Violence against Darfur’s women continues undeterred

By SOMINI SENGUPTA, The New York Times

KEBKABIYA, Sudan, Oct 26, 2004 — Even with the eyes of the world on this burned-out swath of western Sudan, threats of oil sanctions against the government and the trickle of African Union monitors into the countryside, one brutality has apparently continued undeterred: violence against Darfur’s women.

|

|

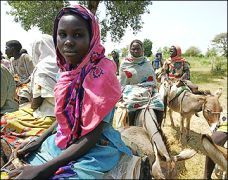

Sudanese youngsters move together while collecting firewood in fear of militia attacks in the remote village of Gokar. (AFP) |

Women were insulted, beaten and raped as their families were chased from their homes at the height of the war in this region. They continue to be insulted, beaten and raped as they try to eke out a living far from home in the miserable camps of the displaced across Darfur.

Judging from the accounts by victims themselves, as well as those of aid workers, human rights monitors and African Union military observers posted in Darfur, the victims are overwhelmingly women who belong to African communities here, and those who committed the acts are armed men who belong to Arab tribes.

Since early 2003, the war in Darfur has pitted the Arab-led government of Sudan against rebels who are led by members of African tribes.

Whether violence against women constitutes a war crime or whether it is part of a campaign of genocide remains unanswered. The United Nations secretary general, Kofi Annan, has appointed a panel of experts to determine whether the violence in Darfur meets the international legal definition of genocide. If previous United Nations inquiries are any guide, this one is not likely to offer swift answers.

Definitions aside, the more pressing question for people here, not to mention the credibility of the international community, is this: Can anything be done to stop it and then bring a measure of redress?

“Depending on the magnitude of it, it can constitute a crime against humanity,” said Louise Arbour, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights. Investigators in Darfur have not yet determined the magnitude. Eight of them are in the region, spread across an area the size of France.

For now the victims are left to the whim of local law enforcement, in which, it is apparent, there is little or no confidence. A recent inquiry by the Sudanese government turned up two cases of rape during the entire 18-month-long war in Darfur. Ms. Arbour, of Canada, rebuked the government, saying it was “in denial.” [On Oct. 23 the agriculture minister of Sudan, its chief negotiator in peace talks mediated by the African Union, described reports of widespread rape as “a lot of fabrication.”]

Violence against women in this conflict is not limited to rape. They are also verbally abused, threatened, robbed and beaten with whips, the reports say. These days they are most vulnerable when they trek out to do women’s work – fetch firewood.

Some of them bear gunshot wounds to the ankle, a sign that their attackers tried to keep them from fleeing. Others are marked as violated women. One woman in a refugee camp in eastern Chad lifted her veil not long ago to reveal a violent gash on her right cheek, and then she began weeping. She was sexually assaulted by five men, all in military garb, she said, during an attack on her hometown, Karnoi.

A report by Amnesty International, the London-based rights group, says some women have been raped in front of their relatives.

Fear and distrust in local law enforcement authorities runs so deep that the crimes are rarely reported to officials. When they are, victims and independent human rights observers say, little is done.

No international legal mechanism has been set up. Military observers from the African Union cease-fire commission take reports of abuse, but all they can do is report the cases to the United Nations human rights agency. “It’s a little bit ambiguous,” the United Nations official said.

The evidence on the ground has been overwhelming.

In January, during the height of the war, refugees fleeing into Chad said in interviews that attacks on their villages by the Sudanese military and the Arab militiamen whom they call janjaweed – or marauders on horseback – were frequently accompanied by sexual violence against women as they tried to flee.

In August, a refugee woman in a camp called Kounoungo in eastern Chad described vividly how two men on horses had hunted her down as she tried to run away from an attack on her village. One held a gun to her head while the other raped her. She was pregnant at the time. In the same camp, another woman held up the product of a violent assault: a baby boy with wavy hair, whom she called the son of a janjaweed.

Sexual violence has been a tried-and-true way for armed men to sow terror among civilians in wartime, from the Balkans to Colombia and Congo to the genocide in Rwanda. The latter offers a particularly trenchant lesson for Sudan: Ten years later only a handful of allegations of rape have been investigated and prosecuted, according to a recent report by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch.

Here, even after women have fled attacks on their hometowns and villages, they have not found refuge.

In early September, investigators with the United Nations refugee agency tracked down 13 women who said they had been raped in a period of 10 days just beyond a displaced people’s camp near Nyala, the state capital of southern Darfur.

In late September, a 13-year-old girl was taken by donkey cart to the African Union cease-fire commission’s office here with a chilling tale. Three men in uniform found her one afternoon as she was gathering firewood on the edge of town.

They called her Tora Bora, a reference to the place in Afghanistan that once was a stronghold of Al Qaeda. The pro-government militias here use the name to refer to the rebels or anyone they deem to be their sympathizers. The men took turns raping her. African Union monitors found blood caked on the dry earth.

Another woman, Hawa Ishak Mahmood, said she was on her way to seed someone else’s farm on the outskirts of Kebkabiya in the summer when four men on camel and horseback stopped her in her tracks. They accused her of looking like a member of the Zaghawa tribe, which dominates the chief Darfur rebel group.

Despite her denials, they beat her with the butt of their guns and wrestled her to the ground, she said. Then they took turns raping her.

She no longer ventures out to work on anyone else’s farm. She no longer collects firewood. Her children, ages 4 to 15, subsist on aid rations. “Always, when people go out, they get beaten, they get raped,” she said.

Reports like this no longer surprise Seth Appiah-Mensah, the African Union sector commander here. “It’s very common, almost on a daily basis,” he said. “When you report it the authorities say it’s not true. They always insist their soldiers are disciplined, they’re under Shariah, they won’t do this.” The Shariah is the Islamic legal code.

Who is committing the assaults remains unclear. Men in uniform here can be regular soldiers or members of pro-government militias. The lines are blurry.

Besides, the African Union’s mission is to monitor violations of the cease-fire between the government forces and the rebels. Rapes and other attacks against women are criminal offenses, and the organization has no law enforcement authority.

In early October, the police arrested a man who had gone to file a complaint with the African Union cease-fire commission about attacks on several women outside a displaced people’s camp near El Fasher, the state capital of northern Darfur. He was freed only through the intercession of a United Nations human rights investigator.