Livestock looting is another tragedy for Darfur families

By Emily Wax

MOYASHWA MARKET, Sudan, Oct 18, 2004 (The Washington Post) — One month ago, the body of Sulliman Bashir Nassir, a prominent man from an African tribe, was found slumped in his barn not far from this foul-smelling, overflowing livestock market in the Darfur region of western Sudan.

His killers were Janjaweed, his family said, members of a government-backed Arab militia that has terrorized and raided Darfur for months. The militiamen also took off with the family’s hard-earned assets: 800 cows, 450 goats, 20 donkeys and 6 horses, they said.

His killers were Janjaweed, his family said, members of a government-backed Arab militia that has terrorized and raided Darfur for months. The militiamen also took off with the family’s hard-earned assets: 800 cows, 450 goats, 20 donkeys and 6 horses, they said.

On a recent day, the local leader of Nassir’s tribe, Abdel Sharrifa

Gharida Abdel Rhani, drove a Land Rover through the soft sand to the

market, searching for the family’s animals. He looked for the brand — a

large circle with an X — that Nassir used to mark his herds. For 40

minutes, he scanned a field packed with more than 5,000 camels and 7,000

head of cattle.

“That’s our mark!” he said suddenly, pointing at a cluster of cattle.

“These could be them!”

Rhani started snapping photographs and writing notes in a thick folder.

But within minutes, an imposing man wielding an ivory-encrusted walking

stick marched over to the vehicle. He reached inside and grabbed the

wheel. “There is nothing here for you,” he boomed at Rhani. “Go. Go.”

The human suffering in Darfur is well documented: the burning of

villages that has driven 1.5 million Africans off their land and into

squalid refugee camps; rapes that have locked the population in fear;

and the unpunished killings of tens of thousands of people, most of them

men.

But another crime being committed in the region may prove just as

difficult to reconcile: the widespread looting of livestock. Stolen

animals worth millions of dollars have flooded markets like this one in

Nyala, the capital of South Darfur province, according to international

organizations and independent Sudanese investigators.

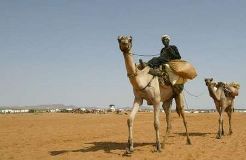

Cows, camels, goats and donkeys are a measurement of wealth and prestige

here. Each tribe has its own branding symbol, and families personalize

those marks for further identification. A camel, the Cadillac of

animals, runs $1,000. A cow, providing milk or meat, can cost $400. And

a donkey, reliable but less impressive, can set a family back about $150.

At refugee camps, where thousands of Africans have fled, threats of

reprisals are openly discussed. Without a government willing to

compensate them for their lost wealth, village elders said, revenge will

become the only way to reclaim it.

Some of the animals have been eaten at celebratory victory meals,

international aid workers investigating the issue said. But most have

wound up in large markets across Darfur, including a massive

slaughterhouse in El Obeid, the capital of the neighboring state of

North Kordofan, investigators said. Others have been sent to other

countries — to Chad, the Central African Republic and the Gulf states,

where demand and prices for good beef are high.

International aid organizations and a Sudanese group are investigating

the thefts and trying to trace the profits to determine whether they

have reached high levels of government. But many victims and traders

said the money has largely stayed in the hands of the Janjaweed.

“Janjaweed and Janjaweed leaders are getting rich off of this,” said

Adam Azzim Mohamed, a professor at the University of Khartoum, who is

tracking the profits from the sales. “There is an expression in Darfur

that says, ‘A man is powerless without his herds.’ What people outside

Sudan may not realize yet is how important the reprisals regarding these

animals may be. There will not peace until the government sorts out

this. . . . Otherwise it can be very dangerous.”

The conflict began 20 months ago when two African groups rebelled

against the Arab-dominated government, saying they had been politically

marginalized. International organizations say the government armed the

Janjaweed to put down the uprising. Facing international pressure, the

government conceded that it had armed some of the militiamen, but says

most are bandits outside its control.

Government officials said police in Darfur were investigating reports of

stolen herds and that victims would be compensated if their claims were

proved. But human rights advocates and villagers said they saw no

evidence of such an investigation. They countered that the Sudanese

government has failed to hold anyone accountable for crimes, creating an

atmosphere of impunity.

“The international community has got to hold the government responsible

for what has happened. They have trained, equipped and deployed the

Janjaweed forces,” said Peter Takirambudde, executive director of the

Africa division of Human Rights Watch. “If you talk about people ever

returning to their normal lives, clearly this would be a key

consideration. How can they go back without any of their principal

assets? Obviously, these guys don’t have Swiss bank accounts. I think

the international community must remain focused on pressuring the

government to get this done.”

When Charles Snyder, the State Department’s senior representative on

Sudan, visited Khartoum last month, he pressed the government to start a

reconciliation process for Darfur.

“There is a major tear in the social fabric of Darfur,” Snyder said.

“There has to be a system set up to hold individuals responsible.”

But so far, there are no signs that international pressure has stopped

the livestock thefts. At this meat market in Nyala, Nemen Maki Fage, an

Arab trader and butcher, attributed the abundance of animals to “spoils

of war.” He said he was unconcerned about tribal markings on the cattle.

Besides, he said, it was possible that the animals had not been stolen

but had simply been sold.

“The police don’t come here to investigate. And the prices of the cattle

are cheap, and no one stops us,” he said, proudly showing five head of

cattle he bought for $30 each. “This is Darfur right now.”

Days later, Rhani, the local tribal leader, read from stacks of police

reports: April 16 in Nyala — 12 people killed, 410 sheep taken. Two

months ago, in a nearby village, 400 horses stolen, and on and on. In

total, he said, he has reported 300 cases of stolen animals.

“But the government is quiet,” he said. “I report them and keep the

papers. If there is ever justice, I will use them.”

Later that afternoon, Rhani again drove to the market. In one corner,

Arab traders carrying cell phones prodded the cattle. Calls were made.

Money changed hands quickly.

In another corner, the pungent smell of freshly slaughtered meat rose in

waves as it was cooked over charcoal at dozens of tiny stands.

“They are roasting our wealth,” Rhani whispered.

The stench of detritus — a jumble of wrappings, stripped-clean bones

and plastic soda bottles — filled the dirt footpaths. Women carrying

tomatoes, basil, onions and plastic bags of salt hawked their goods.

A hulking leg of goat rested on a donkey cart, flies swarming happily

atop its pink skin. The meat was carried to the grill, where a long line

of customers waited.