Broken friendship shows the bitterness Sudanese conflict has caused

BY SUDARSAN RAGHAVAN, Knight Ridder Newspapers

MALEET, Sudan, Dec 10, 2004 (KRT) — Fadul Saim and Ismail Mumin have crossed the dust-choked road that separates their homes in this speck of a village thousands of times over the years, rekindling their friendship with every visit. But not now, in this time of war and suffering.

|

|

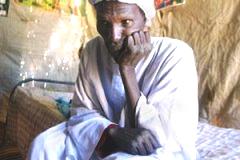

Ismail Mumin, the former friend of Fadul Saim at his house in Maleet, north Darfur. Ismail, a black African and Fadul, an Arab, were once good friends but are now divided along ethnic lines by the war in Darfur. (KRT) |

“If I cross, maybe they will beat me or kill me,” said Mumin, 45, a black African.

“If my tribe saw me speaking to Ismail, they may think I’m a spy,” said Saim, a 58-year-old Arab.

They’re casualties of the war that’s raked Sudan’s Darfur region, pitting largely black African rebels against the Arab-dominated government and militias. The conflict has killed 70,000 people and evicted 1.6 million from their homes.

In divided towns such as Maleet, as the violence blazes into its third year, fear and mistrust are scratched so deep into the collective psyche that many Arabs and black Africans predict they can never again live together as their forefathers had done for centuries.

“There is a deep grief in our society,” said Adam Muhammed Shamo, 78, the deputy sultan of Maleet. “Our lives will never be 100 percent the same.”

Thousands of Arabs and black Africans have fled towns like Maleet as the conflict spread, bolting up their shops and homes. Those who remained have sought sanctuary in their own tribes, and close friends who transcended ethnic identities are now distant enemies.

Less than a football field of caramel sand separates Saim’s green door from Mumin’s blue one. But the gulf between them is as wide as the desert that surrounds Maleet.

Saim, who belongs to the Arab Zayadia tribe, hasn’t invited Mumin, a member of the black African Barti tribe, to his house since May 2003, when the rebels first attacked Maleet. Saim knows “he won’t come,” and he refuses to visit Mumin’s house because he knows “I will not be welcome.”

Indeed, Mumin at first denied even knowing Saim: “I have no relationship with him. He is not my friend.”

A son corrects him, once he leaves the room. “They know each other from the past,” said Abdou Ismail Mumin, 20. “They used to visit each other. They’ve attended ceremonies together in our neighborhood and theirs across the road.”

For decades, Maleet was a vibrant town in which the Barti and Zayadia mixed seamlessly. They lived in adjacent neighborhoods. They hawked goods side by side in stalls. They loaned each other money. During the Muslim festival of Id, the sultan of Maleet, a Barti, would visit the Zayadia to pay his respects.

There were, of course, historical rivalries over land and water between Arab herders and black African farmers. And the Barti often resented how the Arab-led government in Khartoum favored the Zayadia. But no road ever seemed too hard to cross.

The Barti even trusted the Zayadia with their most precious commodity: livestock. For a small fee, Arab nomads would graze the Barti cattle and sheep, taking good care of them. There were no contracts. Their word was enough.

“Even if they asked us to give a woman in marriage from our tribe, we wouldn’t say no,” said Shamo, who’s a Barti. “We didn’t have any hate in our hearts at that time.”

The friendship of Saim and Mumin blossomed in this climate. Saim first met Mumin’s older brother Muhammed in his early 20s. They traveled with their cattle together to Libya. Mumin sometimes would come along, and a bond grew between Saim and him.

“We were very close at that time,” Saim said. “We would never talk about being from different tribes.”

The three would eat and spend the night at each other’s houses. They invited each other to baby namings, circumcisions, marriages and other ceremonies. Then one day, Saim’s niece married Muhammed, sealing their friendship. When the couple had children, Saim treated them as if they were his own.

Five years ago, Muhammed died. At the funeral, Saim served food, a duty usually performed by close family members.

“After Muhammed’s death, Ismail became like Muhammed to me,” Saim said. “He visited my house. I visited his. We grazed our cattle together. We once spent a whole summer together.”

But the conflict has taken its toll. Nine months ago, Saim noticed a funeral ceremony unfolding at Mumin’s house. So he went to pay his respects. But as he got to the door, ugly stares pierced his confidence. He walked back across the road.

Three months ago, a gang of men – the Barti say they were Arab militiamen – raided Mumin’s house and grabbed his 30-year-old nephew, Ali, accusing him of being a rebel. They beat him, then dumped him 40 miles away.

Mumin blames the Zayadia.

“I feel betrayed, because we used to share everything,” he said. “Now they are shooting at us and taking our belongings.”

Today, Maleet is crisscrossed with roads that people won’t cross. The Barti and the Zayadia pray in separate mosques, and take their livestock to separate grazing areas. About the only place where they mix is at the Mowasha, an animal trading market that takes place every Saturday.

A few days ago, Saim ran into Mumin in the center of town. They quickly exchanged greetings and moved on.

“If we had met in the past, we would have sat together and chatted over a cup of tea for maybe a half hour or more,” Saim said.

Mumin refused to discuss Saim. He said Saim’s niece married his brother, but that she was “not even his direct niece.”

Last weekend, seven Zayadia children flew kites in front of Saim’s green door. They included Muhammed Fadul Saim, 12, his straight-haired, lanky son. They obeyed their parents’ orders to stay on their side of the road.

“I don’t have any friends there,” Muhammed said, looking across the road. “They are afraid of me. They claim they will be beaten by me.”

“They are not coming here. I don’t go over there,” he added, shyly fiddling with his plastic kite. “We are afraid of each other.”

A few minutes later, a group of Barti children came out of Mumin’s blue door. Among them were the son and daughter of his dead brother, Muhammed.

“I’m not allowed to cross the road,” said Marwa Mumin, 13, a slender girl with large maple-brown eyes and black curls. “I don’t know why.”

Fifteen minutes later, Saim strolled down the middle of the road to have his picture taken. He didn’t say a word to Muhammed’s children, borne by his niece.

Suddenly, both groups of children converged on the road. For a brief moment, they mingled, giggling and laughing.

Then, just as quickly, they crossed back.