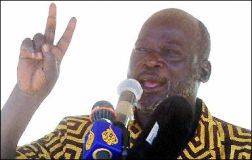

Garang: rebel leader once derided as Soviet stooge

NAIROBI, Dec 30 (AFP) — The expected peace deal ending more than two decades of civil war in south Sudan by Friday will be a triumph for rebel leader John Garang, who rode the shifting allegiances of the Cold War and its aftermath to win his people a vote on independence.

With the full blessing of Washington, the balding US-educated economist turned guerrilla it once derided as a Soviet stooge, finally won respectablity as the leader of an internationally endorsed autonomous administration.

With the full blessing of Washington, the balding US-educated economist turned guerrilla it once derided as a Soviet stooge, finally won respectablity as the leader of an internationally endorsed autonomous administration.

But as he swaps his military fatigues for civilian clothes, he faces a daunting task rebuilding one of Africa’s least developed regions after the continent’s longest-running conflict.

Born in the remote Bor district in 1945, Garang was one of the few in south Sudan under British colonial rule to enjoy education beyond primary level.

After completing his secondary education in Tanzania, he went on to study economics at Grinnell College, Iowa.

In 1970, he walked away from the offer of a graduate fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley, to take up arms against the Khartoum regime.

The so-called Anyanya uprising ended with a 1972 Addis Ababa peace agreement under which Garang joined the Sudanese military, eventually rising to the rank of colonel and receiving training at the US army infantry school in Fort Benning, Georgia.

He returned to the bush in 1983 after then president Gaafar Mohammed Nimeiri imposed Islamic law in defiance of the 1972 truce.

Ironically, Garang had been sent by the government to suppress a mutiny by southern troops in his home district of Bor.

The 105 Battalion of the Sudanese army, which he had commanded in the 1970s, became the nucleus of the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army.

Washington’s Cold War alliance with the Khartoum government prompted Garang to throw in his lot with the pro-Soviet government in neighbouring Ethiopia.

He was later to dismiss the alliance as a “marriage of convenience” but it earned him abiding accusations of authoritarianism from the west.

The overthrow of the Soviet-backed regime in Addis Ababa in 1991 prompted a disastrous split in rebel ranks which brought Garang to his lowest ebb.

The SPLA divided on ethnic lines with Garang maintaining the support of his Dinka tribe, while the rival Nuer sided with breakaway leader Riek Machar.

The subsequent internecine fighting between the two sides appalled even sympathisers of the southern cause.

A 1994 report by New York-based Human Rights Watch accused all sides of gross violations of the rules of war, while aid agencies charged rebel and army commanders alike of diverting desperately needed relief supplies.

As the Islamist-backed regime brought to power by a 1989 coup sent waves of volunteer militiamen to the south, Garang’s troops were forced back from the large swathes of territory they had occupied to a narrow border strip.

However the coup was ultimately to prove a blessing in disguise as the new government’s policies pushed northern opposition groups into alliance with the SPLA and discredited Khartoum in US eyes.

In the early 1990s, the regime gave refuge to Osama bin Laden, a decision that prompted a US missile strike on the Sudanese capital in 1998.

The election in 2000 of US President George W. Bush, whose Republican Party included many Evangelical sympathisers with the Christian cause in south Sudan, provided a further boost.

Through the long and often painstaking negotiations that followed a framework agreement in July 2002, it was Washington that maintained the momentum propelling the two sides forward.

His acceptance in Kenyan peace talks that any deal would be restricted to the south and three disputed adjacent areas helped spur a new uprising by rebels in Darfur early last year, sparking what the United Nations describes as the world’s worst current humanitarian crisis.

Now that the war is finally over, Garang makes no secret of how much remains to be done to win the peace.

“We’re going to have to fight, but this time without weapons,” he told AFP earlier this year at his headquarters in the bombed out rebel-held town of Rumbek.

“We haven’t had tarmac roads since creation. We are literally starting from scratch,” said Garang, who is still obliged to travel around his 850,000-square-kilometre (333,000-square-mile) domain by plane.