I am not sure there is any desire on the part of the African Union for outside forces to come in.”

Britain would, however, provide financial and logistical support to African Union peacekeepers, Blair said.