FEATURE-Sudan fears to loose political control of Darfur

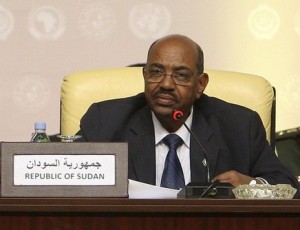

Oct 9, 2006 (KHARTOUM) — Sudanese president is fighting hard to keep U.N. peacekeepers out of Darfur by accusing western “crusaders” of trying to take over the country. But what he really fears may be more more basic: Losing control over a key political stronghold in the troubled region.

That determination to keep tight control of Darfur and prevent any loosening of his regime’s grip on the large, sprawling country overall could complicate the West’s efforts to help Darfur’s suffering millions, observers say.

That determination to keep tight control of Darfur and prevent any loosening of his regime’s grip on the large, sprawling country overall could complicate the West’s efforts to help Darfur’s suffering millions, observers say.

The United Nations, United States, Europe and African nations insist they have no hidden agenda and merely want to help get humanitarian aid to Darfur. They believe only a strong U.N. peacekeeping force can end the violence in the western region, where more than 200,000 people have been killed and 2.5 million chased from their homes in fighting between rebels and the army.

But Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir has warned he would personally lead a jihad, or holy war, against any U.N. troops.

And Khartoum has continuously sought to feed into widespread conspiracy theories of a western “crusade” against Arab countries, pointing to the invasion of Iraq and the killing of Lebanese civilians by Israel as proof that the U.N. is biased against Arabs.

Khartoum also claims the mounting American outcry over Darfur is fueled by “Zionist groups” and says that charities hype the crisis for political gain.

“I don’t think diplomatic pressure of any kind will make Khartoum accept a U.N. peacekeeping mission,” said Suleiman Baldo, a Sudan expert at the U.S.-based International Crisis Group.

The issue was throw into stark relief recently when, on a visit to Cairo, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice spent much of her time with Arab officials lobbying them to intercede with Sudan, rather than on Arab-Israeli peace efforts or the Lebanon war.

Despite such high-profile efforts, the West has been unable to persuade Sudan that its intentions are purely humanitarian. Sudan has refused to consider allowing a U.S. peackeeping force now in the south to move to Darfur in the west, or to allow the United Nations to take over a current, feeble Darfur peacekeeping mission by the Africa Union.

It also recently rejected an Arab League overture to allow Arab peacekeepers, although Arab diplomats said al-Bashir promised to offer a counterproposal.

Al-Bashir did send a letter to U.S. Secretary General Kofi Annan last week reiterating that he would consent to the U.N. providing support to the AU mission.

Supporters of a U.N. force have tried to point out that both victims and perpetrators in Darfur are in many cases Muslims, although pro-government Arab militias are accused of most atrocities against ethnic African villagers.

They also point out that the sprawling, landlocked desert region would be of little strategic value to anybody.

But, “there is no trust left,” says Majzoub al-Khalifa, Sudan’s top official for Darfur. “How can the international community guarantee that America will not use the U.N. to turn Sudan into a new Iraq?”

Sudanese contend that rumored oil and uranium fields under Darfur, and even Pope Benedict XVI’s recent comments on Islam, are the real reasons the West wants to move in.

Such arguments probably hold some weight in a part of the world where Arabs have high mistrust of American motives.

But the top U.S. diplomat in Sudan dismisses them. “I have constant conversations with (Sudanese officials). They never talk to me about a hidden agenda,” Cameron Hume said.

Indeed, the harsh rhetoric has come even as the Sudanese regime has collaborated with the Bush administration on terror issues. But it has a weak spot in the rebellions that often break out across its vast expanse.

“The fact is that the government isn’t going toward more democracy, and rebellions across the country reflect this,” said El-Tayeb Ateya, who heads the Peace Institute at Khartoum’s university.

Darfur, though underdeveloped, has long been a power base for Khartoum political parties — unlike the largely Christian south, where Sudan agreed to U.N. peacekeepers as part of a 2005 peace treaty.

Meanwhile, a third revolt in the east could evolve into the next humanitarian crisis. But Khartoum says it will soon reach a peace deal with eastern rebels there.

And it has shown itself anxious to not let the separate clashes be merged into one countrywide problem that the West feels it must address.

(AP/ST)