Darfur refugees live within sight of their homes

By Opheera McDoom

TINE, Chad, Feb 10 (Reuters) – Sudanese refugee Bakhiet Sandal Rajab lives 50 metres from his home — but he dare not go back to live there for fear of being caught in the middle of a two-year-old rebellion in Sudan’s Darfur region bordering Chad.

|

|

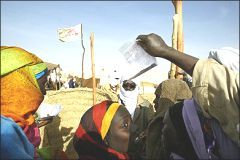

Refugees of the Sudan Darfur area wait outside the MSF field hospital in Tine seen here in January 2004. (AFP). |

“If we go back the opposition (rebels) may kill us thinking we are with the government, and the government may accuse us of being with the rebels and kill us,” he said.

Rajab and thousands of other refugees have lived on the Chadian side of Tine town for 13 months since they fled battles between rebels and government forces in Sudanese Tine. The towns are separated by a dry river bed.

A makeshift refugee camp extends Chadian Tine’s suburbs by a few kilometres on all sides. Buses and trucks fill the marketplace, ready to transfer hundreds of Sudanese back to the camps set up by aid agencies away from the border and which house more than 200,000 refugees.

Mohamed Mansour Dousa said rebels had told the refugees not to go back to the Sudanese side. He is the son of the leader of the main Zaghawa tribe in Tine and wears Sudanese traditional white turban and galabiyya.

“And we don’t want to go back until there is a final peace deal between the rebels and the government,” he said. “Otherwise war could break out at any time — there’s no guarantees.”

Many of the lesser-educated women repeated stories they had clearly heard over and over again. “(President) Omar al-Bashir will kill us if we go back. The Janjaweed are his family,” Tanbus Adam Haggar said, flashing a toothless grin. “People say the Janjaweed are still there, attacking,” she said.

Refugees say Arab militias they call Janjaweed carried out a campaign of rape, killing, looting and burning in non-Arab villages in Darfur. The international community accuses Khartoum of arming and supporting the Janjaweed, a charge the government denies.

The colourfully dressed women described pictures of sprawling Sudanese Tine completely flattened by government bombardment, and did not believe it was mostly still standing, if completely empty.

Adam Shatta, a Zaghawa, said Janjaweed shot and killed three of his children. He managed to save two by heaving one on each shoulder and running to safety across the border to Chad in February 2004.

“I want to go back and will, but only when the government gets rid of the Janjaweed,” he said. “My farm is still waiting for me.” He said non-Arab tribes could go back but the Zaghawa would never go back until there was a final peace deal.

“We, the Zaghawa, are the base for the revolution,” he said. “That’s why the government wants to kill us.”

AU NOT TRUSTED

Najmeddin Ibrahim Eissa said the African Union, mandated to monitor a shaky ceasfire between the warring parties in Darfur, was not well liked among the general population.

“They are seen to be too sympathetic with the government because they have such close relations and cooperate so much together,” he said. “I don’t have anything against them personally but they do need a wider peace-keeping mandate.”

Sudanese Tine was a bustling town of tens of thousands but now about 150 people live there with about 3,000 government soldiers, who fill the market place.

The AU camp of about 90 soldiers lies a few hundred metres outside the town and is the only life to be heard at night, apart from sporadic eery whispers blown over on the wind from acoss the border.

“The people will only go back when the army soldiers leave the town and the African Union soldiers move into Tine,” said Hussein Bishara Dousa.