Coping with disease and drought in Upper Nile

MALAKAL, March 7, 2005 (IRIN) — The small child lay motionless on a hospital bed in Malakal, a garrison town in central Sudan. Severely malnourished, the child had a high fever and a number of other unidentified medical complications.

|

|

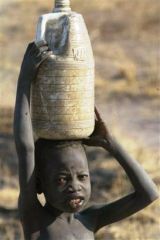

A Sudanese boy carries water in a plastic container Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2005 in Rumbek in southern Sudan. |

Medical staff said the child was suffering from Kala Azar – a severe parasitic infection transmitted by the female sand fly, which mainly lives in Acacia and Balamites woodland. Left untreated, it is fatal in 95 percent of the cases.

“Most Kala Azar patients arrive in the hospital unable to walk and have

other co-infections, such as TB or malaria, because the disease destroys

the body’s immune system,” George Mbaluto, a nurse working for the medical

charity MSF-Holland which runs the hospital, told IRIN.

“They are usually severely malnourished and are often carried here by

relatives,” he added.

The temperature in the intensive care unit was 48 degrees Celsius, as the

heat of the dry season simmered over Malakal. It was so hot that before

taking the child’s temperature, the nurse had to dip her thermometer in a

bowl of cold water to cool it down.

According to the medical personnel at the hospital, the Kala Azar season

in Upper Nile coincides with the dry season. It lasts from

September-October until January-February. During this season there is also

an increase in dust-induced pneumonia, as well as bloody diarrhoea.

“The water-level of the River Nile is very low around this time of the

year and people drink directly from the river, while they also use it to

bathe and wash their clothes,” Samuel Nyitwel, the supervisor of the

hospital’s in-patient department, told IRIN.

Widespread in Few Countries

According to the World Health Organization, there are 500,000 new cases of

Kala Azar per year in 88 countries around the world. However, 90 percent

of all the cases occur in only five countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, China,

Nepal and Sudan.

In Sudan, it is found in a belt that runs from Unity State, through Upper

Nile, Blue Nile, Sennar, and Gedaref, up to Kassala in eastern Sudan. It

is also found in some parts of Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and Eritrea.

Mbaluto said new Kala Azar patients usually had to spend 30-45 days in the

intensive care unit to stabilise the disease and treat complications. On

average, Kala Azar patients remain in the hospital for one to three months

before they are discharged.

Most patients who receive treatment recover, but some die. Recently, a

small girl died of co-infections in the hospital. Mbaluto said she had

Kala Azar, TB and meningitis.

Peter Garmaac Chol, a 37 year-old blind man from a village near the town

of Ayod, showed up at the hospital in January suffering from Kala Azar. He

travelled on his own for over two days, making his way to the hospital

despite his lack of sight.

Chol, who was 1.91 mt tall, but weighed only 53 kg, was discharged on 21

February, but he was still too weak to make the entire journey back to his

village by himself.

“We are trying to track down his relatives so that they can pick him up,

but so far we have been unsuccessful,” Mbaluto said.

Other Diseases Widespread

Diseases such as TB, malaria, diarrhoea, pneumonia and severe

malnutrition, have also taken a heavy toll on the population of Upper

Nile. During the last week of February, the Malakal hospital had 170 TB

patients on treatment.

“TB is endemic all year round and, as the first phase of the disease is

highly infectious, new patients have to be isolated for up to 2 months,”

Moussa Hamadan, a national TB doctor, told IRIN.

To complete the treatment, patients have to stay on combined TB drugs

treatment for six to nine months. Those who live far away stay in the

hospital during the entire time. Patients from nearby villages only stay

in quarantine during the initial phase, then come to the hospital to get

their medication every day.

MSF is training medical staff from the Sudanese Ministry of Health to

eventually take over the Kala Azar and TB programmes. However, it costs

almost US $1000 to treat a TB patient, which is a substantial financial

constraint for the ministry.

Food Shortages Make Matters Worse

Disease is rampant in Upper Nile, but lack of adequate food exacerbates

matters. The region experienced very late rainfall during the last

planting season and as a result, there was widespread crop failure.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

(OCHA), there was “strong evidence that there may be a region-wide food

security crisis that will push the existing, highly food insecure

population into an even more precarious situation”, later.

Around Malakal, the displacement of thousands of people from the nearby

Shilluk Kingdom by attacks from government-allied militias in 2004 created

further needs. An estimated 25,000 displaced Shilluk were still in Malakal

town in February, while thousands of others had sought refuge in nearby

towns.

A report by the US-sponsored Civilian Protection Monitoring Team (CPMT)

said residents who had remained in the villages had yet to recover from

the devastating effects of the fighting.

The region, the CPMT added, was facing severe food shortages as the

planting season had been disrupted by the armed conflict.

Adeng Anwour, team leader in Malakal for the Food and Agricultural

Organization, told IRIN on 25 February that the price of sorghum on the

local markets had gone up. While the supply had lowered, the demand had

gone up because of the displaced people.

“A 90-kg bag of sorghum is 10,000 Sudanese dinars [$40], but it was

6,000-7,000 Sudanese dinars [$24-$28] at the same time last year,” he

said. “It might go up to 15,000 Sudanese dinars [$60] in May, June and

July.”

He added: “During average years, there is a food gap between May, when

households’ food stocks are running out, and July, when the early maize

harvest comes in. This year people are already running out of food in

February.”

Ger Tervoort, MSF project coordinator, told IRIN: “We are seeing a high

number of severely malnourished patients, particularly among the children

admitted to the paediatric hospital and among Kala Azar admissions, and we

expect the admission rate to go up.

“The number of new admissions in our Therapeutic Feeding Centre was stable

at around 40 during December and January, but, since last week, the number

has started to go up,” he said on 24 February.

Patients With Families

The hospital, at times, has to cope with the relatives of the patients as

well.

A Nuer man called Simon had arrived in the hospital from Galla Hill

village, close to Nasir on the Ethiopian border, more than 200 km from

Malakal. Severely malnourished, he was diagnosed with Kala Azar.

However, Simon did not come alone. Outside the intensive care unit were

his wife and his three children, sitting in the shade.

“Having whole families here can be a real strain on our resources, but as

they are a long way from home, we cannot deny them food,” Mbaluto said.

He added that there was also a medical reason for feeding the patient’s

caretakers.

“In the past, we had cases where a patient’s recovery got slowed down as

he shared the hospital’s food rations with his relatives.”

According to nurse Liane Behrens, however, the large number of people that

were staying in and around the hospital for a prolonged period of time was

an opportunity, rather than a constraint.

“TB and Kala Azar patients and their care-takers, who stay here for

months, are an ideal target for our health education programme,” she told

IRIN. “We try to avoid the social stigma that is associated with TB

patients and teach them about HIV/AIDS, as well as preventive measures,

such as the use of mosquito nets, the importance of washing hands and

covering food.”

Future Needs Great

The Upper Nile region only recently opened up to international

organisations, following the signing of a comprehensive peace agreement

between the Sudan government and the southern Sudan People’s Liberation

Movement/Army (SPLM/A).

The agreement, signed in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, on 9 January,

officially ended 21 years of conflict between the government in Khartoum

and the SLPM/A, which said it was fighting to emancipate the southerners.

The region has very few clinics. Apart from the hospital in Malakal, MSF

has opened three basic health care units along the Sobat River, which runs

west from the Ethiopian border and reaches the Nile near Malakal.

“We continue to try to improve the access to treatment and expand our

mobile medical service in order to reach those most at risk,” Tervoort

said. “Already, we are seeing more cases of Kala Azar in the outreach

centres in Ulang and Nasir [along the Sobat River] than we are seeing in

the whole Kala Azar referral centre in Malakal.”

He added: “Our greatest problem, as well as for the Ministry of Health, is

to find trained staff – nurses, general medical technicians, and doctors.

University access for southerners had been extremely restricted, resulting

in a very limited number of available doctors.”

A report by the UN Children’s Fund, published in June 2004, estimated that

there was only one doctor per 100,000 people in southern Sudan.