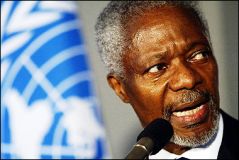

Annan warns Sudan to stop Darfur killing or face punishment

UNITED NATIONS, Feb 3, 2005 (AP) — U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan demanded speedy prosecution of Sudanese officials and militiamen guilty of crimes against humanity in Darfur, as members of the Security Council came under renewed pressure to tackle the issue at last.

The push to end what has been labeled the world’s worst humanitarian crisis gained impetus after a U.N. panel released a report Monday that said government-backed militias were still conducting rape, mass killing and wanton destruction in Darfur.

The push to end what has been labeled the world’s worst humanitarian crisis gained impetus after a U.N. panel released a report Monday that said government-backed militias were still conducting rape, mass killing and wanton destruction in Darfur.

The Security Council, and by extension the United Nations, have been dogged by allegations that they are standing by and doing little as thousands of people die in Darfur.

Annan said Wednesday that on a recent trip to Abuja, Nigeria, he warned Sudanese leaders to rein in the so-called Janjaweed militia or face punishment — possibly including sanctions. He said that leading suspects in the killings, whose names were provided to him in a secret annex to the report, must be tried urgently.

“I think the commission was right in saying that it is important that urgent action be taken, and the perpetrators be brought to justice,” Annan said. “They have to be prosecuted.”

The Security Council, ratcheting up pressure to resolve the Darfur crisis, has asked two key Sudanese players to appear before the council next week — Vice President Ali Osman Mohammed Taha, and John Garang, head of the main southern Sudanese rebel group that just signed a peace deal with the government.

After closed-door talks on Wednesday, Benin’s U.N. Ambassador Joel Adechi, who holds the revolving Security Council presidency for February, said members “stand united in their agreement and their determination to make sure that impunity is not allowed and is addressed in some internationally recognized way.”

The U.N. envoy for Sudan, Jan Pronk, said Wednesday in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, that there were 51 Sudanese on the list, including “very high-level officials,” rebels and Janjaweed militiamen.

He said that the government policy toward the militia had not changed and attacks on several towns had continued. One place he visited, Labado, had been wiped out, he said.

“I was horrified by what I saw in Labado,” he said, referring to a South Darfur town of 27,000 people where rebels fought with pro-government forces in December. “All huts have been demolished or burned down. All water wells have been destroyed. There is nothing left in Labado.”

Violence in Darfur has killed tens of thousands of people and forced nearly 2 million people to flee their homes. While there has been international focus, so far the Security Council has been more focused on a peace deal to end Sudan’s civil war between the north and the south. A deal was reached Jan. 9.

Darfur has also become a hot political issue in Washington. The Bush administration and Congress have labeled the crisis genocide, and have pointed to the U.N. Security Council’s delays as evidence of U.N. ineffectiveness.

While the commission report concluded there was not genocide in Darfur, it spelled out crimes including the disproportionate use of force, mass burnings of villages and other acts it said were just as heinous. It didn’t rule out that a court may later find some people were guilty of “genocidal intent” in Darfur.

Some Security Council members want to link the Darfur crisis with the recent ending of the civil war — possibly by withholding economic and humanitarian aid tied to that deal unless violence in Darfur is stopped.

There could also be an arms embargo or other actions.

Those issues will be discussed when the council meets next week, hopefully with Taha and Garang.

Garang has said the north-south peace deal meant southerners would have to help negotiate settlements to other conflicts in Darfur and east Sudan.

“You cannot specifically talk about a peace mission in the context of the north-south negotiations without having in mind what is happening in Darfur,” said Benin’s Adechi.

There is also the issue of accountability for those guilty of abuses in Darfur. Several European nations want the case referred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands, as the commission report recommends.

But the United States, an opponent of the court, wants a separate tribunal based in Arusha, Tanzania, to prosecute alleged perpetrators.

Annan, a supporter of the court, said the venue of the trials wasn’t as important as action.

Britain’s U.N. ambassador, Emyr Jones Parry, said the council needs to do “two things crucially: one to stop any more atrocities in Sudan and secondly to address those things that have happened.”

“My primary interest is in addressing them in a way (of) getting an outcome under a council that is united,” he said.

Adechi said he hoped the Security Council could take action within 15 days.