Darfur genocide investigation may land in IC Court that US opposes

By JESS BRAVIN and SCOT J. PALTROW, The Wall Street Journal

UNITED NATIONS, Jan 17, 2005 — In its effort to stop the mayhem in Sudan’s Darfur region, the Bush administration soon may be forced to choose between prosecuting the perpetrators and continuing to shun the International Criminal Court.

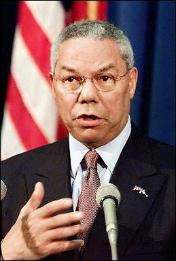

The dilemma arose in September, when Secretary of State Colin Powell labeled the massacres in Darfur “genocide,” triggering legal obligations to address the crime under the Genocide Convention. To buttress its finding, the U.S. supported establishing a United Nations commission to investigate the Darfur situation, decide whether it amounted to genocide and advise the Security Council on how to punish those responsible.

The dilemma arose in September, when Secretary of State Colin Powell labeled the massacres in Darfur “genocide,” triggering legal obligations to address the crime under the Genocide Convention. To buttress its finding, the U.S. supported establishing a United Nations commission to investigate the Darfur situation, decide whether it amounted to genocide and advise the Security Council on how to punish those responsible.

The commission’s report is due by month’s end and is expected to recommend that the Security Council refer the case to the ICC — a tribunal the Bush administration considers a threat to American interests. The depth of U.S. opposition to the court, which sits in The Hague, was underscored last month, when Congress approved legislation to cut off aid to countries that don’t sign pledges promising not to cooperate with the ICC should it investigate an American.

The U.S. could veto a Security Council referral to the court. But that would invite charges of hypocrisy and would worsen considerable international ire over Washington’s hostility to the court.

Despite reservations about the court, Rep. Frank Wolf, a Virginia Republican who is co-chairman of the Congressional Human Rights Caucus, says it may present the best way to seek justice for Darfur. If the commission recommends sanctions, a weapons embargo and a travel ban on suspected perpetrators, “and with it was a referral to the International Criminal Court, frankly I would take the deal and go,” Mr. Wolf says. “It would be better than doing nothing.”

But the Bush administration opposes the idea, not because it could bring Americans before the court but rather for the legitimacy a referral could impart to the fledgling tribunal. “We are studying options and the ICC is not one of them,” says a U.S. official who monitors the court.

The Bush administration sees the ICC as a threat because its independent prosecutor and judges are able, in theory at least, to prosecute U.S. agents and military personnel for actions in ICC member countries. But the ICC has strong supporters among U.S. allies. Britain and Australia argue that safeguards were built into the 1998 treaty establishing the court to prevent politically motivated prosecutions.

Supporters say the ICC is a court of last resort to address crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide in places where judicial systems have collapsed. “To put it bluntly, the International Criminal Court was created precisely for situations like Darfur,” says Richard Dicker, director of the international-justice program at Human Rights Watch in New York.

In Darfur, where the U.N. estimates 1.85 million African villagers have been driven from their homes, the U.S. blames Sudanese government forces and Janjaweed Arab militias for the violence. The outlook is grim: Peace talks were suspended last month and the British branch of the charity Save the Children said it was pulling out its 350-member staff after four workers were killed. The Sudanese Mission to the U.N. didn’t return calls seeking comment.

Established in 2002, the ICC has investigations under way in Congo and Uganda, at the invitation of their governments, and is weighing a request from the Central African Republic to begin one there. But it hasn’t yet brought a case to trial or received a referral from the Security Council.

While the court can act on its own to prosecute individuals in the 97 countries that have ratified the treaty, it can’t act without a Security Council referral in cases against nonmember countries, such as Sudan and the U.S.

Michael P. Scharf, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, who is helping to train the Iraqi judges who will try Saddam Hussein, says that blocking the Darfur referral “would do incredible damage to the United States’ image abroad.” Such a move, he says, would “feed into the idea that the U.S. has become a law-breaking country instead of a law-supporting country.”

The U.S., however, might not be alone in opposing a referral. China and Russia, which also never ratified the Rome Statute establishing the ICC and also hold vetoes at the Security Council, are reluctant to hurt their relations with Sudan , where they have oil interests.

Washington has a choice of paths, none of which appeal to the Bush administration. It could abstain on the referral, allowing the case to move forward. But it might bargain for concessions from major European Union countries, which have refused to sign pledges that they won’t support the court if it goes after Americans.

The U.S. also could push to expand the jurisdiction of the U.N. tribunal for Rwanda to include crimes in Sudan — even though the U.S. has been calling for the Rwanda and Yugoslavia tribunals to wind down their work.

A third option would be an ad hoc tribunal for Sudan — one that the U.S. likely would have to fund because most industrialized countries already pay for the ICC and aren’t likely to shell out more for a new court. Richard J. Goldstone, a former chief prosecutor of U.N. tribunals in The Hague, says a new court would be inefficient and unnecessary. “I can’t see the United States wanting to set up a new ad hoc tribunal when the ICC is up and running,” he says.

The five-member U.N. commission examining the Darfur situation is in Geneva preparing its report, having visited the region in November. The group, headed by Italian jurist Antonio Cassese, a former president of the U.N. war-crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, has declined to comment. Jose Diaz, a spokesman for the U.N. Human Rights Commission in Geneva, said the panel wants to avoid stirring up any effort by diplomats to influence their conclusions.

U.N. officials such as Juan Mendez, U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s special adviser for the prevention of genocide, say the commission is likely to recommend referral of Darfur to the court. “I cannot imagine that they will not say that crimes against humanity and war crimes have happened, and on a very important scale,” Mr. Mendez says, adding “I don’t see too many ways in which this can be done practically other than a referral by the Security Council to the ICC.”

Prof. Jack Goldsmith of Harvard Law School, a former assistant attorney general in the Bush administration and a longtime ICC critic, says that abstaining on a Security Council referral “would be consistent” with Washington’s formal position: It is “neutral on the ICC’s development as long as U.S. personnel are not haled before it.”