Child’s-eye view of a hellish place

By Kristen A. Graham, The Philadelphia Inquirer

Dec 16, 2004 — Jerry Ehrlich gave the children of Darfur shots and medicine. He cradled the dying ones when there was nothing more he could do for them.

|

|

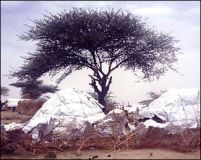

At the Kalma camp in western Sudan, tents housing families of three or four are clustered on the desert floor. Cherry Hill pediatrician Jerry Ehrlich spent two months treating refugess there in the summer. |

The children of Darfur offered the Cherry Hill pediatrician – who crawled from mat to mat to care for them half a world away – drawings.

Vivid blues and oranges against ordinary tan construction paper. Crayon pictures that gave Ehrlich, a 13-year volunteer with the international medical-aid group Doctors Without Borders, a profound glimpse into life in western Sudan, a region the United Nations has called the site of “the worst humanitarian crisis in the world.”

The doctor was so moved that when he returned home, he helped coordinate an art exhibit and panel discussion to educate people about the genocide in Darfur.

The exhibit and discussion will be presented tomorrow in the Art Sanctuary of the Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia.

Clearly, the work is enormously meaningful to Ehrlich, 69, who has had a pediatric practice in Cherry Hill since 1966.

“The American presence working in the middle of this was important,” he said. “No one should live that way. No one should live in those conditions. Every day, they had to line up for something – a mat, a plastic sheet, food.”

An Arab militia called the Janjaweed, which is tied to the Sudanese government, has killed tens of thousands of black Africans in Darfur, including entire villages, and has displaced almost two million people. Some have called it genocide.

In the summer, Ehrlich, who has spent much of his Doctors Without Borders time in Sri Lanka, got a call from the group to work in Kalma, a camp for displaced people in Darfur. Although it was forbidden, he smuggled in a camera to record life there.

Pointing to a picture of three small tents grouped together, he said: “This is all straw, covered with plastic sheeting. Families of three or four live like this, 90,000 in all.”

In the two months he worked in Darfur, Ehrlich treated measles, respiratory-tract infections, diarrhea, pneumonia and, most commonly, malnutrition.

“Look at this child,” he said, pointing to another photo. “He’s 2 years old, and he looks like he’s 102. When you’re this malnourished, you’re severely immuno-compromised. So many of them died.”

But they were children, after all, and while they waited for the doctor to treat them, he gave them crayons and paper.

“I just said, ‘Draw what your life in Darfur is,’ ” Ehrlich said.

By the time they arrived at the medical tent, some were too far gone to draw, wasted by illnesses few American children ever know.

But others took to the task gladly.

Some made faint scenes, as if the children were weak or bored or had too long to wait. Some pressed hard and used bright colors. Most depicted guns, soldiers shooting, and planes dropping scary things from the sky as easily as they colored trees green and flowers purple.

Flipping through them, Ehrlich showed flashes of anger.

“They would blow up the villages – these Arab militias would come in and kill them, rape them. This mother could have been my patient,” he said, pointing to a photo he took of a dead-eyed woman in a blue scarf and loose white wrap holding a toddler with a distended belly and vacant eyes.

“You don’t leave that behind,” Ehrlich said.

Chris Thompson, education coordinator at the Church of the Advocate, said the decision to accept the pictures was easy.

“The whole story is just – I don’t want to use a pretty word – but it takes your breath away,” he said. “It was important for us to display.”

Some drawings are blown up to mural size on 4-by-8-foot panels so passersby can understand the impact of airplanes and soldiers as seen by small, frightened children.

“We’ve got kids on our streets, and we’re horrified by what’s happening to them, and this is magnified by 10,” Thompson said. “The only thing I can hope is that it has some kind of impact.”

Africa feels so far away, Thompson said, and this is a way to make it real.

Artist and activist Lou Ann Merkle, whose work has centered on victims of war, got involved with the cause after speaking with Ehrlich and seeing the drawings.

“I took a look at them and immediately understood the power of these drawings and photographs,” she said. “They seemed like the perfect vehicle for drawing attention to this issue.”

Now that the works are in place in the sanctuary, Merkle said, everyone realizes that the exhibit has to be more than one day. Church officials are talking about keeping the art longer, and she hopes to take the show on a local or national tour.

“This is about wanting to amplify the children’s voices,” Merkle said.

Ehrlich knows that better than anyone. He looked at a photo the translator had taken of the doctor with his arm around a happy-looking boy, wearing an enormous white shirt, who had managed to recover from pneumonia. The boy held his picture up and smiled widely.

“Maybe,” Ehrlich said, “he’ll grow up to be mayor of that town.”