African troops begin with small steps to calm Darfur

By Finbarr O’Reilly

GELLAD, Sudan, Nov 20 (Reuters) – The rebels emerge from the desert haze like ghosts. First one, silhouetted atop a sand dune and holding a grenade launcher, then a dozen more, their shadowy figures appearing in unison.

|

|

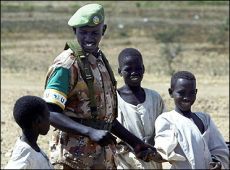

A Rwandan soldier operating under the Africa Union mandate plays with children outside the AU base in Kab Kabiya, north west of El-Fasher. |

Two vehicles carrying four African Union (AU) soldiers posted to western Sudan’s troubled Darfur region slide to a halt on the remote dirt road, surrounded.

The role of the recently launched AU mission, which so far has only about 700 troops on the ground, is to monitor a shaky cease-fire and try to restore order and security to Darfur, a violent, anarchic area the size of France.

It will be a huge task even once the full AU force of 3,320 personnel, including 2,341 troops and 815 civilian police from various African countries, completes its deployment by February.

In the meantime, those who have arrived do what they can.

A battered rebel truck with a heavy machine gun mounted on the back — but with no roof or windshield — pulls out from hiding and onto the road ahead of the AU team.

A similar vehicle draws up from behind, overloaded with armed men covered in dust and protective leather charms. Both vehicles were invisible moments earlier. Then the signal comes. “Follow us,” the lead rebel gestures with a wave.

“Did you see that ambush they laid on us? It was perfect. We never even knew they were there and we had no escape route,” said Col. Georges Niouky, a Senegalese officer with the AU mission.

Niouky’s assignment on this day is to negotiate with the rebels to release three commercial trucks that were hijacked in North Darfur state several days earlier.

NO RULE OF LAW

A wave of hijackings and abductions of government officials and Arab civilians in Darfur has been blamed on rebels from the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), which has fought the government and Arab militias since early 2003.

The SLA blames bandits, an easy thing to do since the rule of law has all but evaporated in Darfur, where fighting has driven more than 1.5 million people from their homes, creating what the U.N. calls the world’s worst humanitarian disaster.

A cease-fire agreement signed in April has been violated repeatedly by all sides in the conflict, which includes at least one other rebel group and Arab militias known as Janjaweed.

Rebels accuse the government of backing the Janjaweed, a charge Khartoum denies.

Sitting on the ground with the rebels under the shade of a thorn tree, Niouky gives his pitch to the gathering of armed men with guns slung over their shoulders.

“There are many stages of organizing a country, but for now, not all people are thinking the same. You must think about cooperation, even with the government,” he tells them, adding that improving the humanitarian situation requires security.

Many aid agencies have struggled to deliver assistance to volatile parts of Darfur and are hoping the AU presence can calm fighting and increase access to stricken areas.

“Maybe you have something to give us today for peace to come here in Sudan,” Niouky said in conclusion.

The keys to the first truck are handed over, but the second and third vehicles have been moved several hours away, deep into rebel territory, across an unforgiving terrain of roadless desert and looming mountain peaks.

LOST IN THE DESERT

Without water, the team sets off under a pitiless sun. When one of the speeding AU vehicles veers out of control, rolls over twice and comes to a halt upside down in the dirt, the team crawls out bruised and bloody, but undaunted.

They leave the crashed vehicle behind and crowd into the remaining Toyota pick-up for six more hours bouncing across the desert, past burned out, abandoned villages and sandy fields where dry yellow stalks of sorghum rustle in the hot breeze.

They occasionally get lost in the vastness or stuck in sand and dig themselves out with their bare hands.

When they finally reach the last two hijacked trucks, shadows are growing long. All the goods and fuel have been looted and the third truck will not start.

For all of their effort and persistence, the team recover only two of the three stolen trucks and none of the cargo.

Darfur’s complex war goes back to years of low intensity fighting between Arab nomads and mainly African farmers in the sprawling desert of Africa’s largest country.

The depth and scale of the crisis makes peace seem like a distant mirage and such relatively minuscule gains by the AU may only resemble grains of sand in the desert.

The AU mission however, hopes to assert itself through such incremental and mostly symbolic measures.

“At least these kinds of negotiations show that we are working with both sides in the conflict,” said Major-General Festus Okonkwo, the Nigerian chairman of the AU mission.

On returning after dark to El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state and the headquarters of the AU mission, a battered, thirsty and exhausted Niouky sighed with relief.

“We have earned our pay today,” he said. “And tomorrow we will do it again.”