Darfur’s fearful displaced await peace, security

By Finbarr O’Reilly

ZAM ZAM, Sudan, Nov 2 (Reuters) – Under a sliver of shade from a thorn tree at Zam Zam camp in western Sudan, Aldoma Mohammed Adam scribbles Islamic verses onto tiny scraps of paper as a talisman to bring security and protection.

|

|

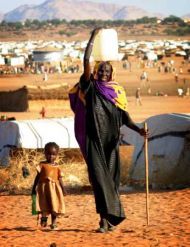

A displaced Sudanese woman carries water October 31, 2004 at the Abushouk camp near El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur province. |

He then folds the papers into small leather pouches and strings the pouches into amulets known as hijab, believed by many in western Sudan to guard against the kind of violent death that is all too common in the troubled Darfur region.

At the crowded Zam Zam camp just outside El Fasher, capital of North Darfur state, some 20,000 people live in makeshift shelters and tents after fleeing attacks that left their villages smouldering, looted husks in the desert.

And while many camp residents languish idle under the sparse shade of trees throughout the day, Adam keeps busy, his dry, cracked fingers making different hijabs that promise to ward off death from bullets, knives, artillery and bombs.

“I make them to demand and there is more and more demand every day,” says the 29-year-old, explaining that he fled his village of Zokhoa a year ago when it was attacked by Arab militiamen known as Janjaweed.

Like most people at the camp, Adam wants to go home but says that such a move would likely mean death, even if he wore every talisman his hands have ever made. “There is no security outside the camp. Nobody can leave here,” he says.

U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan toured Zam Zam camp during his visit to Sudan in June, when he pressed the government to improve security for Darfur’s population and allow greater access for aid groups working in the region.

FEAR OF ATTACK

Some obstacles have been lifted but aid groups say insecurity now hampers efforts to deliver food and supplies to 2 million needy people.

More than 1.5 million people have been made homeless in Darfur since two rebel groups, accusing the government of neglect, launched a revolt in early 2003 after years of skirmishes between African farmers and Arab nomads over land and scarce resources.

The United Nations says about 70,000 people have died from disease and malnutrition in the last seven months alone. The Sudanese government disputes that figure.

Another 200,000 refugees are encamped in the desolate eastern part of neighbouring Chad and the United Nations calls Darfur one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

Many residents at Zam Zam say they rarely venture far beyond the camp confines for fear of attack by armed men, though some people do seek menial work in nearby towns.

“Nothing has changed since Kofi Annan was here. It has gone from bad to worse, with more people arriving day by day,” says Ahmed Ali, 45, who lives at Zam Zam with his two wives and 19 children.

Policemen responsible for camp security sometimes abduct women or girls and “do bad things to them”, says Ali, using a coy euphemism for the rape that has accompanied the conflict in Africa’s largest country.

TRUCE MONITORS

Hundreds of African Union troops have arrived in El Fasher over the past week and a force of some 3,000 soldiers from Rwanda, Nigeria and elsewhere has the task of monitoring a shaky ceasefire and helping restore security to Darfur.

Peace talks in the Nigerian capital Abuja between Darfur rebel groups and the Sudanese government have made little progress, however, and few people at Zam Zam believe the foreign troops will make much difference in an area the size of France.

“I don’t think they can make peace here. They always come too late, after the problem has happened,” says 30-year-old Mohammed Juma, sucking his teeth and shaking his head.

Others, including 35-year-old Fatima Abdal Karim, are puzzled by the twist of fate the war has thrown their way.

Before she fled the village of Tabit with her 10 children early this year, Karim collected and buried her sister’s body parts, blown apart during a bombing raid by government planes.

“We are poor people. We don’t know about politics or why there is a war or when it will end. All we know is that we are here. We have enough food, but we are not happy to be sitting under this tree doing nothing all day, every day,” she says.