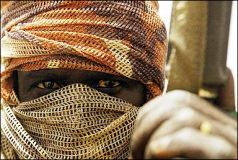

How credible is Darfur’s third rebel movement?

NDJAMENA, Jan 13, 2005 (IRIN) — A third rebel movement has appeared in

Sudan’s troubled Darfur region, but nobody seems to be taking it very

seriously, apart from the authorities in Khartoum and the government of

neighbouring Chad.

Recent weeks have seen a flurry of negotiations between this newcomer, the

Recent weeks have seen a flurry of negotiations between this newcomer, the

National Movement for Reform and Development (NMRD) and Sudanese

government envoys in the Chadian capital N’Djamena and the border town of

Tine.

In contrast to the slow-moving peace negotiations with the two main rebel

groups in Darfur, the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and

Equality Movement (JEM) in the Nigerian capital Abuja, Khartoum’s talks

with the NMRD in Chad appear to have made rapid progress.

The two sides agreed a ceasefire on 17 December and on 3 January they

struck a deal to promote the return of refugees from Chad to areas which

the NMRD claims to control.

However, UN refugee officials in eastern Chad told IRIN they had seen no

evidence of fugitives from Darfur trekking back across the border, despite

images purporting to show such returns broadcast by Sudanese state

television and affirmations by Chadian officials that some Sudanese

refugees have gone home.

“In the camps there have been no massive refugee returns, as reported by

the press, and the refugees are sceptical of any return given the security

situation prevailing in the Sudan,” Claire Bourgeois, the head of the UN

refugee agency UNHCR in the eastern town of Abeche, told IRIN.

Bourgeois said that on the contrary, new arrivals were continuing to

trickle into the semi-desert of eastern Chad to join the 200,000 who have

sought sanctuary there already.

Many of the new arrivals had fled to the mountains following fighting

inside Darfur, but were now crossing the border to camps near Iriba and

Bahai because they had run out of food, she added.

Both these Chadian towns are near Tine, the border settlement where the

NMRD signed a deal that was supposed to lead to refugees returning

voluntarily to Darfur.

Another UNHCR official in eastern Chad, Lino Bordin, said some refugees

had been making brief trips across the border to benefit from money and

assistance packages offered by the Sudanese authorities to returning

refugees. But once they had grabbed their cash and food parcels they

hurried back into Chad, he added

“All refugees questioned by the UN say they do not want to go back,”

Bordin told IRIN. He stressed that UNHCR had no plans to repatriate any of

them in the short term.

The NMRD claims to be a breakaway movement from JEM.

NMRD leader Nourene Manawi Bartcham, told an IRIN correspondent in

N’Djamena at the end of December that his group broke away from JEM in

April last year because it disagreed with the influence of Hassan Al

Tourabi, an Islamic fundamentalist politician, over the rebel movement.

Tourabi helped Sudan’s current military head of state, Omar Hassan Al

Bashir, seize power in a 1989 coup and subsequently became an influential

figure in his administration. However, the two men fell out 10 years later

and Tourabi went into opposition.

Bartcham claimed that the NMRD had an important presence on the ground

throughout Darfur, an arid territory the size of France. He said the

movement controlled territory near the main border crossing at El Geneina.

“We have men and weapons and the capacity to be a real nuisance,” he told

IRIN.

But Bartcham added: “We want peace and that is why we have accepted

President Deby’s invitation to come to N’djamena to sign the ceasefire

agreement.”

Ahmad Allami, an adviser of Chadian President Idriss Deby who has acted as

a mediator in several rounds of peace talks with all three rebel movements

in Darfur, said the NMRD were a force to be taken seriously.

He estimated that the movement had about 1,000 fighters on the ground.

“Contrary to what has been said, the NMRD do represent something in Darfur

as they managed to prompt a number of Sudanese refugees to return to

Sudan,” Allami told IRIN.

A western diplomat based in N’Djamena also cautioned that the breakaway

rebel movement should not be dismissed too lightly. “Our indications are

that the NMRD should not be under-estimated since a sizeable part of JEM’s

military capacity appears to be under their control,” he told IRIN.

But as far as JEM itself is concerned, the NMRD is just a stooge of the

authorities in Khartoum.

“This group belongs to the Sudanese government.It is very strange that the

government negotiates with itself,” said Mohamed Ahmed Tugod, a JEM

negotiator at the currently suspended peace talks in Abuja.

The conflict in Darfur erupted in February 2003 when rebels in the

territory, which was traditionally a key recruiting ground for the army,

took up arms against the government.

Since then, the United Nations estimates that tens of thousands of people

have been killed in fighting or have died from hunger and disease.

Nearly a third of the territory’s six million inhabitants have been forced

to leave their homes, mainly as a result of raids on black African

villages by Arab nomads grouped in the pro-government Janjawid militia

movement.

The United Nations estimates that 1.65 million are internally displaced. A

further 200,000 have fled to Chad.

Briefing the UN Security Council on Tuesday this week, Jan Pronk, the

United Nations special envoy to Sudan, made no reference to the NMRD as a

player in the Darfur conflict.

But he warned that security situation was still bad, the humanitarian

situation was poor and the region was still in a political stalemate.

Pronk accused the rival factions in Darfur of rearming and pointed to a

recent increase in banditry and looting. He also drew attention to the

recent spread of armed conflict to the neighbouring province of Khordofan.

And the UN envoy was dismissive of all agreements signed so far to bring

an end to the fighting.

“Talks between the parties on Darfur have not yielded concrete results or

much narrowing of the gap on the issues concerned,” Pronk said. “Despite

regular statements to the contrary, the parties have yet to commit in

practice to the implementation of the humanitarian ceasefire (agreed in

April 2004).”

However, hinting at the need to include other groups besides the SLA and

JEM in the political dialogue, Pronk said: “It would be useful to start

thinking of including tribal leaders in finding political solutions even

before reconciliation has taken place. That may include tribes that so far

were beyond control by the government or by the rebel movements and were

fighting to protect their own interests.”

Could that perhaps point to a role for the NMRD in the overall negotiating

process?

Allami, the Chadian mediator, also advised that the peacebrokers in Darfur

should cast their net wider.

“We should involve all the political and military forces in a definitive

and global settlement of the crisis in Darfur,” he told IRIN.