Misery stalks southern Sudan despite peace deal

OLD FANGAK, Sudan, April 7 (AFP) — Though peace may have come to south Sudan, Nyanjun Chuol has been camping in this sun-scorched, poverty-stricken village with her husband and three children for four months awaiting medical care.

|

|

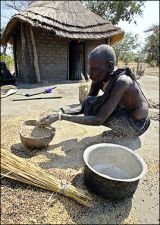

A woman in the southern Sudanese town of Rumbek cleans grain. (AFP). |

“We came here for treatment, but we have not yet received it,” says the middle-aged woman from neighboring Ayoti who, along with her family, suffers from a variety of undiagnosed ailments.

As temperatures in Old Fangak, a collection of grass-thatched huts most of whose occupants appear malnourished, soar to 40 degrees centigrade (104 degrees Fahrenheit) Choul expresses little hope that they will be seen any time soon.

The small clinic, run by the Italian relief group COSV is still under construction and has only one untrained medic.

Meanwhile, prospects for nourishment appear equally slim as their impoverished hosts struggle to feed themselves.

Food is scarce in Old Fangak, but the nearby River Zerati does offer some fish to the locals, mainly herders from the Nuer ethnic community.

At least 41,000 people living in Old Fangak, a sort of trading post, and outlying villages are facing food shortages. Food aid delivered thus far is only enough for 5,000, officials said.

The hardships here in Sudan’s oil-rich Upper Nile State mirror dilemmas faced throughout the south three months after Khartoum and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) signed a peace agreement that ended 21 years of conflict.

Only rusty shacks and ruined colonial buildings made of bricks stand out in most parts of southern Sudan. The other structures are all made of mud and reeds and there there are no roads or running water.

“We need assistance,” Isaac Gatkhor, an official with of the Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Commission, the SPLM/A’s humanitarian wing, told a group of reporters travelling with the German aid group Signs of Hope which supports education projects here.

“The peace should now go to the hearts of the people here in order to bring change,” said Reimund Reubelt, the head of Sign of Hope. “This is my hope and prayer.”

Next week, Norway will host representatives from international donors who are being asked to fund billions of dollars in post-war reconstruction and rehabilitation projects, much of it intended for the south.

Local leaders are anxiously hoping that at least some to filter down to Old Fangak but warn that time is running short.

Displaced people have started to return to their homes here from larger towns where they had fled the war, further straining resources in the village.

And around 160 people who fled militia attacks near the garrison town of Malakal last year to come to Old Fangak are reluctant to leave.

January’s peace agreement between Khartoum and the SPLM/A meant nothing to them, at least not for now.

“I will not return home,” said Veronica Arop. “I fear being attacked. We are not sure of the peace deal.”

As she spoke, several forlorn women stood by, clutching half-dressed babies appealing for assistance: aid that does not seem likely in the near future.

A week ago, a group of American surgeons visted Old Fangak, operating on about 150 people but follow-up visits are uncertain.

“There is no follow-up on their conditions,” said a Roman Catholic priest here.

Local medical treatment is far too expensive for most to afford. To get surgery in Malakal, locals have to part with two cows for operation and one for medicine.